IT’S NO SURPRISE THAT theological seminaries have lately fallen on hard times. Enrollment is down at many of these institutions, especially in California, where an increasingly secular society places less value on religious education that it once did. As a result, many seminaries face the possibility of soon having to close their doors.

The San Francisco Theological Seminary, in San Anselmo in the shadow of Mount Tamalpais, is no exception in that trend. This Presbyterian seminary has occupied a lovely, tree-shaded campus on the eastern edge of town since 1890, when it moved there from its original location in San Francisco. But SFTS, as it’s often called, has decided to face its challenges head-on. Its directors have devised a plan of action to both keep their institution open and make its programs more relevant to 21st-century theology.

In July 2019, SFTS announced it had completed a merger with the University of Redlands in Southern California. This merger will create the new Graduate School of Theology at the University of Redlands and still allow the San Anselmo location to continue offering degrees in theology and related fields. The deal also allows SFTS to preserve the beauty of the San Anselmo site’s many historic buildings and ensure they can keep serving the purposes for which they were designed. The buildings here are an impressive example of late 19th- and early 20th-century architecture, including two structures by Julia Morgan.

Visitors to the campus of the San Francisco Theological Seminary often remark that the setting reminds them of a small private college on the East Coast or in the Midwest. Indeed, this campus contains one of the few collections of Richardsonian Romanesque Revival architecture in California. That style, created by H.H. Richardson in the 1870s, debuted in the design of Trinity Church in Boston in 1877 and soon became popular for religious buildings east of the Mississippi River, although less so for structures in the West. In California, one reason for its scarcity was that it employed rusticated stone walls in imitation of medieval European churches, which was seen as risky in earthquake country. The 1868 Hollister earthquake in the East Bay had done major damage to churches in then-sparsely populated Alameda County. Yet memories of that devastation had faded by the time the San Francisco Theological Seminary moved to its Marin campus in 1892.

When SFTS opened in San Francisco in 1871, it had four professors and four students, who met for classes at Presbyterian City College in Union Square. Six years later the seminary moved to a new building next to City College on Haight Street. Seeking a location with a more “salubrious air,” in its directors’ words, it moved to its current 24-acre campus on a hilltop in San Anselmo. Marin railroad owner and banker Arthur W. Foster donated the land in 1889 (originally 19 acres; more were donated later). Later that year, San Francisco financier and philanthropist Alexander Montgomery provided a $250,000 endowment for the building fund and $100,000 for faculty salaries.

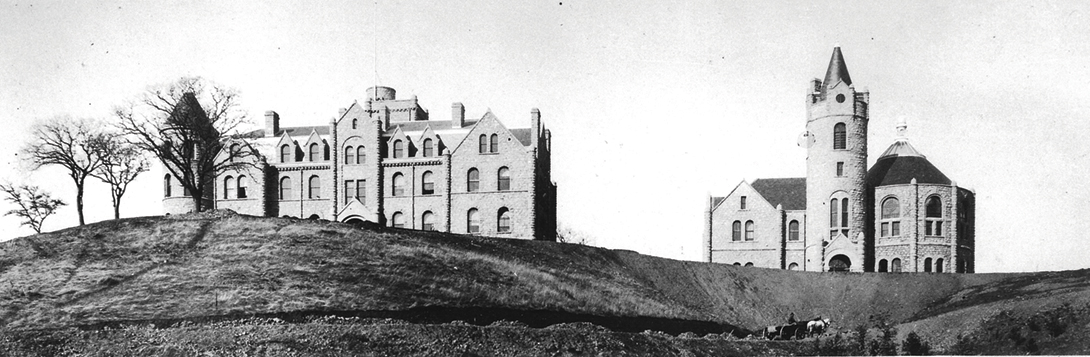

The first two buildings on the new campus were in the Romanesque Revival style: Montgomery Hall, named after benefactor Montgomery, and Scott Hall, named for Mrs. A.W. Foster, daughter of SFTS founder William A. Scott. Both buildings were dedicated on September 21, 1892, when opening exercises were held. Montgomery Hall was originally the student dormitory and now houses faculty and administration offices. It was designed by the San Francisco architectural firm Wright and Sanders, as was Scott Hall, which originally contained a library, auditorium and classrooms and now also holds the student lounge.

Montgomery Chapel, as yet another Richardsonian Romanesque campus architectural gem, was also designed by Wright and Sanders; construction began in 1894, was completed in 1897 and was funded by namesake Alexander Montgomery with a $40,000 donation. The chapel served as the campus’s First Presbyterian church until the late 1950s; today, religious services, as well as seminars and small classes, are still held there. With its round corner bell tower topped by a conical spire and cast-iron weather vane, thick rusticated stone walls, and wide rotunda, this is perhaps the purest example of Romanesque Revival architecture in the state. A loggia lined with Romanesque arches and squat columns connects the chapel to adjoining Montague Hall, also Romanesque in style, which serves as a reception and meeting space.

