Enough already. That was my prayer. Circumstances had accumulated into a layer cake of dread. I couldn’t force down one more slice. I couldn’t do it anymore, not one more day, maybe not even one more hour. How do you find strength when you’ve already been emptied out so thoroughly?

I’d dressed after the scan then waited to be told to go home, just like the last three years. I was in a high-risk group, which necessitated this one-stop shopping mammogram with an onsite radiologist. But I felt like an imposter in the high-risk waiting room, I’d been diagnosed with something called atypia a few years back, abnormal cells, but not cancer; maybe something, probably nothing. This day, I am led into a small office. “You need to see a surgeon,” said the woman with a conspicuous box of Kleenex on her desk. But I wasn’t sad. I was angry. This was a mistake, probably more atypia… “I can call your surgeon and make an appointment,” she offered. I listed all the reasons that I couldn’t have cancer and wouldn’t need the appointment. The kind of excuses that get you out of jury duty, caring for my son with a brain tumor, two other children who’d already been through too much. I was confused. I mean, yes, I was high risk-y because of the previous biopsy, but breast cancer didn’t run in my family. Then again, neither did brain tumors.

Our family had been orbiting my son Mason’s inoperable, slow growing brain tumor for five years by then. There had been partial eclipses, periods of uneasy peace punctuated by held-breath MRI scans, maybe something, maybe nothing biopsies, chemo, and then the massive cerebral hemorrhage that landed him (and us) in hospitals for six months. He was 15 now, and he’d had to learn to walk, talk and eat twice in his short life. It was my job to bring Mason back into the suit of himself, while mothering all three of my children with the same level of love, perseverance and presence, tumor or no tumor. These were impossible standards, but they were my standards. The thought of breast cancer was ridiculous. This Marin County family had already paid, but of course the cells in my breast knew nothing of my rules.

It’s difficult to put into words what it was like to live in a body that was turning against me, the recoil then the realization that it’s me I’m recoiling against. I’d done what I was supposed to, nursed three babies, ate my servings of leafy greens; I didn’t drink or smoke; I exercised, even meditated when I could sit still with the “to do” list that looped in my mind. I did it all, yet still…

“We’d rather be anything than powerless,” my friend Annie said as we hiked the ridge at Deer Park. It was true. When Mason was diagnosed, I felt such judgement, but mostly it was coming from me. If only I’d breast fed him longer or found a competent neurologist sooner; if only I’d never introduced foods like birthday cake or jellybeans. It was a MadLib of self-blame, weirdly comforting. Because if I caused the problem, I had the power to fix it. This thinking was more distraction than solution. Ultimately, I had to put the question why on a shelf along with my guilt and overblown sense of responsibility. I had to accept the reality that my son had a tumor that would shape all of our lives. Still, I had always thought I could keep up the pace, drive him to his many appointments, figure out yet another PT strategy, another nutritional approach, Chinese medicine, homeopathy, acupuncture, chiropractic. So many appointments, and then there was the broth I made just for him — not me — healing with vegetables and seaweed.

After a surgical biopsy, I was diagnosed with Stage 0 cancer, ductal carcinoma in situ, DCIS, a very treatable cancer, the cancer you’d pick if you absolutely had to choose one. I opted for mastectomy, in consultation with my breast surgeon and after much research. I didn’t know the answer for anyone else (and I still don’t), but I knew what was right for me. By now I’d learned to trust that quiet, still voice that comes from deep inside, the one that doesn’t need a lot of words. The direction was clear, now I just wanted to skip to the part where I’m sitting on the beach a year from now holding my husband’s hand while our kids chase the dog in the surf.

The fact of my mortality probably wasn’t news to anyone else. But I’d been acting like I could push the universe into an acceptable plan for our lives through the spectacular force of my will. This meant that I would live long enough to see my children safely launched into the lives I’d planned for them. I withheld my approval from the reality we’d found ourselves in. It was the spiritual equivalent of holding my breath until the weather changed. Yet, here we were in the midst of storms, still and again.

