In May Harvard University’s Make Caring Common project published the results of an extensive five-year study of the sex and love attitudes and habits of young people. While some parents may breathe a sigh of relief that, according to the study, not as many young people are actually participating in the hookup culture as we adults might assume, the reality is that many teens and young adults are lost and confused and not well-prepared to face sexual relations and romantic relationships, let alone protect themselves from sexual harassment and violence. The takeaway, according to Harvard psychologist and researcher Rick Weissbourd, is that we parents should be much more proactive in our conversations about sex and self-protection. Forget the talk… we should be initiating ongoing conversations, not just about sex, but also about love and healthy relationships.

The teenage years are usually a gauntlet in one way or another. When I look back on my teenage years I feel grateful that, inexplicably, I made it through okay. As a precocious teen I was drawn to older boys and men, males I found worldly and dashing and, by my then naïve definition, romantic. My love interests ranged from the cool senior boy when I was a freshman in high school, to the muscle-bound college boy when I was a sophomore, to secretly dating a twenty-nine-year-old jet-setter when I was sixteen. After my junior year of high school I told my parents I was visiting friends at various college campuses when in fact I was sneaking off with this wealthy older man who had utter control of my mind and body. I never considered myself coerced or forced – I pursued him – but there was nothing healthy or mutual about our relationship (and I understand in retrospect that I could have pressed charges for rape if I desired). I was a straight-A student, an athlete, a young woman with dreams and ambitions and strong political opinions who somehow became vulnerable in the face of male attention. Beyond the humiliation of being powerless in a loveless relationship, I made it through unscathed and then, at age 18 during my freshman year of college, I lucked out; I met someone who was three years older and definitely exciting, but was also loving and cared deeply about who I was. He took me on a picnic for our first date and we talked for three hours. That was the end of my attraction to dangerous liasons and I have been with that man, now my husband, ever since.

The teenage years are usually a gauntlet in one way or another. When I look back on my teenage years I feel grateful that, inexplicably, I made it through okay. As a precocious teen I was drawn to older boys and men, males I found worldly and dashing and, by my then naïve definition, romantic. My love interests ranged from the cool senior boy when I was a freshman in high school, to the muscle-bound college boy when I was a sophomore, to secretly dating a twenty-nine-year-old jet-setter when I was sixteen. After my junior year of high school I told my parents I was visiting friends at various college campuses when in fact I was sneaking off with this wealthy older man who had utter control of my mind and body. I never considered myself coerced or forced – I pursued him – but there was nothing healthy or mutual about our relationship (and I understand in retrospect that I could have pressed charges for rape if I desired). I was a straight-A student, an athlete, a young woman with dreams and ambitions and strong political opinions who somehow became vulnerable in the face of male attention. Beyond the humiliation of being powerless in a loveless relationship, I made it through unscathed and then, at age 18 during my freshman year of college, I lucked out; I met someone who was three years older and definitely exciting, but was also loving and cared deeply about who I was. He took me on a picnic for our first date and we talked for three hours. That was the end of my attraction to dangerous liasons and I have been with that man, now my husband, ever since.

