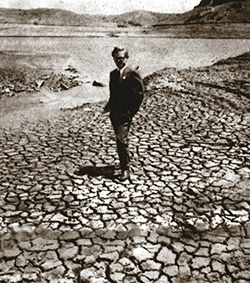

“For a while there, I honestly thought we’d be bringing water to Marin County in tanker trucks,” recalls J. Dietrich “Diet” Stroeh, “and people would line up with their buckets, like they do in Africa or India.”

Times never got that desperate, but it was close. It was 35 years ago, from the spring of 1975 through winter of 1977, when little rain fell in Marin—and Diet Stroeh, cofounder of the Novato civil engineering firm CSW/Stuber Stroeh, was general manager of the Marin Municipal Water District (MMWD). “Many people blamed me. I thought I’d be run out of town,” he says now. “At best, that I’d lose my job and my career would be ruined.”

As it turned out, Stroeh has been hailed as a hero ever since. But for two years, waterwise in Marin, things were touch and go. Three factors contributed to the crisis. Early on, the county did not join Sonoma County’s Russian River system; instead, it relied on rain falling on the Mount Tamalpais and West Marin watersheds to keep its then-six reservoirs sufficiently full. Then, in the early 1970s, led by community activist Barbara Boxer, Marin voters soundly defeated Measure E, a plan to import Russian River water to augment the county’s reservoir system. And finally, it wasn’t that it didn’t rain at all during the winters of ’75 to ’76 and ’76 to ’77; it just didn’t rain enough. Figures supplied by the MMWD’s Dana Roxon dramatically tell the story: “The winter of ’74-’75 we had 51 inches of rainfall, which is about average. But in ’75-’76, it dropped to 22.1 inches, and the next winter we had only 25 inches. They weren’t the driest years in Marin’s history,” adds Roxon. “It’s just that they occurred back to back.”

Unless the soil is saturated—which according to meteorologists takes at least five inches of rain—runoff into reservoirs simply doesn’t occur. “So for those two years,” Stroeh recalls, “believe me, I was dancing as fast as I could. Twelve- and 15-hour [work]days were the norm.” At the time he was barely 40 years old, married, father of three.

So what did he do as Marin was going dry? When previous months brought only a mediocre rainfall and it hadn’t rained by New Year’s Day 1976, he got antsy. By spring of that year, when Marin’s reservoirs were no longer full (even though February and March are often Marin’s wettest months), it was time to act. “Our first move was to encourage water conservation,” he recalls, by urging residents to use low-volume showerheads and put plastic jugs in toilet tanks to displace water and hence cut flushing volume. “We anticipated that would save 300 million gallons of water in the coming year.”

Those measures helped, but not enough. By June of 1976, it still hadn’t rained. Everyone in Marin was enjoying the balmy weather—except the increasingly concerned MMWD staff. While raising water utility fees would further reduce use, it would also bring down revenues—a classic catch-22—so the MMWD board came up with a clever scheme: Home and business owners using more than their previous year’s monthly averages would pay a premium on their overages of as much as 125 percent. The plan was a modest success, usage dropped slightly and revenues remained constant.

As summer became fall in 1976, there came a few sprinkles—but no gully-washers. And the natives were growing restless as lawns and parks turned browner and dustier by the day. “I think it’s psychologically damaging to ask some consumers to curtail their water use, when others are building swimming pools,” one MMWD director reportedly proclaimed. “Any more statements like that and we’ll be bankrupt,” a prominent pool contractor replied.

By December of 1976, and still no deluge, Marin’s reservoirs were at half capacity. And since desperate times call for desperate measures, as the old saw goes, Congressman John Burton made a suggestion: Station the Sixth Fleet in San Pablo Bay and use the Navy’s desalinization capabilities to meet Marin’s water needs. Others thought of using tanker ships to import water, but Stroeh pointed out that would be too expensive. Weeks later, however, he did propose having an iceberg towed up from southern Chile, according to The Man Who Made It Rain (Public Ink, 2006), a book by Michael McCarthy that chronicles the entire episode. “I told the board we’d anchor it in Tomales Bay, then have bulldozers break it up and earthmovers take away the big pieces for melting and storing in huge tanks.” The idea wound up as mere fun fodder for the national press now covering Marin’s plight.

