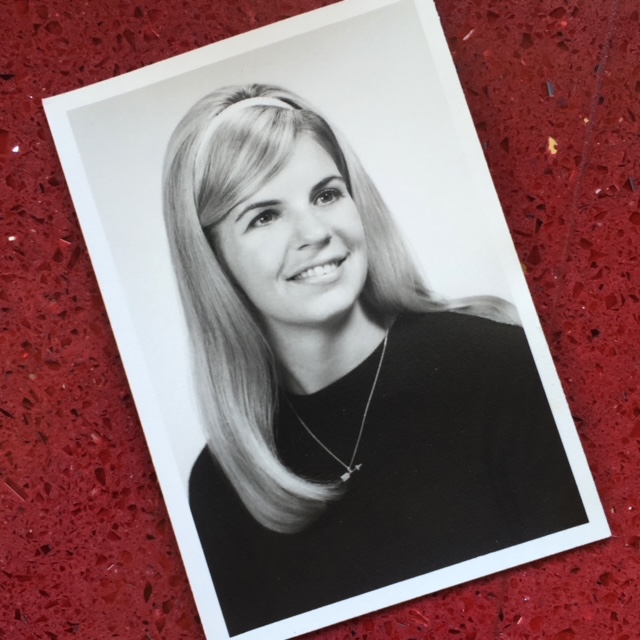

Although she has lived in Tiburon for over half a century, Lee Darby still fondly remembers her childhood growing up in Menlo Park – not just because it was idyllic, but because it carries cherished memories of her younger sister, Sally Voye. “Sally and I were only one year apart, so we did everything together — Girl Scouts, riding our bikes to school, all of that,” she says. These recollections make up the start of Darby’s recently published book, Stars in Our Eyes, 40 years in the making, which recounts her sister’s life and attempts to unravel the series of complicated events leading up to her death.

A Desire to Make a Difference

Darby and Voye came of age in the mid-1970s. While the Bay Area famously gave rise to the hippie movement in the 1960s, with its rejection of violence and peaceful protests, in the 1970s, counterculture had evolved into more radical forms of resistance. The Bay Area was ruled by political groups, many of which originated out of San Quentin State Prison — groups battling against racism, the status quo and sometimes, with each other. The most famous of them was the Symbionese Liberation Army (SLA), the group that kidnapped Patty Hearst about a year before Voye was killed.

Darby recalls her sister as being idealistic and wildly passionate about making a difference. The San Francisco Chronicle would later publish a description of her from a roommate at UC Santa Barbara: “She was sort of a not-political idealist, a good person — the kind more of us should be like.” Voye went on to get a teaching credential from UC Berkeley, and as soon as she graduated, she began volunteering with a literacy program at San Quentin. “When she went to Berkeley things kind of changed,” Darby says. “She became aware that she was a privileged person, and she wanted to help the disadvantaged.”

This experience would change Voye’s life. At San Quentin she met the leader of the United Prisoner’s Union, Wilbert “Popeye” Jackson. “Popeye wanted to improve the conditions at the prison, including better food, better medical care and better visitor facilities,” Darby explains. But he was involved in a lot more than that.

Wilbert “Popeye” Jackson, and the Kidnapping of Patty Hearst

Although Popeye had spent much of his life in jail when he met Voye, he had been out of prison for a few years and was expecting a child. According to the San Francisco Chronicle, Popeye’s jail sentences seemed to be for minor infractions, writing: “He was arrested on charges of heroin and marijuana possession… but was acquitted after a jury trial… he was again arrested on a misdemeanor charge of ‘interfering with a police officer in the performance of his duty.’”

While researching her book, Darby spent time trying to uncover more about her sister’s relationship with the prison activist. “I began to see what must have drawn Sally to him when I read that in April 1974, the ‘charismatic’ Popeye went to a parole hearing at San Quentin and ‘150 supporters marched in the rain’ outside the prison walls… he could draw a crowd, he had charisma… he had achieved a certain status.”

The United Prisoner’s Union that Popeye headed up had been associated with George Jackson, a former inmate at San Quentin, also a Black Panther and one of the Soledad Brothers, famous for their 1970 uprising against the conditions at Soledad State Prison. George’s brother Jonathan Jackson would later storm the Marin County Civic Center in an attempt to secure his brother’s release, an incident also connected with Angela Davis, the legendary activist who is a professor at UC Santa Cruz.

In 1974, Popeye was instrumental in the negotiations that took place in the Patty Hearst kidnapping by the Symbionese Liberation Army. Following Patty’s capture, the SLA demanded a $4 million ransom to be paid in the form of a food program benefiting the Bay Area’s poor, called The People in Need program. Patty’s father, Randolph Hearst, the chairman of the board at Hearst, which owned the San Francisco Examiner, needed a liaison during the negotiation process. The negotiations were being handled by the FBI and the San Francisco Police Department, but the SLA wanted nothing to do with the authorities, so to orchestrate the negotiations they relied on Popeye, who was an influential member of the coalition of groups organizing the giveaways, and had managed to create a rapport with the newspaper magnate.