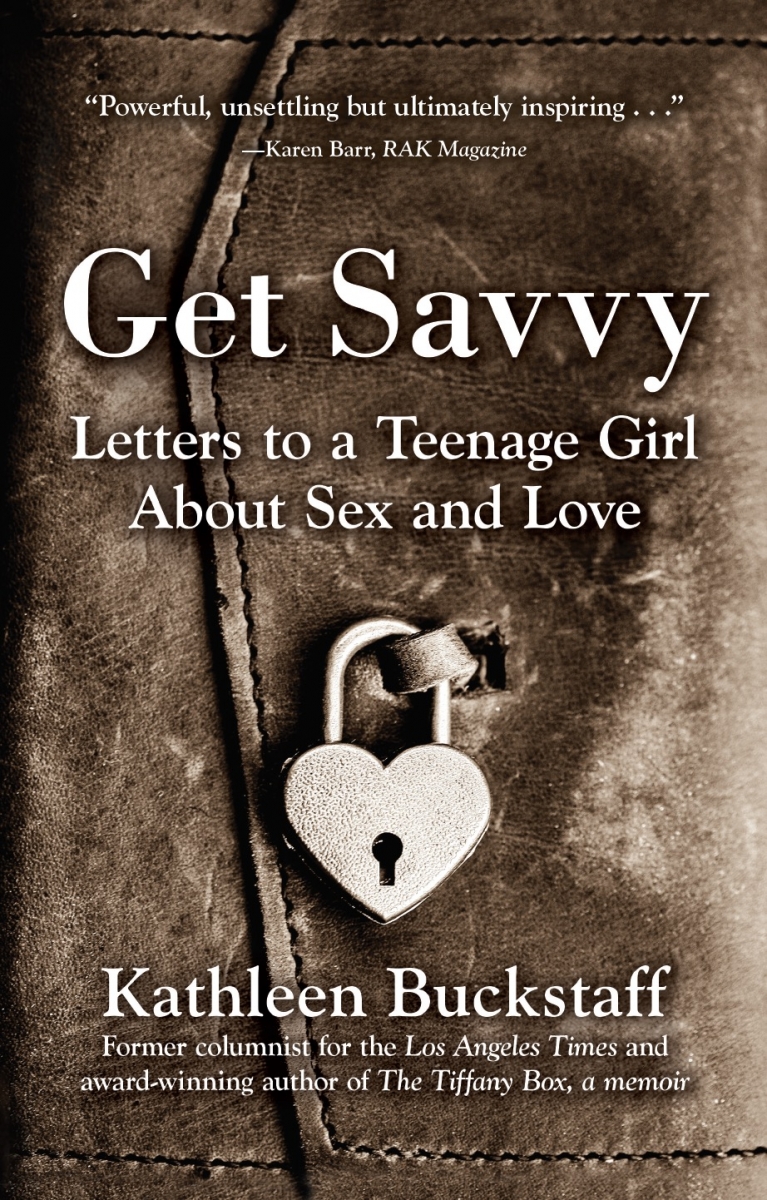

Reading Tiburon resident Kathleen Buckstaff’s new book Get Savvy: Letters to a Teenage Girl About Sex and Love brought back a lot of memories and emotions from my own teenage years, put my experiences in clear focus, and, like the Harvard Study, confirmed my belief that the landscape of romantic and sexual relationships has become even more complex and risky for the current generation of teenagers. Buckstaff wrote this book as a way to turn the hardship of her own experience with sexual assault into something helpful, something she could have used to protect herself when she was a young woman. She details the sexual abuse she endured at a prestigious New England boarding school – and her own PTSD when her daughter reached the age she was when she was abused – in a series of letters to a teenage girl (i.e. all young women), while interspersing outtakes from the interviews of over 60 college students, recent graduates, healthcare professionals, self-defense instructors and professors, weaving these quotes and information from hundreds of academic studies carefully around the framework of the narrative. The first half of the book is propelled by Buckstaff’s personal story, the long-term fallout and painful lessons gleaned, while the second half of the book focuses on the physical safety, health and well-being of the young woman she is writing the letter to, providing tools in each chapter, from thoughtful opportunities for reflection to very practical preparation for specific situations.

The book does several things well, and one of them is to negate the possibility that there is anything remotely romantic about an older man’s sexual attentions toward a teenage girl. Simultaneously, it allows us to recognize the life situations and emotional states that would compel a young woman to go along with advances from a dominant male. It identifies the vulnerabilities that a sexual predator, older or not, capitalizes on and deconstructs the social environments and psychological nuances that culminate in abusive situations.

