This December, millions of moviegoers will line up outside multiplexes from Paris to Perth to see the seventh episode in the Star Wars saga. The Force Awakens will continue the adventures of Leia and Luke, Han and Chewie, Darth Vader and Boba Fett — mythological heroes and villains from the mind of San Rafael resident George Lucas, characters who have inspired our cultural consciousness the way Zeus and Medusa figured into yesteryear’s storytelling circles.

This December, millions of moviegoers will line up outside multiplexes from Paris to Perth to see the seventh episode in the Star Wars saga. The Force Awakens will continue the adventures of Leia and Luke, Han and Chewie, Darth Vader and Boba Fett — mythological heroes and villains from the mind of San Rafael resident George Lucas, characters who have inspired our cultural consciousness the way Zeus and Medusa figured into yesteryear’s storytelling circles.

Despite Lucas’ phenomenal success and unquestionable influence in the medium of film, it’s not difficult to imagine an alternate universe in which Star Wars does not exist. Lucas, raised in Modesto, was an extremely shy child who did not instantly gravitate toward film the way his contemporary Steven Spielberg did. As a teenager, he was passionate about race cars and imagined a future racing or designing automobiles, not writing screenplays about starships or directing special effects to simulate light speed.

But a life-threatening car accident shifted his focus from auto designer to auteur. Applying to college, Lucas learned of a filmmaking program at the University of Southern California, where he attended and excelled. His 1967 short film Electronic Labyrinth: THX 1138 4EB won first prize in a national student film competition.

Lucas would expand on the short in his first feature, THX 1138, a sci-fi story about an antiseptic future in which sex is forbidden and sedation is mandatory. The film mixes the concepts of Huxley’s Brave New World and Orwell’s 1984 with a powerful visual style. Local sites like BART stations, freeway tunnels and the Marin County Civic Center blend beautifully with sterile white sets and shots of Robert Duvall’s shaved head.

Making Graffiti

THX 1138 flopped at the box office and nearly caused the ruination of American Zoetrope, a San Francisco–based independent studio created by Francis Ford Coppola to help young filmmakers like Lucas make movies outside the Hollywood system.

Coppola suggested Lucas create a more optimistic movie than his dystopian debut, which brought Lucas to his career crossroads project. American Graffiti, a coming-of-age comedy following teenagers throughout the last night of a 1962 summer, was the make-or-break picture that would bridge the gap between THX 1138 and Star Wars.

“I came up with the idea of doing the movie in the (late) 1960s, during the hippie culture. Cruising was gone,” Lucas says in the documentary The Making of American Graffiti. “I felt compelled to sort of document the experience of cruising and what my generation did as a way of meeting girls, what we did in our spare time. I wanted to document the end of an era, document how things change through life passages and to parallel that with what was going on in the United States at that time. The loss of innocence, getting into the Vietnam War … all these issues that center around change.”

Lucas’ examination of innocence may have seemed simple enough on the surface, but American Graffiti is a groundbreaking movie in many ways. The film’s narrative structure, following four main characters with intersecting story lines, was a novelty in American cinema. The film’s sonic texture was also a game-changer: American rock ’n’ roll and pop songs from the late 1950s and early 1960s play constantly, evoking a nostalgic feeling of a very particular time, just before the British invasion. Lucas acquired the rights to more than 40 well-known tunes for $80,000, an incredible bargain by today’s standards.

Lucas shot American Graffiti over 27 nights in the summer of 1972. The movie was supposed to evoke Lucas’ teenage experiences in Modesto, but the filmmaker decided to shoot the movie in the North Bay, close to his Mill Valley home. The first location selected for the cruising sequences was San Rafael’s downtown.

“We started filming in San Rafael, but a bar owner complained that all the film trucks and equipment were bothering his customers,” says actress Candy Clark, who is unforgettable as the sexy, somewhat hard-edged Debbie in the film. “So we packed up and moved the production to Petaluma.”

“We started filming in San Rafael, but a bar owner complained that all the film trucks and equipment were bothering his customers,” says actress Candy Clark, who is unforgettable as the sexy, somewhat hard-edged Debbie in the film. “So we packed up and moved the production to Petaluma.”