The People in Need program was a massive undertaking that involved distributing food to people across the Bay Area. A woman named Sarah Jane Moore was put in charge of setting up distribution centers in San Francisco and Oakland. “She made a mess of it,” Darby explains. “It was chaos at the giveaway stations: People were running off with the money and overinflating prices, and many were getting mugged.”

Then things truly began to unravel. A radical herself and rumored informant, Moore became unhinged. Less than three weeks before, a follower of Charles Manson had attempted to shoot President Gerald Ford when he visited Sacramento. Now, when the president arrived in Union Square to give a speech, Moore decided to make her own assassination attempt, which was thwarted when a bystander tackled her. When she was asked later why she did this, her answer was, “well, everyone was talking about it.”

A Tragedy in the Mission

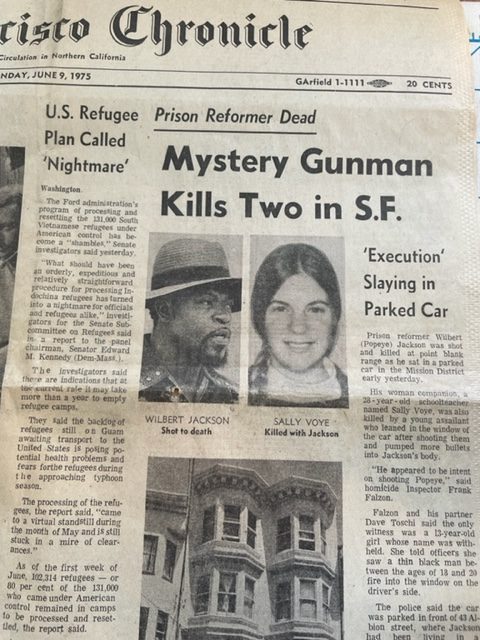

It was in this climate that Voye volunteered at San Quentin. On June 8, 1975, she drove Popeye home from a fundraising party. The car was parked on a small side street in the Mission District in San Francisco. “They were sitting in her car chatting in front of his apartment on Albion Street and someone came up and just emptied their gun,” Darby says.

What happened next was a media frenzy. It eventually came to light that the hit was ordered by a rival gang, Tribal Thumb, though the motivations weren’t entirely clear. Rumors flew and rival gangs made different claims about why the hit happened.

The SLA even put out a statement in support of Popeye after his death: “We have long considered Popeye to be a friend and comrade. We support his work in the prison movement and his outspoken stance in supporting guerrilla fighters.”

A flurry of contradictory stories surfaced in the papers in the following weeks. First, the New World Liberation Front claimed responsibility, then, according to an article in The New York Times, they claimed that they didn’t, as, “A few days before the killing, the New World group purportedly sent a letter to a local radio station attacking Mr. Jackson… for wearing flamboyant clothes and driving a Cadillac and hinted that he was a police informer.”

Other rumors claimed there were actually two shooters, that the Aryan Brotherhood was responsible and, most importantly, that Voye could have herself been an informant — an article in Playboy even made this accusation. Darby empathetically denies this, and says disproving the allegation was part of what inspired her write her book. “There was no way she was an informant,” Darby says. “She was trying to help to help rehabilitate people. The United Prisoners Union’s focus was to improve conditions at the prison.”

Darby’s theory as to what happened is that the rival group, Tribal Thumb, was unhappy because Popeye got all the press attention. “There were many different groups at the time,” she explains. “All these people weighed in on it — first they would say they were snitches, and then somebody else said they weren’t snitches. Every day there was something new in the newspaper, and it was it was really upsetting. We were beyond horrified that that her name was being dragged through the mud.”

Honoring Her Sister’s Memory

Voye was passionate about her social work. Having grown up during the Civil Rights movement of the 1960s, she was particularly committed to helping the Black community. “I remember when she was still in Berkeley and she got burgled and called me up in tears,” Darby says. “She was just furious, but not at the burglars — I think there were two Black youths that were seen running down her driveway — but that the government couldn’t do enough to help Black people. Today, she would certainly be carrying a Black Lives Matter placard. She would be pleased at the progress that’s been made, but there’s still a long way to go.”

Darby wrote Star in our Eyes to honor the memory of her sister, who believed so strongly in equality. Years after the incident, Darby gave back in her own small way by working at San Quentin prison. “I felt like I played a small role in in furthering her goals,” she says. “I was a construction manager on a five-story $30 million healthcare facility built there, which included medical, mental health and dental care. It just kind of closed that circle. I still wonder if she would have thought that was enough.” Darby answers her own question in her book. “[She would have wanted] better food, more childcare, improved visitor areas, a solution to overcrowding… I think I know the answer because I know the truth. She wanted to make a difference.”

Jessica Gliddon is the Group Digital Content Manager for Marin Magazine. An international writer and editor, she has worked on publications in the UK, Dubai and Cape Town. She is a graduate of UC Santa Cruz, and is the former editor of Abu Dhabi’s airline magazine, Etihad Inflight. When she’s not checking out the latest exhibit at SFMOMA or searching out the best places to eat and drink near her home in San Francisco, she volunteers at the Marine Mammal Center in Sausalito.