PITCAIRN ISLAND. THE name alone may not ring any bells, but perhaps the HMS Bounty will. Fletcher Christian’s 1789 uprising against Lieutenant William Bligh on that vessel inspired Charles Nordhoff’s and James Norman Hall’s 1932 novel Mutiny on the Bounty, several movies, and even a musical. Marlon Brando played Christian in the 1962 film, and the star-studded cast of 1984’s The Bounty featured Anthony Hopkins as William Bligh, Daniel Day Lewis as John Fryer, Laurence Olivier as Admiral Hood, Liam Neeson as seaman Charles Churchill and a young Mel Gibson as Christian.

The remote volcanic island, located about 1,350 miles southeast of Tahiti, was named after British midshipman Robert Pitcairn, who was the first person to spot it on July 2, 1767. Two decades later, after overthrowing Bligh, Christian sailed to Tahiti, where 16 out of the 25 sailors and mutineers decided to stay. The remaining eight crewmen, their Tahitian women, several Tahitian men, and Christian sailed forth before settling on Pitcairn on January 23, 1790. The island’s location had been charted inaccurately, making it an attractive hideaway option, and a British ship searched for the rogue crew for three months to no avail. The mutineers who stayed on Tahiti didn’t fare as well — they were captured and brought back to England, and some were later hanged. The Pitcairn settlers weren’t discovered until 1808, but by that time they were only survived by mutineer John Adams. The majority were killed by either each other or the Tahitians who accompanied them; Adams wasn’t prosecuted and the descendants of the original group continue to live on the island.

Tony Probst is an avid maritime collector and owner of San Rafael’s Audio Video Integration. His interest in the Bounty and Pitcairn Island dates back to age 7, when he and his family left England for a 14-year sailing trip around the world. For entertainment, his father provided him with two books: Mutiny on the Bounty and Men Against the Sea. The stories resonated with young Probst, and though the family didn’t make it to Pitcairn, he decided that one day he would. In January 2010, he made his first visit. In a series of subsequent trips, Probst formed bonds with inhabitants of the island, gaining unprecedented access to artifacts, family stories and other uncommon information about the world’s most isolated place. The ties he developed were so deep, in fact, that he’s been entrusted with Christian family relics throughout the years. His photographs document these visits.

Look through these photos of Pitcairn Island to learn more about its history.

The earliest photo of Pitcairn Island in 1916 (top) and one almost 100 years later in 2012 (bottom).

A never-before-published 1898 photo of Thursday October Christian II, grandson of Fletcher Christian and son of Thursday October Christian I. Fletcher Christian didn’t want his son to bear an English name, hence this unusual one based on his birth date. There was a snag, however. The Bounty crossed the International Date Line, meaning Thursday’s name should have been Friday, which is the way he is identified on a Pitcairn Island stamp.

