I’m sitting in a crowded conference room at Marin County Department of Health and Human Services, watching as these chilling messages flash by on the screen: Each year, 44,965 Americans die by suicide. For every recorded suicide, 25 people attempt and survive. In the U.S., suicide kills more people than homicide, war and natural disaster combined.

Around me are health professionals and advocates, educators, concerned citizens and family members of those who have died by suicide. Their faces reflect shock, sorrow, and concern as they take notes, ask questions and murmur to those around them.

“This topic is very frightening to people,” says Ryan Ayers, Northern California area director for the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention. “But it’s important to have these conversations because that’s how we save lives.” Indeed, the title of Ayers’ presentation is “Talk Saves Lives,” and this is the third time this week he has delivered it to a Marin audience as part of a comprehensive program of suicide prevention awareness taking place around the county this fall and winter.

There’s good reason for Marin’s public health and academic communities to be focused on suicide right now. While by most health measures Marin is among the healthiest counties in the state, when it comes to suicide it’s another story. As of 2016, the last year for which statewide data is available, Marin had the highest suicide rate of any county in the Bay Area, exceeded only by a small number of the state’s most rural and isolated counties, long at the greatest risk.

“Marin has been rated the healthiest county in the state for eight years, and also the wealthiest, and yet at the same time, we have higher rates of death by suicide than other counties that measure much lower on these other scales,” says Matt Willis, Marin County’s chief public health officer.

In 2017 there were 42 deaths by suicide in Marin, and data for 2018 tallied up to the end of September showed 21 suicides, with several additional deaths still under investigation. In 2016, Marin had 47 suicide deaths, a notable rise from 2015, which saw 30. Those deaths crossed all age groups and walks of life, from teens to those in their 80s, with the great majority in the midlife years. But perhaps the number that rang the loudest alarm came last winter, when three Marin teenagers died by suicide in a one-month period.

“In Marin, losing three young people in so short a time was a real wake-up call,” Willis says. “We already have a lot of support services in place, but we realized we needed to have a bigger conversation and find a way to bring all of that together into a cohesive and holistic approach and get everyone working together to bring this to public attention.”

Suicide affects not just those who were close to the person who died, but the whole community, says former Marin County coroner Ken Holmes, whose 36-year career was documented in John Bateson’s The Education of a Coroner: Lessons in Investigating Death. “The ripples in the pond of suicide go in so many directions, and all those people ask themselves if there is something they could have or should have done. Those who lose loved ones this way take it on their shoulders for years and years.”

Nationally, suicide rates have been climbing steadily since 1999, and California saw an increase of nearly 15 percent between 1996 and 2016. Data from 2014 to 2016 tallied by Healthy Marin show that Marin’s rate of death by suicide is 12.2 per 100,000, as compared with a rate of 10.4 across California.

Meanwhile, high-profile suicides such as those of designer Kate Spade and chef Anthony Bourdain this summer and Marin’s own Robin Williams in 2014 have brought unprecedented attention to the issue.

“This has been a hidden problem for too long, and the community is acknowledging that we need to do some soul-searching,” Willis says. “Part of the story here is that until now, people didn’t know that we had higher suicide rates than most counties. There is so much stigma that it doesn’t even get reported or talked about and most people don’t even hear when someone dies this way.”

It Could be Anyone

The stories behind Marin’s suicide statistics are many and varied. But if there’s one theme that runs through all, it’s that there is no simple explanation of what brought someone to this point.

“When you suffer a loss unexpectedly like this it terrifies people, so it’s natural to try to grapple with the why,” says Penelope Draganic, whose husband Zarko died by suicide in 2014 at age 47. “People look for a terrible life event they can point to, something that happened externally that made the person no longer value their life. But the most important piece to understand is that when someone kills themself, their mind isn’t working well.”

Certainly Zarko Draganic seemed the epitome of success; a groundbreaking and influential technology entrepreneur, he founded and sold companies, raced sailboats, and lived with his wife and two children in a beautiful Belvedere home. “My husband was loved, he had a beautiful family and wonderful friends, he was an engaged member of the community and brilliant contributor to society,” Penelope Draganic says.

