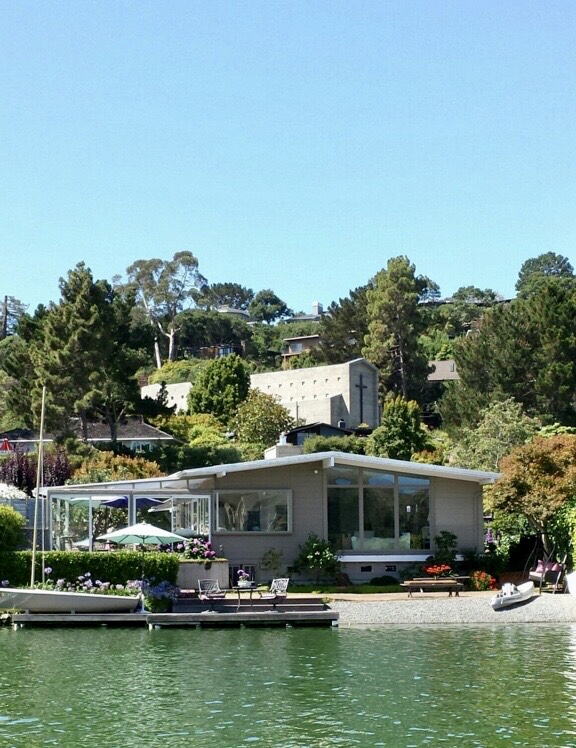

My 94-year-old mother lives in our family home in Belvedere. For much of the year, I leave my apartment in New York City and live there with her. My sister Laurie, who lives close by, and I use the house as we did when we were kids — like a closet. We sleep outside. We eat outside. We read, write, paint, visit with family and friends and tend to the garden. We swim, kayak, paddle, sail and float on the lagoon. We have fierce ping pong battles on the patio. We sit quietly watching the light change. And we are flooded with memories of our childhood on the Belvedere Lagoon.

Behind our gate we are nestled into nostalgia. The old apple tree. The same white posts holding up the house. The bricks that my grandfather laid down seventy years ago. The warm pea gravel under my bare feet on the beach that extends out into the brackish lagoon.

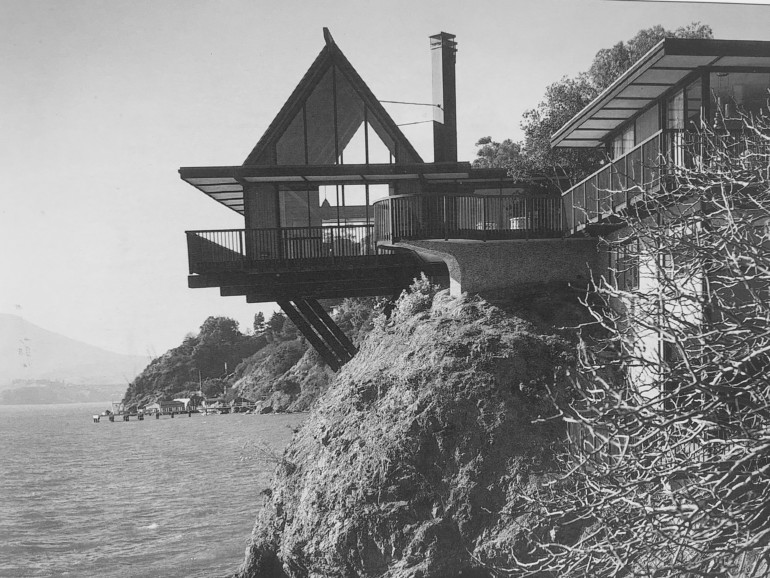

In the morning I warm my legs next to the heating duct in the dining room wall that warmed me as a child. I look out the same windows that once showed me empty hills dotted with black and white cows and not a house in sight. The golden hills are now covered with oak and pine trees and copious houses, but my memories are of mid-century architecture by Joseph Eichler, Appleton and Wolford and George Rockrise. One level. Glass to let the light in. Elegantly pitched roofs. More recently, FEMA has forced some new homes to start seven feet above sea level; these towering new houses are eclipsing the sweetness of the homes that dominated my childhood.