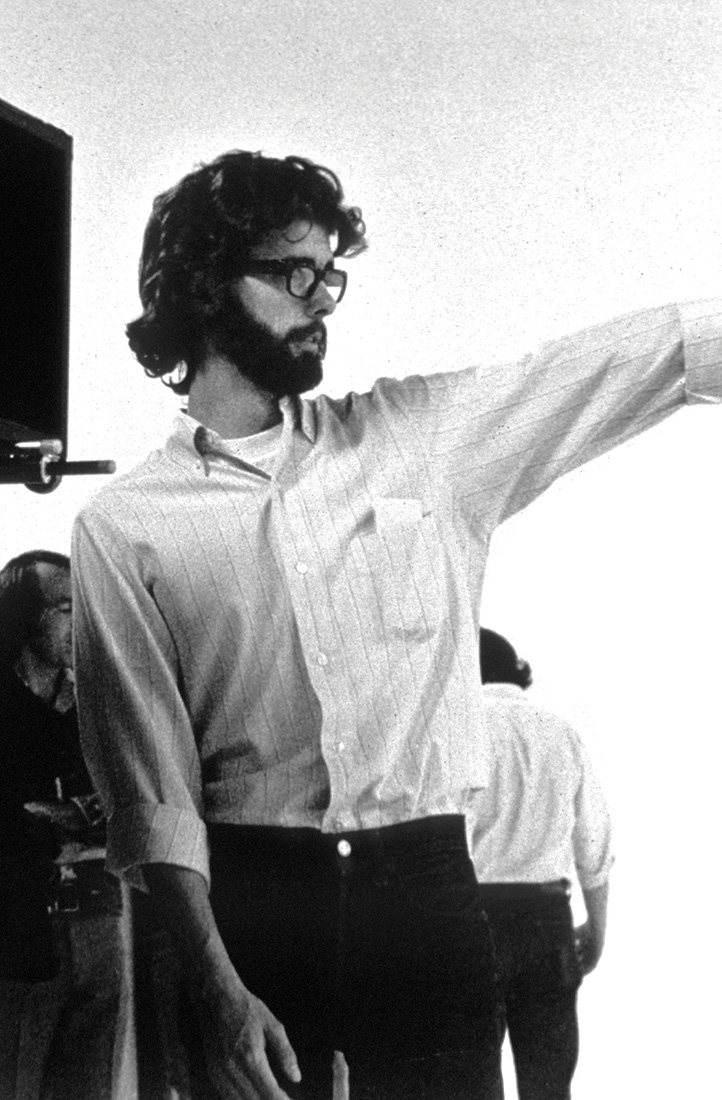

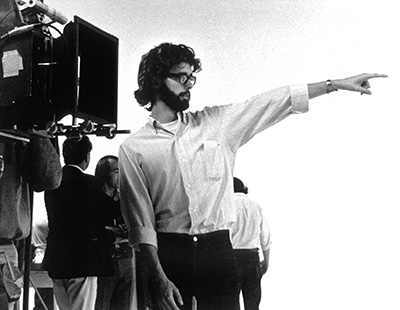

Petaluma leaders welcomed the crew to come shoot every night for a month. Night after night, Lucas and cinematographer Haskell Wexler filmed a cast of then-unknown young actors — including Clark, Ron Howard, Cindy Williams, Richard Dreyfuss and Harrison Ford. Locally the film remains a major point of civic pride, and Petaluma hosts an annual hot rod event called “Cruisin’ the Boulevard” to celebrate the film’s connection to the town.

Lucas also shot in San Francisco at a Mel’s Drive-in that was torn down soon after. A high school sock hop scene was filmed at Mill Valley’s Mount Tamalpais High School, and the “lovers’ lane” sequence, in which actors Clark and Charles Martin-Smith sneak off to kiss, happened near a tributary of the Petaluma River just north of the Novato airport. The film’s climactic drag race was shot at dawn on Petaluma’s Frates Road.

When it came time to screen the film, Lucas made sure Universal’s executives watched it with a packed house of young moviegoers. Every subsequent screening was like a party; audiences loved to ride along with the characters in American Graffiti. Remarkably, the studio heads were still unconvinced the film would be a hit and contemplated relegating the movie to drive-ins or TV.

In the documentary Fog City Mavericks, American Graffiti producer Frances Ford Coppola describes his frustration with a Universal executive following a packed screening at San Francisco’s North Point Theater. Coppola lectured the skeptical executive, pointing out the wildly enthusiastic audience response: “You should be on your hands and knees thanking this young man (George Lucas) for what he has given you,” he said.

Candy Clark remembers seeing the film for the first time in Los Angeles. “When the film started, and ‘Rock Around the Clock’ came on the sound track, people jumped out of their seats and screamed. I thought, ‘We’ve got a hit.’ ”

Into Hyperdrive

Had American Graffiti bombed like THX 1138, audiences likely would have never met R2-D2 or Boba Fett. But American Graffiti succeeded, on a massive scale — it remains one of the most successful films in history in terms of budget to box office. The modest $750,000 picture raked in $115 million in the U.S. alone (adjusted for inflation, that adds up to more than half a billion in today’s dollars and ranks Graffiti in the top 50 most popular movies of all time).

The movie was popular with most critics, although the San Francisco Chronicle panned the film with an “empty chair,” complaining that the movie was “in a class by itself when it comes to tedium.” American Graffiti wound up being nominated for five Academy Awards, including best picture, best director and screenplay, best film editing and best supporting actress for Clark.

Clark says her experience making the movie and the recognition it has brought her is “one of the great experiences of my life. I’ve met people who say they went to see it nine days in a row in the theater,” she adds. “The guitarist Jeff Beck once told me that he has seen the film more than 3,000 times.”

Clark says her experience making the movie and the recognition it has brought her is “one of the great experiences of my life. I’ve met people who say they went to see it nine days in a row in the theater,” she adds. “The guitarist Jeff Beck once told me that he has seen the film more than 3,000 times.”

Lucas, of course, went on to create Star Wars next, which became one of the biggest box office blockbusters and one of the most influential entertainments of all time. It’s easy to forget that 20th Century Fox’s production of Star Wars wasn’t a particularly big-budget film, and Lucas had to deal with issues of studio pessimism similar to those plaguing him before American Graffiti was released. So when it came time to make the Star Wars sequel, The Empire Strikes Back, Lucas financed the film himself so he would not be beholden to the studio. The gamble paid off in a big way, and Lucas was able to build Skywalker Ranch, his high-tech dream factory in San Rafael.

It’s interesting to note that the newest chapter in the Star Wars series, The Force Awakens, will be directed by J.J. Abrams, who was just 11 years old when the first Star Wars was released. A new series of Star Wars sequels and stand-alone adventures will be helmed by directors whose young minds were thrown into hyperdrive, thanks to Lucas’ imagination.

It’s safe to say that this is George Lucas’ galaxy. We just live here.