Her husband battled depression, struggling to treat it with medications that caused additional complications. But his suicide was sudden, impulsive and unplanned — there were no previous signs or attempts and he never communicated a desire to harm himself to his wife or those treating his depression.

“The disease creates a negative thinking loop pattern, and the thoughts aren’t true, but the individual who is suffering believes them,” she says. “And in that belief system the distorted narrative is so gripping that he can feel completely overwhelmed and may act compulsively to escape the excruciating psychological pain.”

When you listen to Draganic’s story and those of other survivors, one thing becomes very clear: we search for causes because we want something that separates us from these experiences. But the more stories you hear, the harder it becomes to hold on to the idea that this couldn’t happen to those we love, or to us.

Shattering the Stigma

Since her husband’s death, Penelope Draganic has worked to reduce the shame, fear and silence surrounding mental illness, becoming a counselor and coach and joining the board of Bring Change to Mind, an organization founded by actress Glenn Close in 2010 after Close’s sister Jessie was diagnosed with bipolar disorder and her nephew with schizoaffective disorder.

“What I’ve learned since Zarko’s death is that being direct about this stuff is really, really important,” Draganic says. “Research has shown when people strip away stigma and have courageous conversations about mental illness with their community, their circle of family and friends, they are much better equipped to cope with what they’re experiencing than when they are isolated, afraid and ashamed.”

Suicide experts agree, saying that one of the biggest misconceptions about suicide is that discussing it might lead someone to take their own life. “We used to think that talking about it might plant a seed, but we’ve come 180 degrees from that thinking,” Ayers says. “If someone is suicidal, asking them about it is not going to push them closer to the edge, and if someone isn’t suicidal, asking if they’re at risk isn’t going to put the idea in their head.”

Many also fail to understand just how sudden — and short-lived — the impulse can be. “In one study, when psychologists and ER personnel interviewed survivors of suicide attempts, they described shockingly short time periods between deciding to die and making an attempt,” says Susan Acker, assistant director of Suicide Prevention and Community Counseling for Buckelew Programs, which staffs and runs the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline for the North Bay. “Nearly 25 percent took less than five minutes and most of the rest took less than an hour.”

For this reason it’s important to reach out when a loved one hits a rough patch, Acker says. “Rather than waiting for signs, we can stop more suicide deaths by leaning in when friends and family lose jobs or relationships or housing or have legal and financial problems or are under work or school stress,” she says. “Learn how to ask. It won’t make it worse.”

Conversations about suicide are starting to happen in many walks of life. In September, the California Fire Service asked all firefighting personnel to participate in a behavioral health and suicide awareness stand-down, to reveal and explore the high suicide risk among firefighters.

The numbers they shared: last year, more firefighters died from suicide than from being on duty. In the summer of 2018, three California firefighters took their own lives. And national surveys show that one in three firefighters has considered suicide. The message on the flyer: “The first step in breaking the stigma is to start talking.”

Progress is being made — five years ago, just one in five people with a mental health condition sought treatment, and today that percentage has doubled to two in five. But that still leaves more than half of those suffering without help.

At the same time that experts spread awareness about the preventability of suicide, though, they caution that this doesn’t mean those left behind should blame themselves or feel in any way at fault that they weren’t able to intervene.

“While we have to approach this believing that suicides are preventable, suicide also needs to be seen in the wider frame of public health, and how we hold one another in healthy communities,” says county health officer Willis. “We need to be careful not to assume that responsibility falls on families, friends and health care providers of victims. Prevention is shared by all of us.”

Seeing the Bigger Picture

Nowhere is that connection more clear than in Marin’s low-income and immigrant communities. “What we’re seeing among our patients is rising rates of stress because of the sociopolitical context and economic factors,” says Elizabeth Horevitz, director of behavioral health at Marin Community Clinics.