We made forts under the eucalyptus trees and sucked on the stems of oxalis — we called it sourgrass. Wild California poppies sprung up in the most delightful places. The sweet smell of plum, apple, orange, pear and lemon trees lingered in the air. You could walk a few steps and the bay trees with eucalyptus gifted you with a forest scent. Honeysuckle and rose bushes with fresh air from the Pacific could stop you in your tracks.

There was a particular hill that was covered with ice plant. We would stash waxed boxes from the grocery store under a tree. When the mood came, we would hike up to the top of the ice plant hill and — God help us — fly down, careening into the street below.

Going to Richardson Bay when the tide was out, we would overturn rocks and send crabs futilely scattering. New kids would get pinched with every grab, but we were good at catching them — we knew just how to dance with the claws until a clear moment came when you could hold the back of their shells. We would skip stones across the water; twelve skips is my personal best.

I remember scavenging under the Farr Cottages that cantilevered over the San Francisco Bay looking for sand glass, usually in my bare feet, the bay mud squishing between my toes. There were so many colors, but we always coveted the blue.

Most weekends and all holidays our cousins came with their sleeping bags in hand to spend family time with us. Our cousins made us a gang of five. We were often involved in competitive games; king of the raft was a favorite. The boys frequently fished from the dock, only rarely reeling in striped bass or a completely harmless leopard shark. Often there were young bat rays that entered the lagoon. They sometimes grew to a five-foot wingspan, calmly skimming on the surface.

We walked with buckets to what is now West Shore Road and dug in the mud flats. We’d look for an air bubble and then dig like mad until we found clams, then haul them back to my grandmother, who had a pot of boiling water ready. Within minutes we would be feasting.

My sister and I would go to the Embee Market on the Boardwalk and ask the produce manager if he had any old carrots or apples that we could take to Blackie, the horse pastured by the train trestle. He always obliged us. We’d walk with our bag of treats down the railroad tracks. Along the way we would feel the rails for vibrations and listen for the train. We’d put pennies and nickels on the tracks and wait for the train to flatten them out. The engineer leaned out his window, waved and pulled his whistle. Anise Hyssop — we called them licorice plants — lined the tracks and made a nice snack for us as we made our way to Blackie’s pasture to feed carrots, apples and sugar cubes to that beloved old swaybacked horse.

We’d crawl under the Boardwalk to find nickels, dimes and quarters, then race to the Standard 5 &10 to buy Sugar Daddies, Milk Duds, red licorice and Pall Mall or Kool bubble gum cigarettes.

On the lagoon we were ecstatic when the wind was fierce… all the better for sailing our Sailfish. There was no such thing as sailing clothes. Not a life jacket in sight. We capsized on purpose, throwing ourselves over the side, landing on the centerboard and righting the boat without touching the water. There was great pride in the glory of riding the boat upright. And playing in the lagoon until our lips were blue. My sister and cousin Teresa would run to the shower to warm up, leaving absolutely no hot water for the boys.

This island has always been a haven for birds. Located on the Pacific Coast Flyway, it’s a stop for migrating ducks, cormorants and terns. Year-round residents include pelicans, geese, great blue herons, snowy egrets and kingfishers. Playful families of river otters enjoyed the lagoon, too.

We hiked for hours on Tiburon hills in search of Miwok arrowheads, which we occasionally found. We were usually covered in dust, dirt and foxtails from the fields of gold. Oak trees gave us shade. Lizards were a thing of humor and delight. Snakes were to be avoided, at least by me, but I knew kids who loved to catch them. Tall-eared jack rabbits would leap into sight, our dogs on their trail in seconds. But they were no match for wild hares. We were all very fit, muscled from hours of play. Endurance athletes had nothing on us.

There was a favorite dead end on one of the roads on Belvedere Island. It was flat for quite a ways but then became extremely steep. We would walk our bikes up as far as we could. Turn the bike around. Our passenger would get seated on the spring-loaded book holder on the back fender, and on the count of three we would lift our feet and let the bike zoom down the hill, never thinking a car might be backing out of a driveway. And then we’d do it again.

I could ride my bicycle anywhere… well, almost anywhere. I wasn’t allowed to go to the arcade on Main Street because that was where the “bad kids” hung out. No helmet. I rode sitting on the handlebars while my childhood friend Graham peddled us to our destination. There was no interaction with parents until the 4:30 p.m. whistle blew and we knew it was time to head home.

