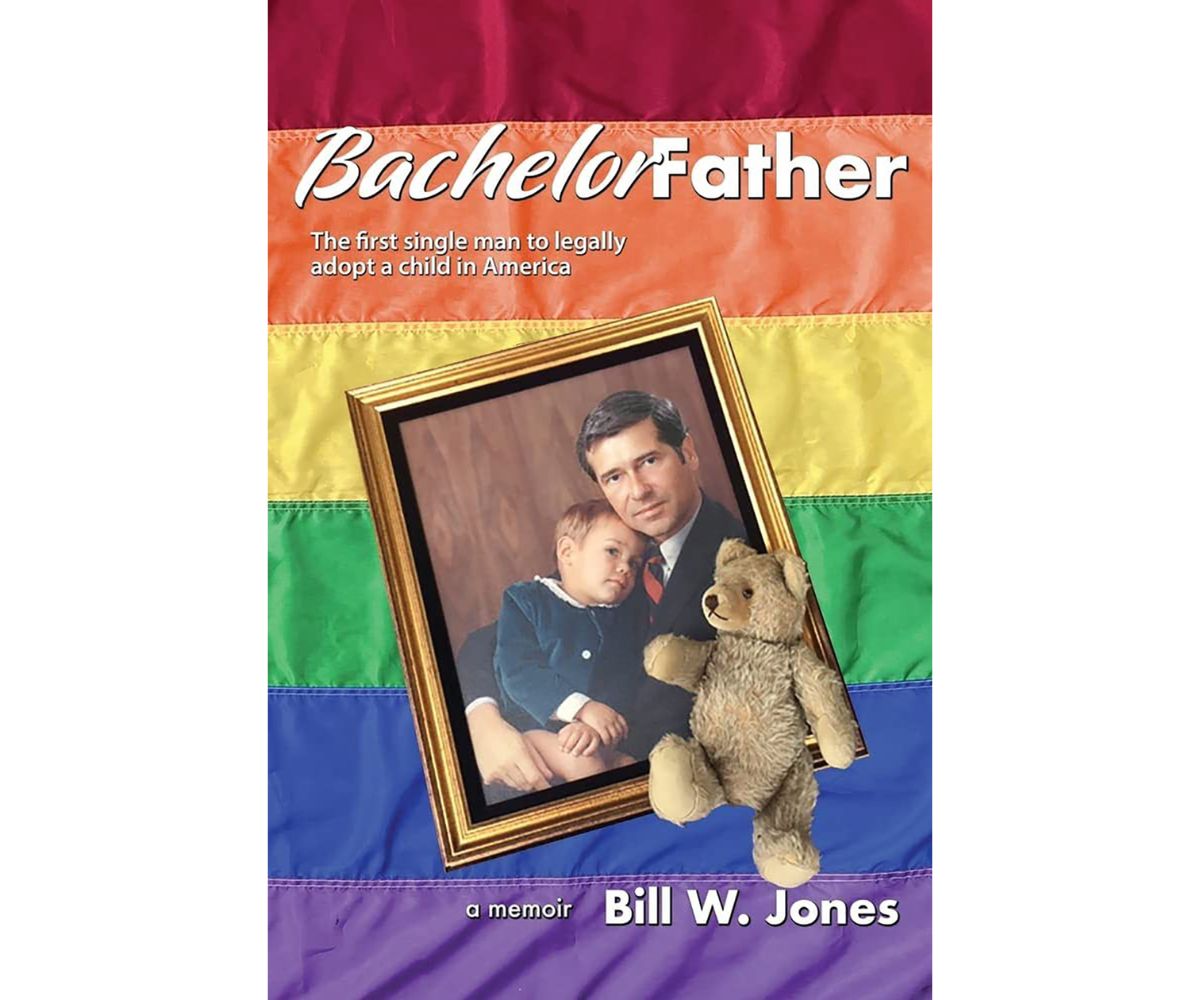

This is my story about the document I signed as a single man in 1969 that became a worldwide news item. It’s a story that compelled me to take a memoir class at the age of 86, the OLLI workshop at San Rafael’s Dominican University, where I wrote about my birth up until the adoption of my son at age 39. The second part was written for a support group of writers and is about what I went through as a closeted gay man who, by chance became the first single man in America to be allowed to adopt a child through a government agency — that child being Aaron Hunter Jones, my son. Its raw honesty may make you want to avoid me, but tales of my incredible dream that came true, turning my life into a perfect storm and flooding it with love, has kept me alive these 95 years. Some of the chapters were so gut-wrenching for me that my friends had to take over reading them to the group.