“Specifically with regard to our immigrant population, when you have multiple families living in one room under terrible conditions and living in fear of being sent back [to their home countries] and killed by a gang, those are tremendous mental health pressures,” Horevitz says. “It feels like a perfect storm that puts people even more at risk. Hopelessness and helplessness are predictors of depression and suicide, and when people are faced with the prospect of deportation, we are reinforcing hopelessness and helplessness on a broad scale.”

Calls to the suicide lifeline reflect these stressors too, Acker says. “We are hearing from more elders and others on fixed or low incomes being displaced by sudden evictions as rents go up, and the fires in the North Bay continue to cause grief, anxiety, loss and hopelessness. Drugs and alcohol and financial pressures are also big contributing factors.”

Marin has a higher proportion of residents over age 65 than any other Bay Area county, and their struggles are reflected in the suicide rate as well. “Suicide in older adults is often a symptom of social isolation, especially after the death of a spouse and when children are grown and gone,” Willis says.

Protecting Youth

Suicide is now the second leading cause of death for people ages 15 to 34, second only to accidents, national statistics show. And 16- to 25-year-olds are the predominant age group among new callers to the suicide lifeline, according to Buckelew Programs. Almost every year, at least one Marin County teenager dies by suicide; in addition to the three teens last winter, there were four more such deaths among young people age 10 to 19 between 2013 and 2017.

Behind these numbers are deeply concerning statistics on attempted suicide and suicidal ideation (thoughts or plans) among teens. A 2015 nationwide survey by Kidsdata, a project of the Lucile Packard Foundation for Children’s Health, found that more than one in six high school students said they had attempted suicide in the previous year, and more than one in 12 reported such an attempt.

While men and boys of all ages are more likely to die by suicide, data from the state of California collected between 2013 and 2015 show that high school girls are more likely to say they think about ending their lives. Almost 22 percent of ninth-grade girls and almost 20 percent of 11thgrade girls said yes to a question about suicidal ideation. By contrast, just 9 percent of ninth-grade boys and 15 percent of 11th-grade boys said they’d had suicidal thoughts.

Data show that suicide rates are rising faster among certain groups of young people, particularly Hispanic teenage girls. In 2012 the Centers for Disease Control issued a report that 13.5 percent of Hispanic girls ages 14–18 had attempted suicide, a considerably higher percentage than girls from any other ethnic group.

In recent years, there has been a deeper understanding of the ways in which news of one death by suicide can lead to others, particularly among the young. While the underlying reasons and factors are complex and not fully understood, the facts are clear: when one death by suicide comes vividly to a community’s attention, the chances of another increase.

That doesn’t mean we shouldn’t talk about suicide — it’s important that we do. But the way such deaths are handled in communities and how they’re covered in the media can contribute to contagion. This concern is reflected in new crisis response protocols announced this fall as the result of a collaboration between the Marin County Office of Education, Kaiser Permanente, and Marin County Health and Human Services. The protocols set out guidelines for short- and long-term response in the event of the death of a student by suicide or otherwise, providing tools to help schools communicate with parents and students and offering coping methods and resources.

“Given how much time kids spend at school, we want to make sure our schools are supporting the whole child, not just the academic side, and that we’re providing educators with the communications strategies and other tools they need,” says Jonathan Lenz, Marin County’s assistant superintendent for special education.

California also passed a new state law, Assembly Bill 2246, that requires every school district that serves students grades seven to 12 to have a board-approved suicide prevention policy in place. While AB 2246 doesn’t cover grades six and below and private schools, the state department of education urges all schools to adopt suicide prevention policies “as safety nets for all students.”

