Ever feel grateful that Stinson Beach is a pristine natural coastal park rather than a Coney Island–style boardwalk? Ever notice how Marin’s central throughway, Highway 101, offers wideopen views of Richardson Bay, Mount Tamalpais and Big Rock Ridge, unmarred by ugly billboards? And have you hiked, biked or camped overnight on Angel Island and wondered how we Marinites got so lucky? Well, it was not luck that made it Marin County what it is today. It was badass women.

From a leading suffragist, who organized in Marin and then went to Washington to secure women’s right to vote, to a colorful madam turned Sausalito mayor (at age 72) who hated bureaucracy and championed law enforcement. From one of the state’s first female undertakers to a renowned female blacksmith (both suffragists) to the county’s first female supervisor, who would not take no for an answer and got her male counterparts to approve the Frank Lloyd Wright–designed building that would become an architectural treasure, Marin history is a tale of determined women, some born into privilege, some scrappy bootstrappers, who had a particularly effective combination of moxie and vision.

Yet today, even as we enjoy the fruits of their fearlessness, most of us do not know their names or the details of the battles they waged. In the words of Marin County Library’s California Room digital historian Carol Acquaviva, “There are so many women, midcentury and before, who did a tremendous amount of important work here in Marin, but they didn’t get credit because they were only referred to as ‘Mrs. so and so.’ ”

The Environmentalists

A STONE’S THROW from a major metropolitan area, Marin remains one of the most picturesque counties in the world, defined by stretches of undeveloped coastal beaches, rolling green hills and ridges, and uninterrupted views of both San Francisco Bay and the Pacific. This is not by accident.