On Sundays we would be excused half way through the service at St. Stephen’s to go to Sunday school in the lower half of the building. The hallway was dank and dimly lit, and it was always thrilling to be a little scared as we raced to class. I was baptized, confirmed and married in that glorious church.

Our grandfather had a workshop attached to the carport. The small shop had a distinctive musky, wood-and-rust scent. His tools were carefully organized. Hammers and screw drivers on the pegboard. Little baby food jars filled with nuts and bolts according to size tacked to the bottom of a shelf. Coffee cans filled with odd shaped nails. A metal cabinet housed a variety of Blue Diamond smoked nut cans that held paper bags of screws and assorted functional parts.

My grandfather was a Harvard-educated mining engineer who built his five grandchildren paddle boards — he was ahead of his time — and rafts, and, for me, a dollhouse out of thin plywood. It was a simple box with partitions that created four rooms. I would spend hours finding small objects for tables and chairs, and sew bedspreads and curtains from old fabric. As I got older, I would hide it in my closet so my friends wouldn’t see it and tease me, but at night I’d open the closet door and work on my little house. I made paintings. I glued my mother’s compact mirrors on the walls. I created elaborate doors that didn’t open. For special occasions, I repainted the rooms and rearranged the furniture.

In Growing Up Belvedere-Tiburon, I write about the joy and beauty of Belvedere. Like any town we had our share of tragedy. In the 1960s and ‘70s at least six of my friends died before the age of 20. Some from drugs, others by suicide. I see some of the parents of those children now; all these decades later, there is still sadness in their eyes. As my grandmother would say, “There but for the grace of God go I.”

But it’s the things that stay the same that stay with me. The bellowing of foghorns is still the music of my morning. We hike the lanes in Belvedere. We get out on the water as often as possible. My grandfather’s workshop is now my studio. I tend his garden, hang my paintings on his walls and gaze up at St. Stephen’s Church. And if I blink, I’m back in the Belvedere I knew as a child.

