“I’m getting awfully tired of this loneliness. It’s as bad as being in a state prison.”

— Amos Clift, Farallon Islands, lighthouse keeper, 1859

Not much has changed on the Farallones since lighthouse keeper Amos Clift’s time there. The islands are still a lonely place for humans (although seabirds find plenty of feathered company). But for the few who venture there, the isolation is more than offset by the wild beauty of the land and the dominance of nature.

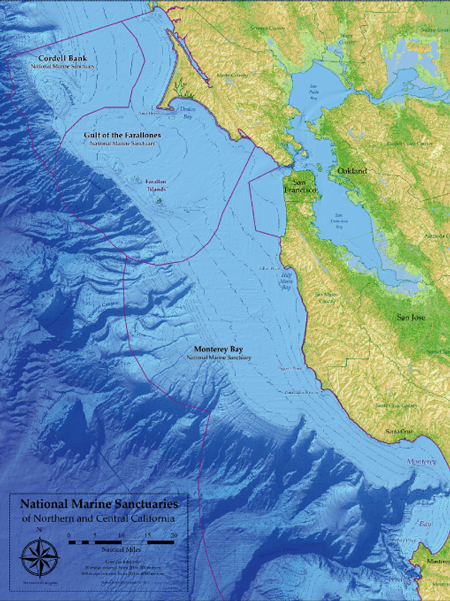

The Farallon Islands (or Farallones, in the Spanish plural form of the name) are a dozen or so brutish outcroppings of an undersea mountain range 20 miles south of Point Reyes and 27 miles west of the Golden Gate Bridge. Most of the islands are little more than exposed rocks. Case in point: Middle Farallon Island is so small it’s nicknamed “the Pimple.” Only 120-acre Southeast Farallon Island, rising more than 300 feet above the water, is considered habitable. The tiny archipelago is staggered along the edge of the continental shelf in waters that measure 300 feet deep but within a few miles plunge to depths of two miles and more.

Those lucky Marin residents who’ve been there say a calm day on the Farallones is when winds howl at only 30 knots and the waves crest at 15 feet. The sun shines, at best, only one in four days.

The islands were named by a Spanish explorer—farallon means “rocky promontory rising from the sea”—but local mariners, wary of the islands’ menacing appearance and of the dangerous shoals, refer to the Farallones as “the Devil’s Teeth.” Today, the biologists who work on the islands, studying teeming colonies of seabirds and ocean mammals, look on the land as more benign—a bounteous natural laboratory they call the “the Galapagos of California.”

From Drake to Theodore Roosevelt

Europeans discovered the Farallones 41 years before the Pilgrims landed at Plymouth Rock and nearly 200 years before the first European, Jose Francisco Ortega, saw San Francisco Bay. On July 23, 1579, Sir Francis Drake pulled anchor near Tomales Bay and was headed home via the Far East; the next day his ship, the Golden Hind, passed by the Farallones. Wanting seal meat and seabird eggs, Drake or possibly one of his crew was the first to set foot on Southeast Farallon Island. The islands got their name in 1603 from Spain’s Sebastian Vizcaino, the first explorer to chart “the rocks.”

In the ensuing years, hunters from first New England, then Russia were drawn to the Farallones, seeking the luxuriant pelts of the Northern fur seal, which they hunted nearly to extinction. During the Gold Rush, eggs from the islands’ birds fed the booming city of San Francisco. A thriving (and fractious) island industry existed for more than 25 years, at its peak removing half a million eggs a month.

In 1853, a lighthouse was built atop 348-foot-high Tower Hill on Southeast Farallon Island, and two stone homes for the lighthouse keepers and their families were constructed at the hill’s base. The lighthouse is now automated, but biologists still use the houses. In 1909, President Theodore Roosevelt created the Farallon National Reservation, which in 1969 became the Farallon Islands National Wildlife Refuge.

It was about this time that several Marin residents began playing a critical role in the Farallones’ fate.

San Francisco and the U.S. Government

Considering how remote the Farallones are—no more than eight people are allowed on Southeast Farallon Island at once—they hardly lack for governmental jurisdictions. The islands are actually located within the boundaries of the city of San Francisco. The surrounding water (300 feet beyond the mean high tide line) comprises the 1,281-square-mile Gulf of the Farallones National Marine Sanctuary, which includes Tomales Bay in Marin County. A supporting nonprofit organization, the Farallon Marine Sanctuary Association, maintains an informational center about the islands at San Francisco’s Crissy Field. “Short of a three-hour boat trip that often gets rough, this is as up close and personal as many will ever get to the Farallon Islands,” says sanctuary spokesperson and Corte Madera resident Mary Jane Schramm.

The islands are controlled by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, which contracts out biological research and caretaking operations to PRBO Conservation Science, a Petaluma nonprofit once known as Point Reyes Bird Observatory.

PRBO Conservation Science

“The Point Reyes Bird Observatory was founded in 1965,” explains PRBO Conservation Science president and CEO Ellie M. Cohen of San Anselmo. “Two years ago, due to a surge in demand for our services, we updated our name and moved into our 20,000-square-foot San Francisco Bay Research Center along the banks of the Shollenberger marsh in Petaluma.” The organization still operates its original Palomarin center a few miles outside Bolinas.