Throughout the fall, Marin’s school districts held video screenings and alertness trainings to educate students, parents and teachers on how to watch for signs of suicide risk and intervene when someone is at risk. And on November 17, National Survivor Day, the district and the county office of education co-hosted an education event in collaboration with the American Federation for Suicide Prevention

A Slow Tide of Change

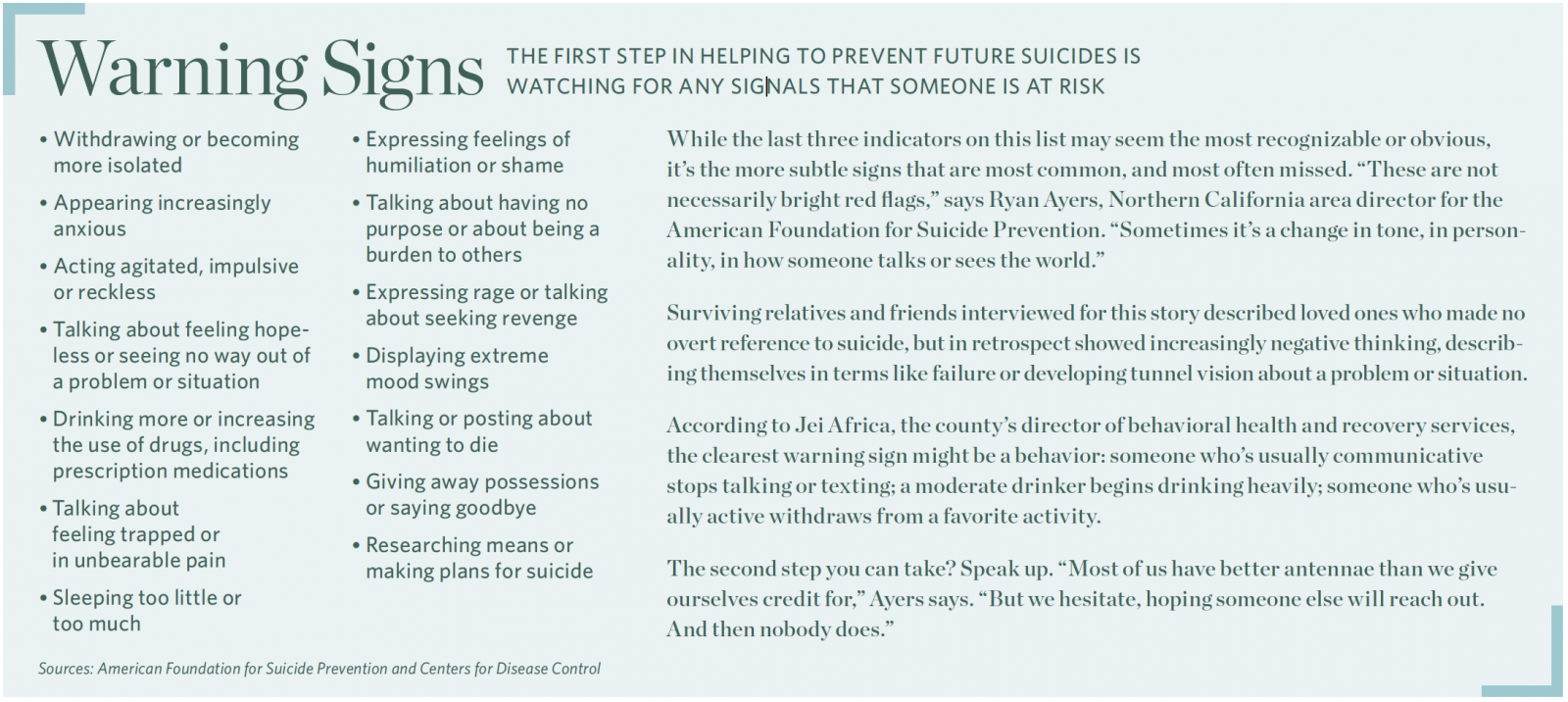

The school-based efforts are just part of a multipronged effort underway this year to bring suicide to the forefront as a major public health issue and give county residents the tools to spot the warning signs of suicide and intervene to prevent it.

This fall, the Marin County Board of Supervisors issued an unprecedented call to action, proclaiming September to be National Recovery Month. Announcing that an estimated 50,000 county residents are affected by mental health and substance use issues, the resolution encourages relatives, friends and the entire community to watch for signs that someone is struggling and speak up to offer concern, support and resources.