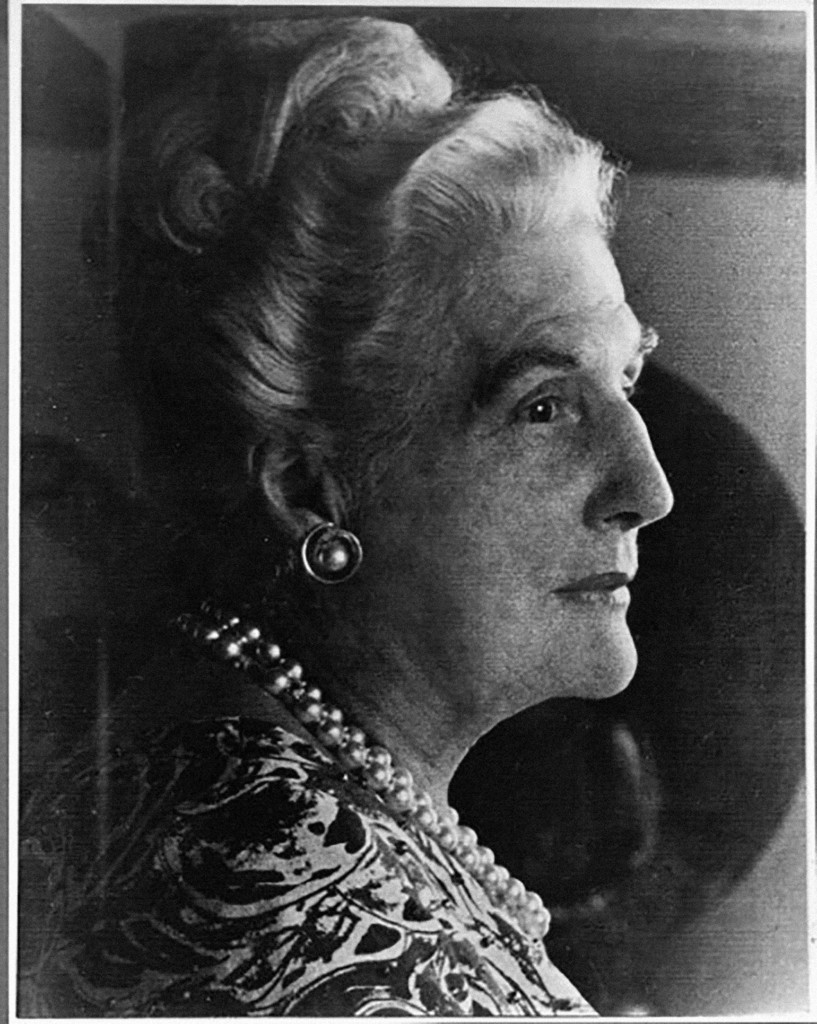

In the mid-1930s, Caroline Sealy Livermore was living in a large home on several acres on Canyon Road in Ross. Originally from Texas, Livermore was Vassar College educated and then raised five sons in San Francisco and Marin with her businessman husband, Norman Livermore. She was a woman of means and could easily have been a woman of leisure, but that was not her way. According to Vicki Nichols, a board member and historian for the Marin Conservation League, which Livermore founded, her nature was to organize people and get things done. And Livermore’s singular goal was to preserve the natural world and make it accessible to all. “Caroline Livermore could have been doing more frivolous things. She didn’t have to work, but she made it her mission to preserve and increase beauty — to support the arts and to save land so that anyone of any income could have access, for the civic good and for future generations,” Nichols says.

In the 1930s, most communities did not have an orientation toward urban planning, but across the nation a “beautification” movement was growing, and it captured Livermore’s attention. She traveled cross-country to gather information and inspiration. As Nichols found in researching archival documents about Livermore’s life, on November 5, 1934, Livermore attended a Marin Garden Club meeting and brought up the impending opening of the Golden Gate Bridge (it would open in 1937). She pointed out that there would be an increase in car traffic to bucolic Marin. “‘We need to do something,’ she told the club. ‘OK, Caroline, you form the committee,’ the Garden Club members told her. So that is exactly what she did,” Nichols says.

Livermore teamed with club members Sepha Evers, Portia Forbes and Helen Van Pelt. They were concerned that Marin would become a county of sprawl like Los Angeles or of cheap tourist development like Coney Island. According to Sepha Evers’s son Bill Evers, the team was constantly on the telephone, working relentlessly to create county and state parks. They raised seed money and pressured the county to match their efforts to establish what we know today as Samuel P. Taylor State Park, Tomales Bay, Stinson Beach and Angel Island, whose single peak, Mount Caroline Livermore, has the conservation maven’s name.

Livermore was known as a “nodder,” says Nichols. It is said she would attend Marin County Board of Supervisor meetings and sit in the front row in a big hat. If she liked what was happening, she would conspicuously nod her approval. If she did not approve, she would shake her head. Her presence felt by all, Livermore was able to get a historic local zoning ordinance passed to remove what she called “ugly roadside billboards” in Marin County.

The Suffragists

TODAY MORE WOMEN cast their votes in state and national elections than men do, so it is hard to imagine that just a century ago women were not allowed to vote in this country. California was the sixth state to pass women’s suffrage laws (Proposition 4, in 1911, nine years before the national Suffrage Amendment became law in 1920), and we can trace the suffrage movement’s roots and progress to some key Marin County women.

In the early 1900s few women had professional careers, and even fewer owned businesses. As recounted in research by oral historian and writer Marily Geary, Mill Valley resident Lillian Harris Coffin, an undertaker, understood that founding a women-owned-and-operated business would advance the suffrage cause, proving a woman’s capability and capacity to participate and lead in the economy. In 1908, Coffin, then president of the Equal Suffrage League of San Francisco, formed the California Woman’s Undertaking Company, the first such business run entirely by women in California. Around the same time, two other Marin women also forged their way into male-dominated businesses. Lillian McNeill Palmer, a blacksmith, became a renowned metalworker, and Palmer’s lifelong partner, Emily Eolian Williams, started her own architecture firm and became one of the first female architects in Northern California. Geary cites the Mill Valley Record of September 1, 1911, which described Palmer speaking at an event on a dance platform across from the Mill Valley Depot as “the first move of the local suffragists to coax the men of Mill Valley to their side.”