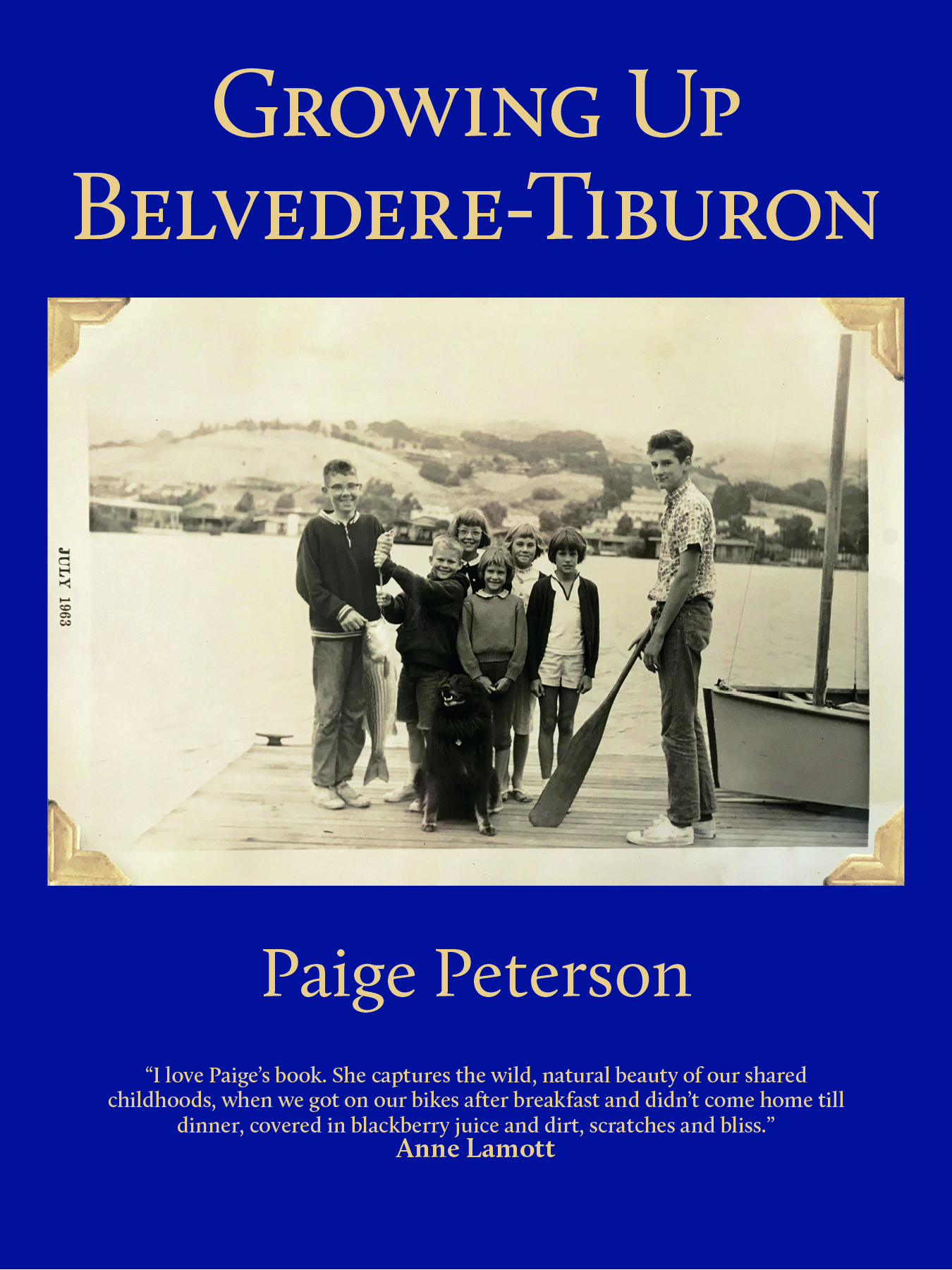

Growing Up Belvedere-Tiburon, a table top book, will be published in December by the Belvedere-Tiburon Landmarks Society. It is filled with spectacular archival images of Belvedere and Tiburon. Belvedere resident Phillip Moffitt, the former Editor-in-Chief of Esquire magazine served as an advisor on this project. This book is available to purchase at Book Passage — all proceeds will go to support the Belvedere-Tiburon Landmarks Society.

How to Help

For more ways to support local businesses, go here.

For more on Marin:

- Marin Chefs Share Their Favorite Comfort Food Restaurants & Recipes

- The Newsoms, California’s First Couple: From Marin to the Global Stage

- Two Bay Area Restaurateurs Embark on the Trekking Trip of a Lifetime – Right at the Start of the Coronavirus Pandemic

As a journalist, Paige Peterson has contributed to Marin Magazine, New York Social Diary and the National Council on U.S. Arab Relations. As an illustrator, she has collaborated on “A Christmas Carol,” adapted by Jesse Kornbluth, and “Blackie: The Horse Who Stood Still,” which she co-authored with Christopher Cerf. As a painter, she is represented by Gerald Peters Gallery in New York City and has been honored by The Guild Hall Academy of the Arts in East Hampton. She is a consultant to the Attitudinal Healing International organization and the Huntsman Cancer Foundation. Paige is the Author and Artist in Residence at Literacy Partners. As a photojournalist, Paige has reported extensively about the Middle East. She serves on the board of the National Council on U.S. Arab Relations, is an International Conservation Communication Specialist at Safari West, and Cheetah Conservation Fund Ambassador to the Middle East. Paige and her two grown children live in New York. Ms. Peterson splits her time between New York City and Belvedere, California.

As a journalist, Paige Peterson has contributed to Marin Magazine, New York Social Diary and the National Council on U.S. Arab Relations. As an illustrator, she has collaborated on “A Christmas Carol,” adapted by Jesse Kornbluth, and “Blackie: The Horse Who Stood Still,” which she co-authored with Christopher Cerf. As a painter, she is represented by Gerald Peters Gallery in New York City and has been honored by The Guild Hall Academy of the Arts in East Hampton. She is a consultant to the Attitudinal Healing International organization and the Huntsman Cancer Foundation. Paige is the Author and Artist in Residence at Literacy Partners. As a photojournalist, Paige has reported extensively about the Middle East. She serves on the board of the National Council on U.S. Arab Relations, is an International Conservation Communication Specialist at Safari West, and Cheetah Conservation Fund Ambassador to the Middle East. Paige and her two grown children live in New York. Ms. Peterson splits her time between New York City and Belvedere, California.