“Living in Muir Beach,” says Debra Allen, a realtor who’s lived in this tiny, scenic, serene coastal community for 22 years, “is like living in the middle of nowhere” After saying that, Allen proudly declares her secluded community is just a 15-minute drive from her Pacific Union office in downtown Mill Valley.

And it’s undoubtedly a far cry from how it was back in 1898, when Portuguese immigrant Constantino Bello operated his Golden Gate Dairy here on the three ranches he bought on surrounding lands. Twenty years later brother Antonio Bello built a beachside hotel that stood 10 years before burning down; in fact, until 1940 the area was called Bello Beach. Most say the name “Muir” was picked not to honor naturalist John Muir but to capitalize on Muir Woods, the nearby national attraction that even then was drawing tens of thousands of tourists each year.

A bar-restaurant-snack stand complex known simply as the Tavern, built in the mid-1930s, was Muir Beach’s main amenity until 1967, when the state acquired the beach and a parking lot was needed. During World War II a navy artillery spotting station called the Overlook, on a promontory just to the north, protected San Francisco Bay from enemy warships (the concrete bunkers are still standing). In 1958 the Muir Beach Community Services District (MBCSD) was formed. Half a century later, it occupies an office and clubhouse on Seacape Drive that’s pretty much the heart and soul of the Muir Beach community today. “We don’t know exactly how many people live in Muir Beach,” MBCSD district manager Maury Ostroff says. “We do know there are about 150 homes.”

Directions to Muir Beach are easy: Take the Highway 1 exit from 101 and, after six mostly twisting miles, you’re there. Surrounding landmarks include the Green Gulch Farm Zen Center, the educational farm Slide Ranch, and, two miles due north, Muir Woods National Monument, which now attracts over a million visitors annually.

Directions to Muir Beach are easy: Take the Highway 1 exit from 101 and, after six mostly twisting miles, you’re there. Surrounding landmarks include the Green Gulch Farm Zen Center, the educational farm Slide Ranch, and, two miles due north, Muir Woods National Monument, which now attracts over a million visitors annually.

As communities go, Muir Beach is a hybrid. “We have Sausalito’s zip code (94965),” says realtor Allen, “and our kids go to Mill Valley’s schools.” PG&E provides electricity, SBC the phone service; the CHP and the Marin sheriff’s department frequently patrol; MBCSD provides water; sanitation is by septic tank. Cell phone service is spotty, cable nonexistent.

As for fire protection, meet John Sward, chief of the Muir Beach Volunteer Fire Department since 1970. “I moved to Muir Beach in 1967, when I was 24, during San Francisco’s Summer of Love,” says Sward with a confident smile, “and my wife Kathy and I have lived pretty much in the same house ever since. I’m a community-minded guy who loves fog; Muir Beach has been perfect for us.”

Apparently, the Swards have returned the favor. Next winter on December 11 and 12, Kathy will help stage the Quilters of Muir Beach Annual Holiday Craft Fair at the community center. And recently on Sunday, May 25, John Sward, now 65, presided over the 14-member department Muir Beach Volunteer Fire Department’s 36th Annual Community Picnic. “Back in the ’70s, when we started, we had a hundred or so turn out,” he recalls. “Now, every year, we’re serving barbecue chicken and homemade desserts for between two and three thousand—and it’s all been by word of mouth. We’ve never advertised. People come from everywhere.” As for actual blazes to put out, “we’ve gone a long time without any serious fires,” Sward, knocking on a nearby wooden railing, allows.

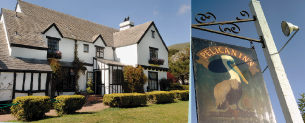

Possibly Muir Beach’s greatest crisis ever was the development controversy over the Pelican Inn, a Tudor-style authentic English pub and hotel at the corner of Shoreline Highway (Highway 1) and Pacific Way—today Muir Beach’s only commercial enterprise. Opened in 1979, it was the fantasy of Englishman Charles Felix, an advertising executive who endured eight years of community opposition before he could build.

Possibly Muir Beach’s greatest crisis ever was the development controversy over the Pelican Inn, a Tudor-style authentic English pub and hotel at the corner of Shoreline Highway (Highway 1) and Pacific Way—today Muir Beach’s only commercial enterprise. Opened in 1979, it was the fantasy of Englishman Charles Felix, an advertising executive who endured eight years of community opposition before he could build.

Nowadays, during electrical outages in winter storms, Muir Beach residents often seek refuge in front of the inn’s massive brick fireplace or in its heavily beamed dining room, patio eating area, or tiny bar dominated by the requisite dartboard; the inn has seven cozy rooms upstairs for overnight guests. “Pelican was the original name of Sir Francis Drake’s 70-foot galleon that sailed from Plymouth in 1577 and reached nearby Point Reyes in 1579,” inn manager William Koza recounts. “Drake’s 18-gun vessel was later renamed the Golden Hinde.”

If more than an overnight stay in Muir Beach is of interest, you might face a long wait, realtor Debra Allen says. “During a busy year no more than three or four homes change hands. Some people wait years before finding a Muir Beach home that meets their needs.” And many properties are sold “off market”—privately among relatives or friends.

Acquiring anything with an ocean view for “around a million” means you should “be prepared to do a lot of work,” she adds. Nonview lots sell in the $600,000 to $900,000 range. Allen’s highest-priced recent Muir Beach sale was $1.9 million for a “beautiful, lower-level property with ocean and hillside views.” A half-acre parcel with two small cottages recently went for $1.4 million. At press time a newer three-bedroom plus guest cottage home was available through Marty Bautista of Frank Howard Allen’s Greenbrae office for $1,349,000.

Currently, three homes are under construction in Muir Beach, a sight Allen doesn’t recall witnessing in all her years in this unconventional enclave. “Muir Beach isn’t for everyone,” she says. “But those of us lucky enough to live here really love it. It feels like we’re in ‘the middle of nowhere,’ but we really aren’t.”