I woke up from the surgery re-arranged, though it would take time for wounds to mend, and the shape of this new body and spirit to be revealed. I was still angry at whatever force in the universe hands out pediatric brain tumors and breast cancers to the mothers of already anxious children. Though I’ll never forget that night in the hospital after everyone left: a nurse came into my room with a comb and gently untangled my hair, surely she had other things to do. There was kindness in that moment, a generosity of spirit, and I let myself receive it.

This seemed to be the point. For years, I’d been waiting to get the life back that I recognized, hunkering down until something changed. I told myself that I’d be happy when, I’d relax after… Yet here was the life I had, marked with scars and stains. There was also profound healing and unexplained goodness, and always a love big enough. A salve for all those places emptied out of plans, safety and surety.

It was Mason’s turn to walk with me. Slowly my strength was coming back. I’d forced myself to venture out half a block or so every day. Mason’s gait was uneven; he walked with the exuberance of a baby giraffe who wobbled a little more on the right. I stepped intentionally, to avoid engaging the hurt parts of myself. We passed under the stand of redwoods, and Mason held my hand as I stepped over the puddle where water ran down the street year round. It was a stream paved over years ago and yet never gone, a source that runs clear, cool, and nourishing no matter what pavement gets in the way. Mason smiled as he steadied me, happy to be the one giving help instead of receiving it. We had the strength we needed, one step, then the next. It wasn’t out there, somewhere else. It was on that mossy, slippery sidewalk, in that moment and nowhere else.

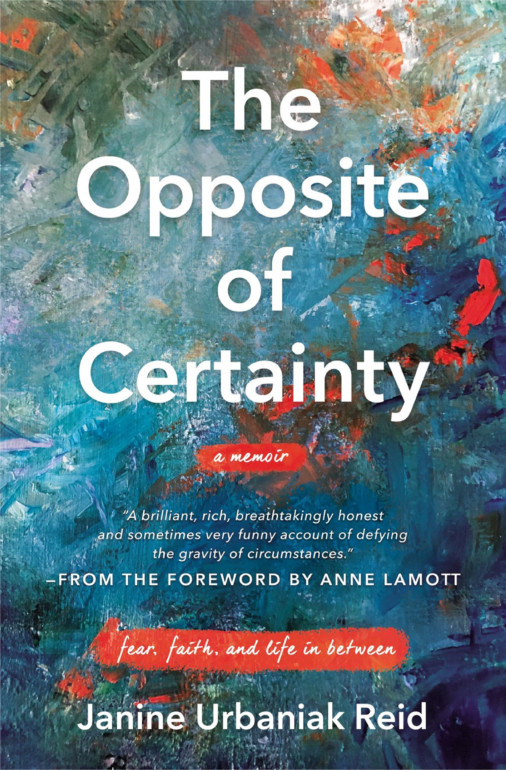

Janine Urbaniak Reid is a long-time Marin County resident. She is the author of The Opposite of Certainty: Fear, Faith and Life in Between. Visit her at JanineUrbaniakReid.com.

How to Help

There are so many local businesses that need your help right now. For more ways to support local businesses, go here.

For more on Marin:

- The Best Cocktails to Get To-Go

- CEO Julie Wainwright On The RealReal, Her Luxury Consignment Business

- 8 Bay Area Bookstores to Support on National Indie Bookstore Day

Janine Urbaniak Reid was born in Chicago and grew up in California. She graduated from the University of California at San Diego. She has been published in the Washington Post, Chicago Tribune, San Francisco Chronicle, and widely syndicated. Hoping to bring humanity into the healthcare discussion by sharing her experience as a mother of son with a brain tumor, she penned a piece for the Post which went viral. She has been interviewed on national news networks, and continues her work as a spokeswoman for healthcare justice. She lives in Northern California with her family and a motley assortment of pets. v

Janine Urbaniak Reid was born in Chicago and grew up in California. She graduated from the University of California at San Diego. She has been published in the Washington Post, Chicago Tribune, San Francisco Chronicle, and widely syndicated. Hoping to bring humanity into the healthcare discussion by sharing her experience as a mother of son with a brain tumor, she penned a piece for the Post which went viral. She has been interviewed on national news networks, and continues her work as a spokeswoman for healthcare justice. She lives in Northern California with her family and a motley assortment of pets. v