Julia Morgan, America’s first independent licensed female architect, designed three buildings for the San Francisco Theological Seminary campus in the 1920s. The first one was intended to be a large dining hall, for which she produced a full set of blueprints. That structure was never built; instead San Anselmo architect J. Harold Osborn in 1928 designed the more modest brown-shingled Playhouse, which still stands on that site. In 1921 Morgan completed design for two residences on campus, one each for faculty and administrators.

Montgomery Hall. Photo by Fiona Lanham.

The larger of these is the President’s House, at 47 Seminary Road. This three-story brown-shingled house is a skillful blend of Arts and Crafts and Prairie styles. The facade presents a long horizontal mass, with a low-angled roofline and minimal ornamentation. In the center of the third story is a wide overhanging pavilion with a Palladian-style window; on either end of this story are latticed casement windows. Across the road, at 118 Bolinas Way, is the Dean’s House, originally designed as faculty housing. This two-story brown-shingled residence is in the Prairie Style, with Bay Tradition overtones. The horizontal massing, low-sloping roofline, and banded windows are Prairie features, while the unpainted shingled facade and flower box across the middle of the second story are Bay Tradition touches. Morgan also worked with Donald McLaren, son of John McLaren, who designed Golden Gate Park, on a landscaping master plan in 1921, most of which was never realized.

The last building on campus designed in a historic style was the neo-Gothic Geneva Hall, completed in 1952. The Santa Barbara firm of Soule and Murphy modeled it after a 13th-century Franciscan monastery in Assisi, Italy. It’s one of the largest buildings at SFTS, and its 100-foot- tall white stone tower dominates the campus. This multi-use structure includes a six-story library, a student resource center and the Stewart Memorial Chapel. The seminary’s main worship space, with seating for 200 people, was named after Mary Hurt Stewart, the second wife of one of the seminary’s first elders, who donated half her estate to pay for the chapel. The nave, with its massive dark-oak Gothic arches, light-oak back altar decorated with a scene from “The Last Supper” and iridescent stained-glass windows, creates an authentic Gothic ambience. The 50-foot ceilings, coffered paneling along the lower walls and huge organ in the organ loft complete the effect.

Surprisingly, the 1906 San Francisco earthquake did only moderate damage to the buildings on the SFTS campus. The tower of Scott Hall suffered the most serious impact, necessitating removal of its top 20 feet. All the masonry buildings on campus were earthquake retrofitted in the early 2000s.

Jana Childers, dean of SFTS and VP for Academic Affairs, has been teaching at the seminary since 1985 and has a Ph.D. in homiletics (the academic study of preaching) from the Graduate Theological Union in Berkeley. She describes the dilemma seminaries are facing in both numerical and cultural terms: the current student enrollment is 200, down from 500 students 15 years ago. Last year there were only 39 graduates. However, the student body has grown more diverse in recent years — 50 percent are people of color and 50 percent are female — as has the faculty: 60 percent people of color, two-thirds female. The current tuition is $18,000 per year, and grants are offered on a need and merit basis. After the merger with University of Redlands, the seminary will offer dual degrees, including MBAs and MSOLs (master of science in organizational leadership). “Many of our graduates go on to create their own nonprofits, like ministering to immigrants from Vietnam and Cambodia in the Sacramento area,” Childers says.

She is intent on ensuring that the seminary remains relevant to American society and the issues it faces today. Several years ago, facing declining enrollment and diminishing interest in studying for the ministry among young people, SFTS leaders recognized they had to come up with a creative solution. So they formed an exploratory committee and talked to several graduate schools about a merger, finally settling on Redlands. As a result, SFTS will now become a graduate school within the University of Redlands, and students from both schools can take classes on either campus.

According to Chris Ocker, professor of church history at SFTS, the seminary’s curriculum originally had a rigorous classical focus, with instruction in Latin and ancient Greek. Would-be pastors were trained to fit the traditional idea of what a Presbyterian clergy member should be, a much more limited role than current pastors are called on to per- form. “Women were only trained to be educators and missionaries at that time,” Ocker adds.

A documentary about SFTS, narrated by actor Jimmy Stewart in 1963, was made at a time when these traditional values still held sway. Another media figure associated with SFTS, Bernard Mayes, was a broadcaster and programmer at the SFTS student radio station in the mid-1960s, Ocker says — and sale of that station’s transmitter led to the formation of KQED-FM in 1969. Mayes went on to become the first general manager of NPR in the 1970s. Also, Robert Sproul, former chancellor of the University of California and namesake of Sproul Hall on the UC Berkeley campus, was on the board of directors of the SFTS student radio station during the 1940s.

“What’s unusual about SFTS is that we’re able to hold spirituality and social justice together,” Childers says. “And we have a passionate commitment to innovation. As churches change, we want to be on the cutting edge of what’s next, so we can address both the needs of rural poverty and the unique challenges of urban ministry. We’re working to expand our ministries of justice, peace and healing to meet the demands of the 21st century.”

As the San Francisco Theological Seminary prepares to celebrate its 150th anniversary next year, it seems to be on a path to honor its past and look with confidence and energy toward the future.

This article was prepared with information provided by SFTS’s Stephanie Miller, branch librarian, and Liz Huntington, VP of marketing and communications