Another thing the book does well is to provide a profile of the healthy psyche, male and female, that will be able to stay safe in complex social situations and avoid obstacles that get in the way of a healthy relationships. These obstacles are not particular to any given era; the same things that allowed for Buckstaff’s ongoing sexual abuse thirty-five years ago exist in the exact same form today and play out in the exact same way. This makes her story and the advice around self-care and self-protection timeless, relatable for both young readers and their parents. The need for discussions around not only self-care, but care in general seem particularly urgent in an era where loveless hooking-up is an accepted norm, not the exception.

Another thing the book does well is to provide a profile of the healthy psyche, male and female, that will be able to stay safe in complex social situations and avoid obstacles that get in the way of a healthy relationships. These obstacles are not particular to any given era; the same things that allowed for Buckstaff’s ongoing sexual abuse thirty-five years ago exist in the exact same form today and play out in the exact same way. This makes her story and the advice around self-care and self-protection timeless, relatable for both young readers and their parents. The need for discussions around not only self-care, but care in general seem particularly urgent in an era where loveless hooking-up is an accepted norm, not the exception.

I have two daughters in college and a son in high school, and the material in this book feels poignantly relevant. My children are not overly revealing of the details of their social lives, but we have had dinner table conversations about the prevalent culture, one in which sex might as well be any old athletic event. My kids, like many in the Harvard study, have not dated much in high school because they are not comfortable with the default dynamics and are looking for something more meaningful. The reality is that the scene is difficult to navigate without making compromises, and with notions of courtship being passe, there are not a lot of examples of how to forge your own path. So, while we parents fret about the big sex talk, we may be overlooking the most important conversation (or, even better, conversations) of all: the talk about forming and maintaining healthy relationships.

To some extent conversations will happen in Health or Sex Ed classes at school, but according to Stephanie Searle, my children’s Health teacher at Novato High, there is a broad range of material to cover in Health class, and it falls upon the individual teacher to provide meaningful material and go in-depth into both assault prevention and healthy relationships. Searle, who I know first-hand is proactive and invites excellent speakers in to conduct conversations and workshops, points out that even with significant programming, some students will not truly participate and respond in class.

Buckstaff’s book seems to be an excellent place for parents to begin conversations with their children about self-protection from abuse, and also about forming healthy relationships. The interview subjects give insight into the details of today’s social landscape, while Buckstaff’s research provides specific analysis and language to identify warning signs. For example, she describes the seductive romantic behaviors of the “conquest male” vs the healthy romantic behaviors of a “noble male.” She offers preventative approaches such as the PIG system: if a guy is P – pushing drinks and I – ignoring wishes then G – go home. I wish I could go back to visit my fourteen-year-old self and hand her this book. I wish that my young self could read Buckstaff’s story, and the testaments of the dozens of others.

The book, rife with cautionary tales and detailed preventative practices, is also surprisingly inspirational when it comes to love, offering truly beautiful sentiments from Buckstaff and the young people she interviewed. I will leave you with one I found to be particularly tender, a description of true love by a young woman named Sophie, 22:

“I had a professor explain static aesthetics to me. When you’re looking at Monet’s haystacks, you miss the beauty of it when you start analyzing it. I’m interested in that moment when something ceases to be a means to an end. It transcends utility. My professor explained that that is what art is, and that is what love is. When you talk about love, that’s when someone isn’t a means to an end. They exist totally in their own otherness, and it’s not about explaining or naming or labeling them, and it’s not about using them.”

Kathleen Buckstaff’s book is available on Amazon here: Get Savvy: Letters to a Teenage Girl About Sex and Love

You can also learn more about her work on the Get Savvy Facebook Page.

Kirsten Jones Neff is a journalist who writes about all things North Bay, with special attention to the environment and the region’s farmers, winemakers and food artisans. She also works and teaches in school gardens. Kirsten’s poetry collection, When The House Is Quiet, was nominated for the Northern California Book Award, and three of her poems received a Pushcart nomination. She lives in Novato with her husband and three children and tries to spend as much time as possible on our local mountains, beaches and waterways. For more on her work visit KirstenJonesNeff.Com.