How It Happened

Dorothy Murphy, the head of the San Francisco Social Services Adoption Agency, a good Catholic girl, was terrified that some conservative women’s group would find out what she was up to and start picketing her building, thus ending her secretive new policy. She was desperate to find homes for 850 unwanted, undesirable, unadoptable children. In 1967 if you were over 6 months old — unless you were a were a white, curly haired, dimpled Shirley Temple knock-off — chances are you would spend your life in foster homes, one after another, until you were released on your 18th birthday.

Abortions were illegal and expensive; the “pill” hadn’t been invented yet; and young “hippies” had not yet cursed the world and declared, “Screw you! I’m keeping the kid!” The stockpile of lonely children left in foster homes grew, but Dorothy knew a way that would find loving homes for a lot of these kids. I was sworn to secrecy when I signed up to adopt under her new, controversial policy, one that had never been tried before allowing single men and women to adopt.

My Backstory

I was just 2 years old in 1930 when my incompatible parents split, going their separate ways and abandoning me to the care of our next-door neighbors for a while, then grandparents, then an aunt I hated. I don’t remember any sunny days, but the black nights in my dark bedrooms, when I cried myself to a fitful sleep, still haunt me. I know the intense loneliness a child feels without a mother’s arms or a daddy’s lap.

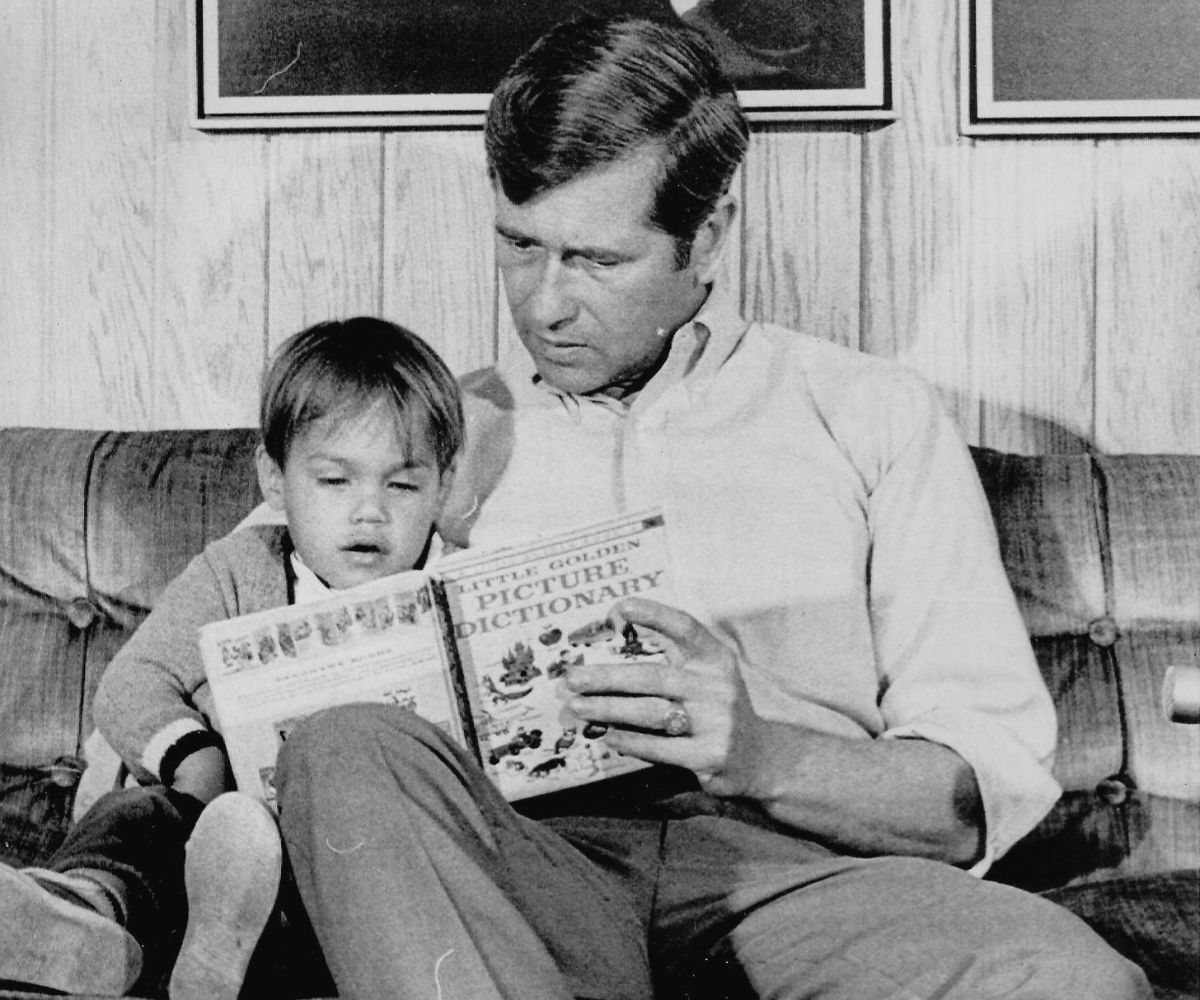

I was 11 when my mother, who had finally remarried, gave me a present: a baby brother! I was in seventh heaven because it was my job to care for him every day after school while my mother worked in her restaurant and bar. He considered me his parent, and it didn’t end as we grew older. I loved it, as I loved the steady stream of pets I was a “parent” to: dogs to run and play with; purring kittens on my lap; a monkey who would sit with me at the Trade Winds bar in Sausalito until it was 86’d for grabbing a customer’s martini and gulping it down; pet birds and fish; a hamster; and the one pet I loved the most — the most affectionate, most clean, most adorable baby skunk I bought in a pet store when I was a fifth-grade teacher in Novato.

