For shelter from the scorching midday sun, I am leaning in the shadow of a destroyed Russian tank. The number 124 is stenciled on its side. I am just inside the Afghanistan border after crossing from Tajikistan—no-man’s-land—and “Comfortably Numb,” one of my favorite songs from Pink Floyd’s The Wall, is playing in my head. The hot metal from the tank feels like an oven on my back, but I am content, happy actually. This is what adventure travel should be.

My guide is not here yet. Passersby, some carrying household goods, others guns, stare at me. No doubt they are wondering why I am here. I contemplate the question of how this tank, and another one next to it, ended up here. What happened to the crew? I’m sure it was not pleasant. Did they die fighting? Were they taken prisoner? The line between life and death is easily crossed in these parts of the world.

Men wearing dismaals, the traditional Afghani scarves, ask me questions I do not understand. They do not seem threatening and I have traveled enough in strange places that I know eventually someone will show up and everything will work out. At the least, when darkness comes the military will want to make sure they know what I am doing. For a microsecond, though, the thought crosses my mind: why don’t I just vacation in Hawaii like most people? But it passes. I love being here in the middle of the nowhere, all alone, leaning against a tank. This is bliss.

Men wearing dismaals, the traditional Afghani scarves, ask me questions I do not understand. They do not seem threatening and I have traveled enough in strange places that I know eventually someone will show up and everything will work out. At the least, when darkness comes the military will want to make sure they know what I am doing. For a microsecond, though, the thought crosses my mind: why don’t I just vacation in Hawaii like most people? But it passes. I love being here in the middle of the nowhere, all alone, leaning against a tank. This is bliss.

My journey started in Mill Valley, then continued via Frankfurt to Istanbul and Dushanbe, the capital of Tajikistan, where the whole trip almost collapsed because Tajik authorities said my visa was not correct and it would take two weeks to “fix it.” Time was something I did not have. I was here for a short trek in Afghanistan’s Wakhan corridor and had to get back in a few days, so after the U.S. embassy told me it couldn’t help I spent two long days maneuvering through the Tajik bureaucracy in ways that would have made Agatha Christie proud (no murders were involved) and I was able to get my visa “corrected.”

The drive from Dushanbe into Afghanistan took nearly three days, much of it over bone-jarring roads. At the guesthouses en route, my choices for evening companions were rats, white scorpions (“they will not hurt you much,” said one innkeeper) or, if I slept outside, mosquitoes. I had been softened in recent years by five-star tent camping in Africa and hotels in India with showers and had forgotten what a real adventure was like. This trip restored that memory.

My guide finally arrives

I see someone running toward me shaking his hands—my very apologetic guide. Our first stop is a return visit to the Afghani immigration office because the official there had not, my guide pointed out, stamped my passport. Papers in order, we drive toward Ishkashim, the capital of a province in eastern Afghanistan of the same name. On the road, I see plenty of minibuses with a photo of Ahmad Shah Massoud on their windshields. He was the commander of the anti-Taliban Northern Alliance who was killed by a suicide bomber a few days before 9/11. He is a hero here and locals say his name with respect in their eyes and voices. They call him Amer Sahib e Shaheed, “our martyred commander.”

In Ishkashim, I must register with the local police. The police station looks like a fort, but the commander is friendly and insists I sit with him for tea and a chat. I see two old army vehicles, an anti-aircraft truck hidden under a tree and a rocket-launching truck parked with flat tires. May I take photos, I ask? No, says the commander. Later, though, after a couple cups of tea he tells me I can take all the photos I want. I love Asia!

In Ishkashim, I must register with the local police. The police station looks like a fort, but the commander is friendly and insists I sit with him for tea and a chat. I see two old army vehicles, an anti-aircraft truck hidden under a tree and a rocket-launching truck parked with flat tires. May I take photos, I ask? No, says the commander. Later, though, after a couple cups of tea he tells me I can take all the photos I want. I love Asia!

The next morning we drive east toward China and after an hour the valley opens up to an incredible view of the surrounding mountains. The “road’’—and to call it that is a stretch—is extremely rough, dusty and slow going. As we go by, villagers wave and call out al salaam a’alaykum (“peace upon you”) and touch their hearts with their right hands as a sign of respect.

During the day we cross, recross and cross again the Oxus River, with the water at times halfway up the SUV doors. It takes nine hours to drive about 70 miles. We follow the riverbed, climbing slowly and bracketed by spectacular mountains—the Hindu Kush to the right, the Pamirs to the left. We reach an Afghani military post, where we wait for hours for the senior officer to arrive. I settle back to take in the scenery, knowing that like so many things in Asia, this will work itself out. And it does. After some small talk, apologies and a cup of tea, we are back on our way.