The organization examines the relationship between marine birds and mammals, develops “oiled bird” procedures in use throughout the world and establishes streamside habitats that protect breeding songbirds. “Although the Farallones are a primary focus, we’ve implemented research in areas as varied as Antarctica and California’s Central Valley,” says Cohen. The group’s annual $6.7 million budget supports a staff of 65 scientists, 55 seasonal biologists and 85 conservation interns, though not all funds and resources go to the Farallones.

PRBO Conservation Science has managed research and operations at the Farallones since 1968. “There are few places on earth where scientists can ask the kinds of questions about environmental change that PRBO addresses out on the Farallones,” says Cohen. December through March, research focuses on northern elephant seals; April through August, mostly on seabirds; and September through November, on migratory songbirds and great white sharks.

The Farallones are home to a quarter of a million seabirds, including common murres, western gulls, Brandt’s cormorants, tufted puffins and Cassin’s auklets, and thousands of pinnipeds, such as California and steller sea lions, northern elephant seals and the once nearly extinct Northern fur seal. The surrounding waters are populated by whales (Blue, Humpback and Orca), porpoises (Harbor and Dall’s), dolphins (White-sided and Risso’s) and, in the fall, an estimated two dozen great white sharks. For the past 40 years, Farallon researchers have logged their daily wildlife sightings into a carefully maintained journal.

Farallon images by Zachary Coffman. Image 1: View from the sea when approaching the islands.

Image 2: Basking sea lions are a common sight on the rocky shores of the Farallones.

Marin Volunteers

Henry Corning made the first of many trips to the Farallones in 1978. “It started with a bunch of seagoing volunteers we called the Farallon Patrol,” says the Corte Madera venture capitalist. “We ferried biologists and their supplies out to the islands.” Corning figures he’s made the three-hour trip to the islands more than 150 times. In 1990, after he’d begun a life partnership with artist Glenda Griffith, the couple’s collaborative studio, Meadowsweet Dairy, spent more than a year designing, permitting and assembling For the Birds, a nesting habitat they refer to as “environmental art.”

“We worked with Fish and Wildlife Services and PRBO and it was funded by the Haas Creative Work Fund,” Griffith says. “We built a stainless steel framework that had to be helicoptered out to the Southeast Farallon Island.” Once secured to an existing concrete foundation, the frame was covered in rubble to look as natural as possible. “A small door allows biologists to go inside the habitat,” says Corning, “and, in a non-threatening way, monitor the [nesting] process.” Within months several species were nesting inside the structure.

More recently, Corning and Griffith created a 50-square-foot wood-framed, copper-covered biologist’s observation hut that soon took on a green moss-like patina. “The settlement from a Southern California oil spill funded this one,” says Griffith, 51, who’s made more than 40 trips to the Farallones. “And again, it’s both functional and artistic,” says Corning, 64, “with a carefully chosen location. Biologists can observe the Common murre close up in its island setting and the birds don’t feel threatened.”

Working with Corning and Griffith on this second environmental art installation was Bolinas stonemason Charles Whitefield, 50, whom Griffith describes as a “godsend to the islands.” Whitefield’s current project is restoring the historic rock trail leading from the stone houses up to the lighthouse. “It’s a quarter of a mile long and has to be rebuilt so that it encourages birds to nest in it,” he says. That is no small task because, in order to protect the delicate environment, the trail, built originally in the early 1850s, had to be reconstructed without using concrete. “Researchers will use [the trail] daily in the fall to monitor great white shark attacks on Elephant seals,” Whitefield adds. “Also, chinks have to be left in the retaining wall so the Ashy storm-petrel and Brandt’s cormorant will nest there.”

Despite the hardships of working on the islands—after the stomach-turning boat ride, visitors are treated to a 30-foot crane ride in order even to get onto Southeast Farallon Island, where they face routine water shortages and a steady diet of lousy weather—Whitefield says he’s “stoked” every time he’s there. “It’s a whole other world, in a whole other century,” he says. “In every way, it’s just beautiful.”

That raw beauty is what draws Marjorie Siegel of Mill Valley to work as a volunteer on the Farallones. Since 1993, Siegel has been visiting the islands every chance she gets and doing whatever work is given her. “I always wanted to go out there,” she says. Over a three-day stay in 2002, she helped biologists inventory the bird population. “We pretty much verified there are 250,000 birds and a dozen different species,” she says.

“She’s delightful,” sanctuary spokesperson Schramm says of Siegel. “She’s as meticulous as a scientist, without the ego that’s often part of the package.”

“She’s delightful,” sanctuary spokesperson Schramm says of Siegel. “She’s as meticulous as a scientist, without the ego that’s often part of the package.”

In 2006, Siegel and two other volunteers, working for the USFWS, eradicated a patch of New Zealand spinach, an invasive weed that had found its way onto the island and was taking over several nesting habitats. “That was a two-week stay,” she says, “and the camaraderie among those working out there was so great I wanted to stay longer.”

At times, Siegel admits, life on the Farallones can bring on a bit of claustrophobia: “Knowing you don’t control how or when you’ll get off the island can be an issue.” But that unease quickly disappears in the natural wonder of the place. “On a clear night, off in the distance you can see city lights and you feel like you’re on a different planet. It’s magical. When you’re on the Farallones, you’re in a place where nature dominates.”

Image 3: For the Birds, a nesting habitat designed and assembled by Henry Corning and Glenda Griffith of Corte Madera

Image 4: (Photos by Tim Porter) From Left: Venture captialist Henry Corning, artist Glenda Griffith, Bolinas stonemason Charles Whitefiled, Mill Valley volunteer Marjorie Siegel