It was 1954, the Catholic “Year of the Blessed Virgin” and she was a virgin, so I named her Bee Vee since I couldn’t say the word virgin in my classroom. Yes, she went to school with me every day and was the class pet, available for petting when my students finished their schoolwork. She wore a harness and leash when we walked down Bridgeway to Willie’s Marin Fruit grocery store. I can still hear the squeal of brakes and see the shocked faces glaring at us from the cars.

I loved each and every student in my classes and loaded them up in my station wagon on weekends to visit the museums, a hot dog factory, Fisherman’s Wharf, the base of the Golden Gate Bridge to throw sealed bottles with notes written by them into the bay and so on, but it only made me surer than ever that I wanted a child of my own.

Early Attempts

I flew to Cuba in 1959 because I was told there were thousands of Fidel Castro’s orphans that needed homes. True, but not the home for a single male; the nuns at the orphanage, Batista’s summer home in Varadero Beach, made that quite clear.

I even got myself invited to one of the Sexual Freedom League parties in Berkeley hoping I could be aroused by a woman and then possibly have a son or daughter the old-fashioned way, but I only got as far as hugging a beautiful naked woman. It just wasn’t in the cards for me, and I left feeling depressed and unfit.

The longing for a family of my own, a child of my own, ended on February 13, 1969, when I signed the adoption papers at City Hall in San Francisco. Miracles do happen, and at 94 I can tell you I self-published a book about it — all of it — the lies I told; the secrets I’ve lived with; the profound joy of being a father to my son, Aaron; the profound heartbreak of being a father of a schizophrenic son who died at the age of 30 with an empty syringe of pure heroin in his hand.