Marin Community Clinics have launched the Zero Suicide Initiative, part of a health care movement to screen every patient for suicidal thinking and behavior. “More than 50 percent of adults who attempt suicide have seen their medical provider in primary care within the last month,” Horevitz says.

“Patients are being seen by someone who could make a difference, and yet the data show we’re not catching it in primary care. Historically, this is not something that’s checked in the same way that we check blood pressure, but it absolutely should be.”

The county has beefed up mental health response with a new mobile crisis response team and a 24-hour stabilization unit available to respond with immediate mental health help, says Jei Africa, director of behavioral health and recovery services for Marin’s Department of Health and Human Services “There needs to be a full spectrum of services to provide a safety net at every stage.” Among the many resources available to older adults are a senior peer counseling program that pairs volunteers with older adults in need of support and the Marin Villages program, which helps older adults connect through local “village” networks. “Suicide can’t just be a school issue, and it can’t just be behavioral and mental health issue; it needs to be a community issue,” says Lenz. “We need to get everybody around the table, working off the same plan, acting out of the same beliefs, and speaking the same language.”

Perhaps the clearest evidence of change was on display this fall at showings of the film Not Alone, which grew out of Marin County resident Jacqueline Monetta’s experience of losing her best friend to suicide when she was a sophomore in high school.

“I didn’t know what to feel — I was shocked and sad and mad and I felt constantly guilty, wondering if I could have done something,” Monetta recalls. And then it happened again, and again.

“I personally knew six teens who died by suicide in my four years of high school, all from the Bay Area and several from Marin,” Monetta says. “And each time those feelings came back and I started to look around for answers: Why is this happening? What’s going on in this community that teens are feeling like this?”

Searching for understanding and insight, Monetta realized she didn’t want to hear theories and explanations from experts and adults — she wanted to hear from teens themselves. So she started interviewing them.

The result is a moving documentary co-directed with Marin filmmaker and producer Kiki Goshay in which teens speak with remarkable honesty about their own experiences with depression, suicide, cutting and other mental health issues — and what got them through the dark times.

Since the film premiered at the Mill Valley Film Festival in 2017, community groups and schools around the North Bay have hosted screenings, using the film as the jumping-off point to create openness and conversation about teen mental health.

“The positive message is that all these teens survived and found their way to a better place by opening up and telling a friend, a parent, a counselor, and became stronger by sharing their stories with each other,” says Goshay, who is also on the board of the Green Light Clinic, a mental health clinic in San Francisco offering free confidential counseling and treatment to teens.

Now available on Netflix, Not Alone is finding a wide audience, and it’s been extremely gratifying to see the message spread, says Monetta, who now works for a talent agency in Los Angeles and plans to become a filmmaker.

“I get at least 10 messages a day via Facebook, Instagram and text from young people all over the world reaching out to talk about what a big issue this is for them and telling me how the film has helped them reach out to friends and others around them,” she says.

“All I wanted was to help others so they wouldn’t have to go through what I went through losing my best friend,” she says. “It’s been wonderful to see the response, but it also shows that there’s still so much work to do.”

Resources

NATIONAL SUICIDE PREVENTION LIFELINE

800.273.8255

Text HOME to 741741

AMERICAN FOUNDATION FOR SUICIDE PREVENTION

KNOW THE SIGNS: STATEWIDE SUICIDE PREVENTION CAMPAIGN

free mental health clinic for teens

NATIONAL ALLIANCE ON MENTAL ILLNESS

California,

founded by Glenn Close

Melanie Haiken is a writer, editor and web project manager based in the San Francisco Bay Area. She operates on two simple assumptions: Everyone has a story to tell. And a story well-told will always find an audience. Her work is characterized by exceptional clarity, depth and insight – no matter the topic covered. Haiken writes for AFAR, Forbes, Via, Yoga Journal and many other national magazines and websites. She has also created award-winning marketing and custom publishing materials and communications campaigns for clients like Adobe, Wells Fargo, Lane Bryant, Kaiser Permanente and Safeway.