Soon, we actually cross a bridge, the only one we’ve seen so far in the area. An hour later we arrive at a village consisting of three mud homes. Immediately, the villagers come out, smiling and greeting me with hugs like I am a long-lost friend. They give me the best room in the house to spend the night in and while I am stowing my duffel bag there I hear a chicken scream its last scream. I know what dinner is going to be. We all eat together and I am asked to eat more and more even though I’m full—how can I say no to these smiling faces? Outside, the moon is nearly full. The bright lunar light mixes with a soft breeze coming down the valley, stirring the tips of the unharvested wheat. I’m reminded of being at sea.

Soon, we actually cross a bridge, the only one we’ve seen so far in the area. An hour later we arrive at a village consisting of three mud homes. Immediately, the villagers come out, smiling and greeting me with hugs like I am a long-lost friend. They give me the best room in the house to spend the night in and while I am stowing my duffel bag there I hear a chicken scream its last scream. I know what dinner is going to be. We all eat together and I am asked to eat more and more even though I’m full—how can I say no to these smiling faces? Outside, the moon is nearly full. The bright lunar light mixes with a soft breeze coming down the valley, stirring the tips of the unharvested wheat. I’m reminded of being at sea.

The next day we drive only three hours, but it is all very rough. Our destination is Sarhad, another small village, where I spend the night before starting my trek. I am a very seasoned Himalayan trekker, having done some of the most exotic treks—Dolpo, Snow Lake, K-2 and Kangshung Face. Though this trip’s trek is not rigorous by Himalayan standards, it is one of the most rewarding because of the people and the peaceful scenery.

On the first day of the trek, we stop to rest at about 13,800 feet. Behind me is the small hill we walked up; ahead and to the sides are three distinct mountain ranges—the Karakoram on the left, the Hindu Kush in the center and the Pamirs on the right. That night the moon is full, lighting up the landscape brilliantly. I spend hours on a rock taking it all in and thinking how fortunate I am to be able to experience wondrous places such as this.

What’s for dinner?

“Shall I kill a goat or a sheep for you? Which one do you like best?” the owner of the guesthouse says. I have just finished the trek and after the requisite hugs and greetings he announces that as I am his honored guest — and one from Greece at that (Alexander’s legendary status is still alive up here) — he will kill a sheep or a goat. It’s my choice. I plead with him not to kill any animal, but he insists. Finally, I tell him it’s my birthday (true) and as a gift I want to spare the creature’s life. He agrees, but also says he needs to do something special anyway. A few minutes later the sound of two chickens in great distress fills the courtyard. At least it’s not a sheep, I think.

We spend the evening eating, drinking lots of tea and talking. After a discussion about history and the mythic feats of Alexander and Marco Polo, the conversation comes to the inevitable—the United States in Afghanistan, the Taliban and the future. The stories I hear this evening about the Taliban’s treatment of people in Kabul and other major cities keep me awake most of the night. I think of the eeriness of how they were told, the storyteller’s voice dropping nearly to a whisper, the tone low and serious. It is one of those conversations that you do not want to hear more of but feel compelled to listen to nonetheless. I can’t sleep, so I go outside the small mud home, sit on a rock and try to understand what seems so unfathomable. Another verse from Pink Floyd surfaces in my head: The flames are all gone but the pain lingers on.

The next day, back in the car, we come upon a police checkpoint. The officials are quite upset about something and they take all the gear out of the car, looking at everything and emptying my duffel on the ground. Then it’s over. They apologize profusely and tell me that last night one of their soldiers got drunk and lost his Kalashnikov and they are looking for it. They tell me he’s imprisoned for the slip-up. I drive off thinking he’ll probably be there for quite a while.

Three days later I am in Dushanbe again, heading home. Like always after this kind of trip, I feel different, changed ever so slightly, but nonetheless irrevocably, by experiencing one of the world’s last true adventures.

Image 2: Villagers pass by carrying household goods.

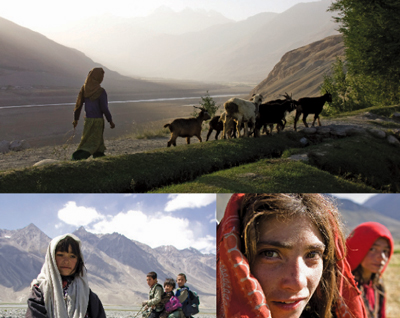

Image 3: Sunrise at the Wakhan. The young girl takes the goats out to the fields with the Hindu Kush in the background.

Image 4: Going to school is something new for girls in Afghanistan after years of Taliban rule.

Image 5: Young Wakhi girls taking a rest from the harvesting to get a look at the foreigner.

Image 6: Wakhi mother and her child leave their home.

Image 7: (left) Sarhad and the start of the trek with view of majestic Pakistan mountains in the background.

Geographic Expeditions will be offering a trekking tour of the Wakhan corridor in Afghanistan in 2008. For more information visit geoex.com

To view more photos from Vassi Koutsaftis's travels, visit arclight-pictures.com.