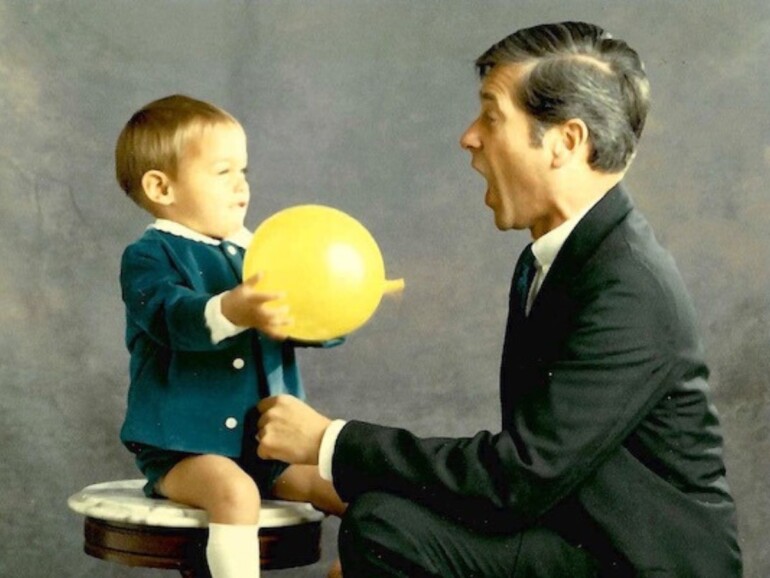

Ultimate Father’s Day

My story is a common one, one that many of you share with me, but I had to write this book to clear the air. I am known in many countries as well as in America as the first single man to legally adopt a child in America. A reporter at the San Francisco Chronicle found out that the city was about to let me, a single man, adopt a little boy, but we pleaded with him not to print it until the adoption was finalized. Otherwise, Dorothy’s controversial policy would be shot down, brutally keeping foster kids from finding warm, loving homes — homes with single moms and single dads. The Chronicle waited until after I had signed the adoption papers, and then on Father’s Day of 1969 our story with photos covered the entire front page of Sunday Women’s Section. The Associated Press sent the story all over the world and I started getting heartfelt letters from England, Austria, France, Ireland and Italy, among other countries.

Someone sent me a poem that I have repeated hundreds of times to myself. It calms me. Strengthens me. Ties my heart to my son’s heart.

Not flesh of my flesh,

Nor bone of my bone,

But still miraculously my own.

Never forget for a minute,

You didn’t grow under my heart,

But in it.