Palmer and Williams were contemporaries and fellow suffrage activists with another couple, Lillian O’Hara and Grace Livermore (no relation to Caroline Livermore), who owned a summer property in San Anselmo. According to Geary, O’Hara and Livermore hosted a suffrage fundraising party in the fall before the October vote on Proposition 4 and the Mill Valley Record reported that on Sept 7, 1911, “a big four-horse bus, decorated in the yellow suffrage color” took paying guests up to O’Hara and Livermore’s garden enclave. Archival campaign slogans from the time that made clear the suffragists’ demands: “For the Long Work Day/For the Taxes We Pay/For the Laws We Obey/We Want Something to Say!” For Geary, researching the activities of these early Marin County women truly brought home the challenges they faced. “It really struck me that they had no agency,” she says. “They got together and organized, but then had to get the men to vote. Imagine if you felt strongly about something, but if you wanted anything to get done you had to do it through your husband or brother or father.”

According to the San Francisco Call of April 10, 1911, while the garden parties were happening in San Anselmo, Elizabeth Thacher Kent, a philanthropist, activist and mother of seven from Kentfield, was organizing “prominent members of the Ross and San Rafael smart set” at the Tamalpais Club, where “men well-known in business and social circles urged [in favor of] the right of women to vote.” After women’s suffrage became law in California, Kent moved with her husband, Congressman William Kent, to Washington, D.C., where she became a leader in the national women’s suffrage movement. In a speech before the House of Representatives in 1912, Kent said, “[Abraham] Lincoln believed in government by the people. Women are people. We want to be recognized as people; we want our share of responsibility in the government under which we live.”

Laurie Thompson is librarian and historian at the Anne T. Kent California Room of the Marin County Free Library and greatly admires Kent ’s approach to activism. “Elizabeth Thacher Kent was diplomatic and did things in a way where she didn’t burn bridges,” Thompson says. “And at the same time, she was strong and highly principled.” Kent, Thompson says, was arrested twice while demonstrating with other members of the National Woman’s Party at protests in front of the White House. She publicly opposed Woodrow Wilson, who at first was against women’s suffrage, even as her politician husband was campaigning for Wilson’s reelection. “That took courage,” says Nichols. “Even today that would take courage.” From 1912 to 1919, Kent gave speeches, testified before Congress and worked on suffrage campaigns in 15 states, until finally, on August 18, 1920, the 19th amendment was ratified.

The Politicians

WHILE LIVERMORE, KENT and other local activists came from wealthy families and were highly educated, other Marin County women rose from poverty and established themselves as local leaders and visionaries, paving the way for future generations of female politicians. Sally Stanford (nОe Mabel Janice Busby) was born in Baker City, Oregon, in 1903. In her autobiography The Lady of the House, she says she only attended school through the third grade. When her father died, she was responsible for bringing in money to support her mother and her four siblings, so she took odd jobs, such as caddying on a golf course. At 16, she eloped and began a life on the wrong side of the law, primarily as a bootlegger during Prohibition. Arrested 17 times over the course of 25 years, she noted she was only found guilty twice.

A larger-than-life character known for sass, wit and a sharp tongue, Stanford landed in Nob Hill in 1924, invested the money she’d made bootlegging in real estate, and soon became San Francisco’s most successful madam, at one point running 12 different bordellos. By 1949, amid a climate of increased harassment by local police and District Attorney Pat Brown, Stanford decided she needed a change of venue and moved to Sausalito, where she purchased the waterfront Valhalla Inn. A shrewd businesswoman and marketer, she drew celebrities like Marlon Brando, Bing Crosby and Lucille Ball to her restaurant. Although Valhalla was purportedly only a fine dining establishment, a red light over the back door indicated otherwise. Stanford evolved as she aged, becoming more and more interested in civic engagement. She ran unsuccessfully for Sausalito City Council five times — her platform promoted public toilets and increased funds for law enforcement — until she was finally elected the sixth time, in 1972. Three years later, at 72, she became mayor. Despite her historically adversarial relationship with the police, Stanford earned a reputation as a pro-law-enforcement leader. At one point during her tenure, local historian Vicki Nichols says, there were women soliciting by the old bait shop in Sausalito, and Stanford had to send the police to round them up; “that was one of the hardest things I’ve ever had to do,” Stanford later remarked. She was also known as a compulsively charitable person who picked up the restaurant tab for veterans or paid for funerals of the homeless.