By December of 1976, and still no deluge, Marin’s reservoirs were at half capacity. And since desperate times call for desperate measures, as the old saw goes, Congressman John Burton made a suggestion: Station the Sixth Fleet in San Pablo Bay and use the Navy’s desalinization capabilities to meet Marin’s water needs. Others thought of using tanker ships to import water, but Stroeh pointed out that would be too expensive. Weeks later, however, he did propose having an iceberg towed up from southern Chile, according to The Man Who Made It Rain (Public Ink, 2006), a book by Michael McCarthy that chronicles the entire episode. “I told the board we’d anchor it in Tomales Bay, then have bulldozers break it up and earthmovers take away the big pieces for melting and storing in huge tanks.” The idea wound up as mere fun fodder for the national press now covering Marin’s plight.

Early in 1977, and still no rain, legendary Chronicle columnist Herb Caen lampooned Marin residents as “visiting long-lost East Bay relatives just to enjoy a hot shower.” Slogans like “Save water—shower with a buddy” and “If it’s yellow, let it mellow; if it’s brown, flush it down” gained currency. Neighbors reported on neighbors for wasteful water habits; others, under cover of darkness, hooked up hoses and stole water off the meter next door. On the positive side, McCarthy’s book recounts, many Marinites learned to read their water meter, monitored their consumption closely, placed buckets in their showers to recapture water, and held block parties where prizes went to the most water-frugal families.

By spring of ’77, something had to be done; summer was coming, and all of the Bay Area, as well as the state, was feeling the pinch of meager rainfall. But nowhere near like Marin—where fish were dying in Nicasio Reservoir and restaurants served water only on request. (At the Valhalla in Sausalito, legendary owner Sally Stanford put a “Closed for Repairs” sign on the men’s room door. “I cut my water bill in half,” she later remarked, “and for months, men peed in the bay.”)

“We held Bay Area district meetings,” recalls Stroeh, “and with help from Supervisor Gary Giacomini and Congressman Burton, I managed to get 250,000 acre-feet of water from Los Angeles’s Northern California allotment.”

But getting the water from the Sacramento River Delta to Marin was a huge problem. “We had no pipelines,” recalls Stroeh. He cajoled the Contra Costa Municipal Utilities District to have pipes made available that would bring fresh water to Richmond. Now the challenge was to get it across the Richmond Bridge, a six-month engineering job estimated to cost at least $6 million. “We didn’t have that kind of time,” recalls Stroeh. “Or anywhere near that kind of money.”

After attempts at seeding clouds, dousing for new aquifers, and a West Marin Indian rain dance that was followed by a brief shower, Stroeh returned to the conference table. “Arnold Baptiste, a former Marin County supervisor, was a onetime friend of then-President Jimmy Carter,” he recounts. “So Giacomini and I flew off to Washington and met with Carter’s people and Burton’s staff in an effort to get money for Marin, which everyone constantly referred to as ‘one of the richest counties in the country.’” MMWD’s man-in-the-hot-seat wasn’t optimistic.

Yet somehow, by playing politics and stressing that not only Marin but also the consistently Democratic entire Bay Area was close to having no water, they made their case, and financial aid in the millions was promised. “I was assured the proverbial check was in the mail,’” Stroeh says. “But after Caltrans gave the go-ahead to use the Richmond Bridge’s right lane and six miles of 24-inch pipe were in place, the money still hadn’t arrived.”

The happy ending could not have been accompanied by a greater instance of bureaucratic bumbling regarding, of all things, the check’s payee. “Finally, in June of 1977, with the pipes in place and water flowing over the bridge into a parched Marin County,” Stroeh recollects, “I was presented with the federal government’s check for an initial payment of three million bucks at a ceremony near the Richmond Bridge.” And after the hoopla calmed down, the exhausted general manager took a sentimental moment to glance at the check. “I couldn’t believe my eyes,” he says. “It was made out to me personally.”

That winter’s rainfall figure was one of the highest on record.