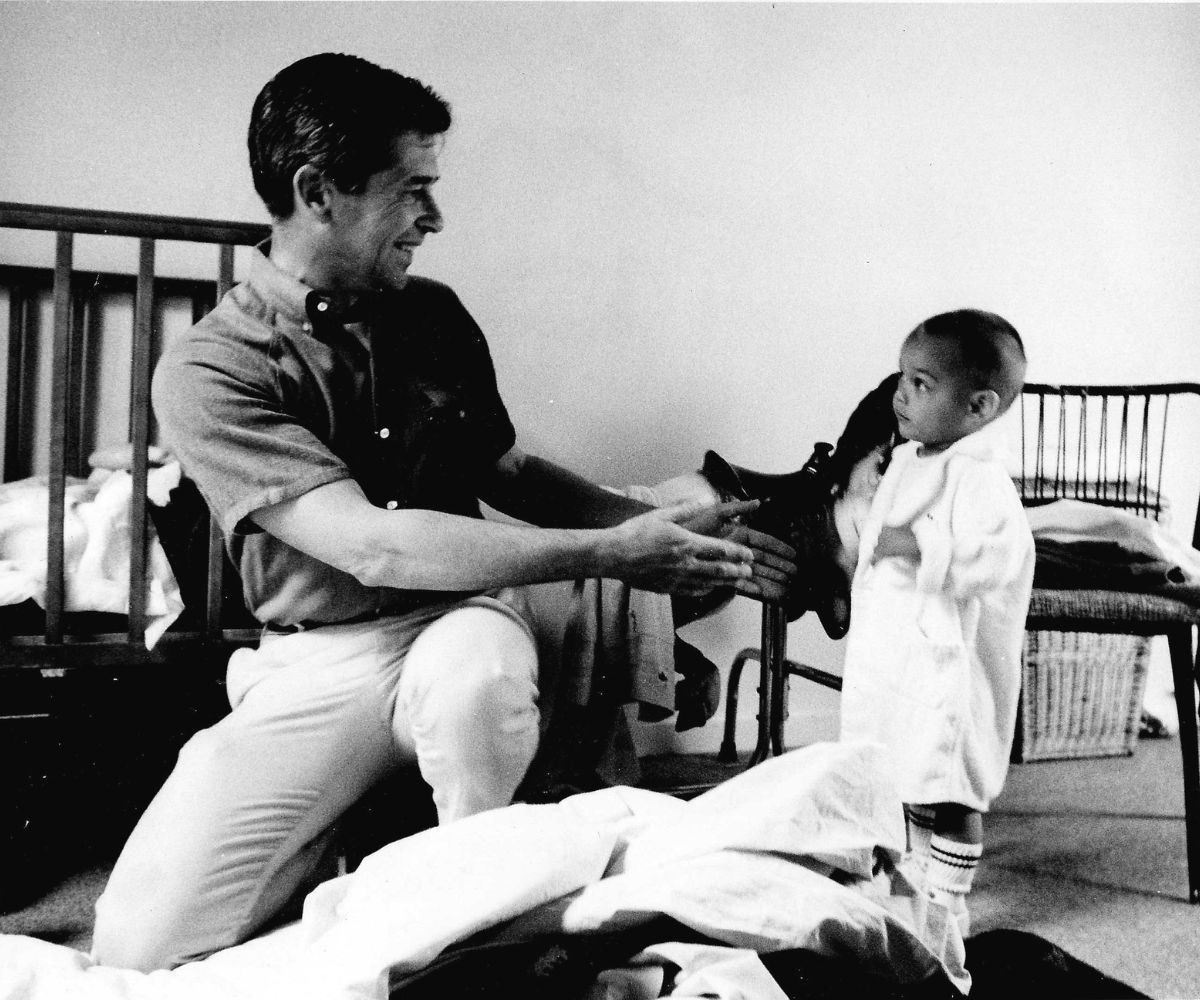

Aaron and I were flown to New York City to do the “I’ve Got a Secret” show and to Philadelphia to do “The Mike Douglas Christmas Special.” The one thing I insisted on was that they would not ask me about my love life — it was respected. No one asked me, but I’m telling you now: The first single man allowed to adopt a child in America was and is homosexual.

It’s not a big deal in today’s world, but in 1967, ’68 and ’69, you could be arrested for holding another man’s hand in a bar. If “outed,” you could be evicted from your apartment, lose your job, be ostracized from your church, or worse, have your family and friends close their doors to you. And so I lied, as I had lied my whole life about who I loved for fear the truth would not set me free, but instead cause me to lose the one I loved the most, my son.

My memoir, Bachelor Father, didn’t start as a book. It started as homework in a workshop on how to write a memoir, taught by Diane Frank at OLLI. OLLI, a.k.a. Osher Lifelong Learning Institute, can be found on the Dominican University campus right here in San Rafael. The other classes, including art history, current events, film studies, ornithology and others, are offered as lectures with film clips, live music, etcetera, but no — I repeat — no homework except in Diane’s inspiring writing classes.

I went back to school when I was 86. Do the math. It’s taken all these years to wrestle this “homework” into a 423-page doorstop. Lots of tears spilled over the pages. Lots of clock ticking while I stared into space digging for just the right word or phrase. Lots of dawns as I staggered away from my computer over to my bed.

If I had just written about the adoption, it would have had a happy, victorious end and would have satisfied any reader, but our story didn’t end there, so I kept writing and writing and writing. The hardest part of writing a memoir is knowing when to stop. When I turned my manuscript over to a professional reader, John Geoghegan, who also lectures at OLLI, and he told me a book should be less than 100,000 words, I felt like I was falling into a pit with no bottom. I had written over 200,000! I was bewildered. Each chapter was like a child I gave birth to, and I was told I had to kill half of them. I couldn’t bear to pick out the children (chapters) to murder.

That’s when Elinor Gale, another long-time writing student of Diane’s, came to my rescue. She was a professional editor, and her sarcastic Dorothy Parker humor tickled my insides, but I trusted her judgement. We were finally able, in our deletion tug-a-war, to chop off 50,000 words — still too many words for a publisher to accept, so that left just one option: self-publication.

Brian Johnson, a dear friend and computer nerd, scanned the 33 photos and set up Dropbox for Elinor and I to do our murderous deed. Another friend, Barry Power, who had nagged me for three decades to write my story, helped me design the cover and graphics inside.

I wrote the book, but like what Hillary Clinton said about raising a child, it took a village to publish it. And why did I write it?

I want the world to know you don’t have to be chaste or perfect to love and care for your child. You don’t have to be married or even a couple. You can be straight or gay, a man or a woman, or something in between; any race, any religion, any time, any place; rich or poor; athlete or handicapped.

Belonging, devotion and caring intensely are the common denominators. To hold your child and feel the bond, that sacred bond, is worth living for, and in my case, fighting for.