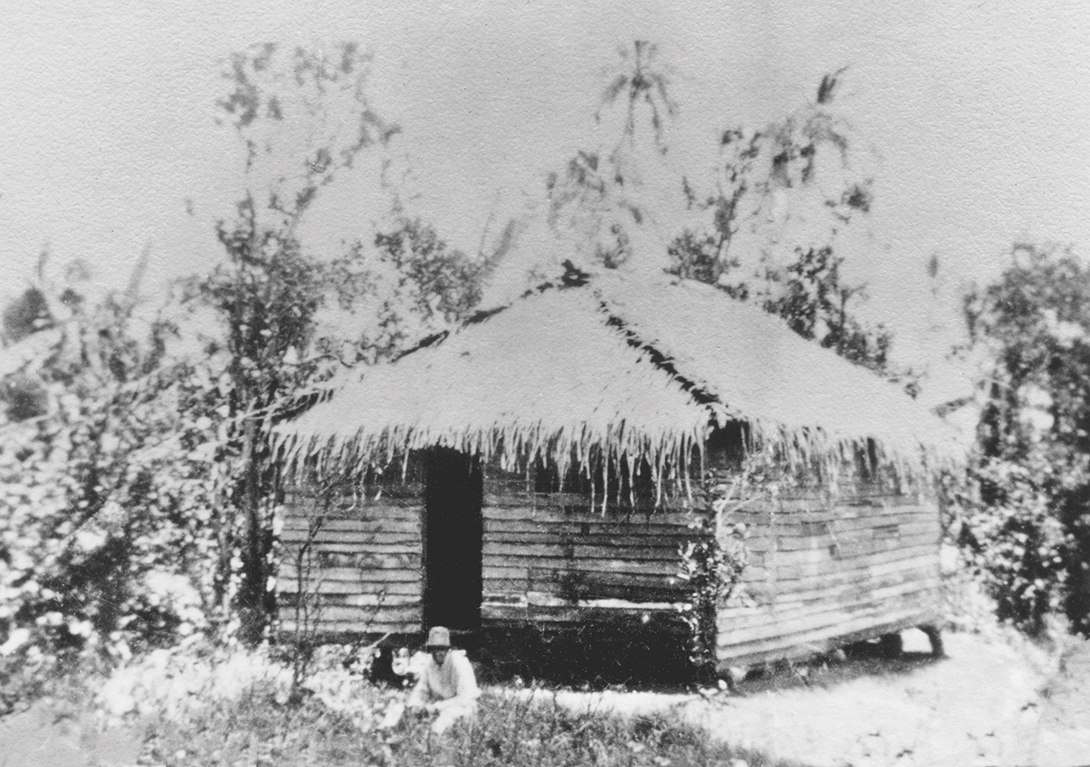

Thursday October Christian II, estimated to be around 90 in this photo, in front of his house in 1899. The diminutive isle (two by one mile) is the only Pitcairn Island of the four with fresh water. Despite modernization, electricity is limited in present-day Pitcairn and provided by diesel generators.

A longboat called the Barge in 1946. Pitcairn relies on shipping for survival, as everything not produced on the island comes by sea and is then brought ashore. The residents built their own wood boats up until 1983 and the last was retired in 1995.

A longboat called the Barge in 1946. Pitcairn relies on shipping for survival, as everything not produced on the island comes by sea and is then brought ashore. The residents built their own wood boats up until 1983 and the last was retired in 1995.

There are currently two aluminum boats being used that were built to the islanders’ specifications in New Zealand, named Tub and Moss. The island population peaked at 233 back in 1937 and now hovers at around 50.

Christian’s cave. It is said that this is where the lead mutineer watched for approaching ships and hid from the other settlers when he needed to.

The Landing and Bounty Bay — where the HMS Bounty lies — from the Small Edge. The mutineers burned and sank the ship (there was no other place to hide it) and founded a village. John Adams was the last surviving settler; he converted the women and children to Christianity. They lived this way for 24 years before being rediscovered by the British, who allowed the community to continue.

Bounty Bay and the large pinnacle outcropping known as Ships Landing Point. In 1838, Pitcairn became the first British colonial island in the Pacific and is now the only staunch reminder of the Royal Navy’s reign in that region. The water around Pitcairn, among the cleanest in the world, is about 70 feet deep in this photo.

The Gods formation as seen from the sea. In March of this year the British government announced plans to create the world’s largest fully protected marine reserve around the Pitcairn Islands — an area that is roughly 3.5 times the size of the United Kingdom (322,138 square miles). The reserve is home to more than 1,000 species of marine mammals, seabirds and fish.

Down Rope, a cliff on the southeast edge of the island, with ancient Polynesian petroglyphs carved in its face. Stone gods, earth ovens and other artifacts found in the area point to Polynesian settlement.

St. Paul’s Pool is a great place to learn to swim. This pristine tidal pool located on the eastern side of the island is a gorgeous natural attraction teeming with marine life. The National Geographic reporters who visited the island in 2012 dubbed the swimming hole their favorite.

This article originally appeared in Marin Magazine’s print edition with the headline: “Pitcairn Island”.

Kasia Pawlowska loves words. A native of Poland, Kasia moved to the States when she was seven. The San Francisco State University creative writing graduate went on to write for publications like the San Francisco Bay Guardian and KQED Arts among others prior to joining the Marin Magazine staff. Topics Kasia has covered include travel, trends, mushroom hunting, an award-winning series on social media addiction and loads of other random things. When she’s not busy blogging or researching and writing articles, she’s either at home writing postcards and reading or going to shows. Recently, Kasia has been trying to branch out and diversify, ie: use different emojis. Her quest for the perfect chip is never-ending.