As Stanford made her mark in Sausalito, her contemporary, Vera Schultz, gained notoriety for becoming the first woman elected to the Marin County Board of Supervisors and the first female supervisor in Northern California in 1952. Born Vera Lucille Smith in 1902, she was the youngest of eight children and grew up in Tonopah, Nevada and Dutch Flats, California, according to Marin Historical Society documents and the biography Vera Schultz, First Lady of Marin. Like Stanford, she lost her father early in life. She helped her mother run a boardinghouse and read voraciously, raised money for her own piano lessons, and found her way to University of Nevada, Reno, where she studied journalism and became editor of the campus newspaper. In 1926, she married Norman Schultz but kept the marriage a secret so she could keep her reporting job with the Oakland Post-Enquirer, a Hearst newspaper (Hearst would not employ married women).

The couple moved to Mill Valley in 1928 and Schultz took a position as assistant to the Superintendent of Schools. She became active in Democratic politics and was the first woman elected to the Mill Valley City Council, beating six male contenders with 86 percent of the vote in 1946. She told the Marin Independent Journal that this landslide should have made her the de facto mayor, but the men would not allow it. In 1952, she won a seat as the first female on the Marin County Board of Supervisors, but encountered great resistance from the “Courthouse Gang,” the existing male guard of supervisors known for their pork barrel politics. At her first North Coast Counties Association of Supervisors meeting someone posted a “No Women Allowed” sign, and it was suggested she attend the wives’ fashion luncheon instead. She tore the sign up and took her place at the meeting.

Schultz was a proponent of service and social reform in government, Nichols says, advocating affordable housing developments and racial integration at a time when entrenched politicians looked to sell off land for profit and regularly reaped spoils. She had no problem fighting for her vision, and she would publicly embarrass her counterparts for their corruption. Among dozens of accomplishments that helped to create the county as we know it today, she established the Marin County Parks and Recreation Department, the Public Works Department, the County Personnel Commission and the Public Health Department. She spearheaded the opening of Marin’s first school for disabled children, helped establish the Meals on Wheels program and championed the purchase of military land to build Marin City, with a dream of creating a racially integrated low- and middle-income housing project.

In 1957, Schultz proposed that Frank Lloyd Wright, the most prominent architect of the era, design the new Marin County Civic Center and Courthouse complex, to be built on ranch property just north of San Rafael. Schultz’s opponents on the Board of Supervisors publicly accused Wright of being a Communist, which prompted the architect to storm out of the meeting held to approve his plan. But Schultz would not back down; she shamed Wright’s accusers and, in the end, brought him back into contract to design what has become Marin County’s iconic architectural landmark.

Marin, the physical setting and the quality of life we all share today, would not exist if not for the legacy of these fierce women. “We have so many things to thank them for,” historian Marilyn Geary says. Archival newspaper articles reveal the general disdain that male contemporaries, including newspaper reporters, had for such women, especially suffragists, who were seen as immoral; today it is hard to imagine how determined they had to be and the societal laws and obstacles they overcame to accomplish their goals. “These women are heroes, each of them,” Marin Conservation League’s Nichols says. “And it is empowering for everybody who lives in Marin to know who they were.”

How to Help

For more ways to support local businesses, go here.

For more on Marin:

- Home Meal Delivery Services for Bay Area Residents Sheltering in Place

- To Surf or Not To Surf? And How to Be a Sustainable Surfer?

- My So-Called Shelter-in-Place Life

Kirsten Jones Neff is a journalist who writes about all things North Bay, with special attention to the environment and the region’s farmers, winemakers and food artisans. She also works and teaches in school gardens. Kirsten’s poetry collection, When The House Is Quiet, was nominated for the Northern California Book Award, and three of her poems received a Pushcart nomination. She lives in Novato with her husband and three children and tries to spend as much time as possible on our local mountains, beaches and waterways. For more on her work visit KirstenJonesNeff.com.

Kirsten Jones Neff is a journalist who writes about all things North Bay, with special attention to the environment and the region’s farmers, winemakers and food artisans. She also works and teaches in school gardens. Kirsten’s poetry collection, When The House Is Quiet, was nominated for the Northern California Book Award, and three of her poems received a Pushcart nomination. She lives in Novato with her husband and three children and tries to spend as much time as possible on our local mountains, beaches and waterways. For more on her work visit KirstenJonesNeff.com.