Salmon are one of the most remarkable and resilient fish on the planet — living between ocean and land. After three years of fattening up in their Northeast Pacific feeding grounds, the Central Valley’s spring-run Chinook (or King salmon) are returning to their natal spawning grounds in the Sacramento and San Joaquin River systems. Unfortunately, this year’s salmon count shows signs of collapse. Like most iconic populations south of Alaska, Pacific salmon are facing an extinction crisis. It raises the question of how we can better support our greater wild salmon watersheds. The answer may lie in Marin’s success in scaling salmon habitat restoration and regenerative agriculture. You also may want to think twice about ordering farmed Atlantic salmon.

Experiencing the Remarkable Wild Salmon Lifecycle

Salmon are a cold-water keystone species, native to the cool, clear rivers of temperate rainforests in the Northern Hemisphere. While only one species of salmon exists in the Atlantic Ocean, there are seven species found along the Pacific Rim — five of which thrive on the North American West Coast, including Chinook (King), Coho (Silver), Chum (Dog), Sockeye (Red) and Pink (Humpback). The endangered Central Coast Coho are the dominant species found in Marin creeks. Whereas larger rivers like the Sacramento River primarily support the largest of the salmon species, Chinook. There’s also a land-locked sub-species of bright red Sockeye that can be found in the alpine rivers of Tahoe.

Salmon are anadromous fish, meaning they are born in a river and then journey thousands of miles to the productive northern ocean for one to three years to feast on herring, squid, crustaceans and krill. Once they reach maturity, salmon smell their way back to their natal river or stream, using Earth’s magnetic fields to navigate, where their bodies transform (e.g., males develop hooked snouts) in preparation for their mating ritual. Once they arrive at their place of birth, the mature female selects a male to fertilize her nest of eggs, called a redd. They perish shortly after.

My salmon journey began in my younger days serving as a naturalist in Alaska, where salmon returned in the millions each summer. Venturing up the Kenai River from Homer, we’d witness athletic salmon leaping up cascades, getting swiped by grizzlies, and dragged into the forests by bald eagles and wolves. The salmon carcasses saturated the forests and riparian zones with marine nutrients, feeding the entire ecosystem, including their offspring. Usually, Steelhead, also called Rainbow trout — a salmonid cousin that can swim back and forth from the ocean — will lurk around feeding on salmon eggs. This prolific lifecycle is what makes salmon a “keystone species” in the Pacific Northwest. They are also a way of life for indigenous peoples, like the Yurok and Winnemem Wintu tribes in Northern California, who to this day tell stories of crossing rivers on the backs of salmon, regarded as their ancestors.

In Marin, there’s no need to go to Alaska to observe the salmon lifecycle. They return each January from the ocean to Redwood Creek, Lagunitas Creek and Walker Creek, enriching our redwood forests. Just last year, the San Geronimo Golf Course was restored to its native habitat, providing gorgeous walking trails along Lagunitas Creek’s spawning grounds that are easily viewed from Geronimo Commons and Roy’s Riffles. Directly west is Leo T. Cronin Fish Viewing Area and Inkwells, where salmon leap up small cascades near Shafter Bridge, and over at Camp Taylor in Samuel P. Taylor State Park Turtle Island Restoration Network (TIRN) offers guided tours of salmon spawning sites on weekends from January 7 to 28 for $15.

Eric Ettlinger, an aquatic ecologist for Marin Water, summarized Marin’s 2023 salmon count. “We saw both positive and negative signs for Marin’s salmon population,” he advised. “Roughly 200 fish re- turned from the ocean to Lagunitas Creek this year. That’s well below average, but a generational improvement from three years ago. The exceptionally wet winter likely washed away many of the eggs that salmon laid in Lagunitas Creek, but — on a positive note — the surviving juveniles will have plenty of water all summer.”

No Water, No Fish.

Fishing salmon has been part of the Bay Area’s heritage and nourishment for centuries. Our Chinook salmon season kicks off in May when the summer fog flows over the Marin Headlands and through the arches of the Golden Gate Bridge. Typically, the docks of Sausalito and San Francisco bustle with excited sport fishers telling tales of wrestling 35-lb Chinook from their lures. Fish markets, and restaurants such as Scoma’s, Fish Restaurant and Mill Valley’s newly opened Coho, look forward to featuring the delicious local salmon catch on their menus. These businesses and their customers take pride in sourcing from wholesale fish suppliers like TwoXSea that support local, small-scale artisan fishers.

This year, however, local line-caught salmon is off the menu. The Central Valley spring-run Chinook (a threatened population) had another record low salmon count while the fall-run Chinook pre-count totals 170,000 fish. Historically, the run has numbered in the millions, and is down to a trickle of fish with low genetic diversity. After three years of drought and low fall-run returns, the fishing regulators — California Department of Fisheries & Wildlife and the National Marine Fisheries Service — are declaring a two-year closure for the commercial and sport salmon fishing season. This marks the second closure in California’s history since the 2008 season.

An estimated $1 billion in revenue will be lost in California as a result. “We’ve been through this before. It’s a complex situation that’s especially hard on commercial fishers who depend on the profitable salmon for their livelihood,” says fisherman and fellow conservationist, Dick Ogg from Bodega Bay.

“It’s not a banner season for the Salty Lady,” admits Sausalito sport fisherman, Captain Jared Davis. “The closures go beyond salmon. This is about equity in water allocation, which is mismanaged in California. I’m not a politics guy, but salmon and the environment deserve a seat at the senior water rights table. Salmon have been here for millions of years.”

Before the Gold Rush, the Central Valley teemed with wetlands and floodplains soaking up the Sierra runoff, rich with biodiversity, wintering birds and fish. Now it is one of America’s richest farmlands, accounting for 25 percent of the nation’s food supply and adding $17 billion a year to the economy. The problem is that agriculture in the Central Valley uses 80 percent of California’s precious water resource, and very little is left for salmon to spawn.

“No one is saying stop farmers. I support mom-and-pop farms,” Davis adds. “It’s the multi-billion dollar corporate farms that maximize profits by exporting thirsty almonds and pistachios to China and India using California’s water subsidies and unreformed water policies from the mining era.”

“The closure of the salmon fishing season is tragic both for the fish and the people who depend on them,” says Ettlinger. “There are no easy solutions. Ultimately it comes down to how much water and land we’re willing to share with the fish.”

Making Dam Sense for Salmon

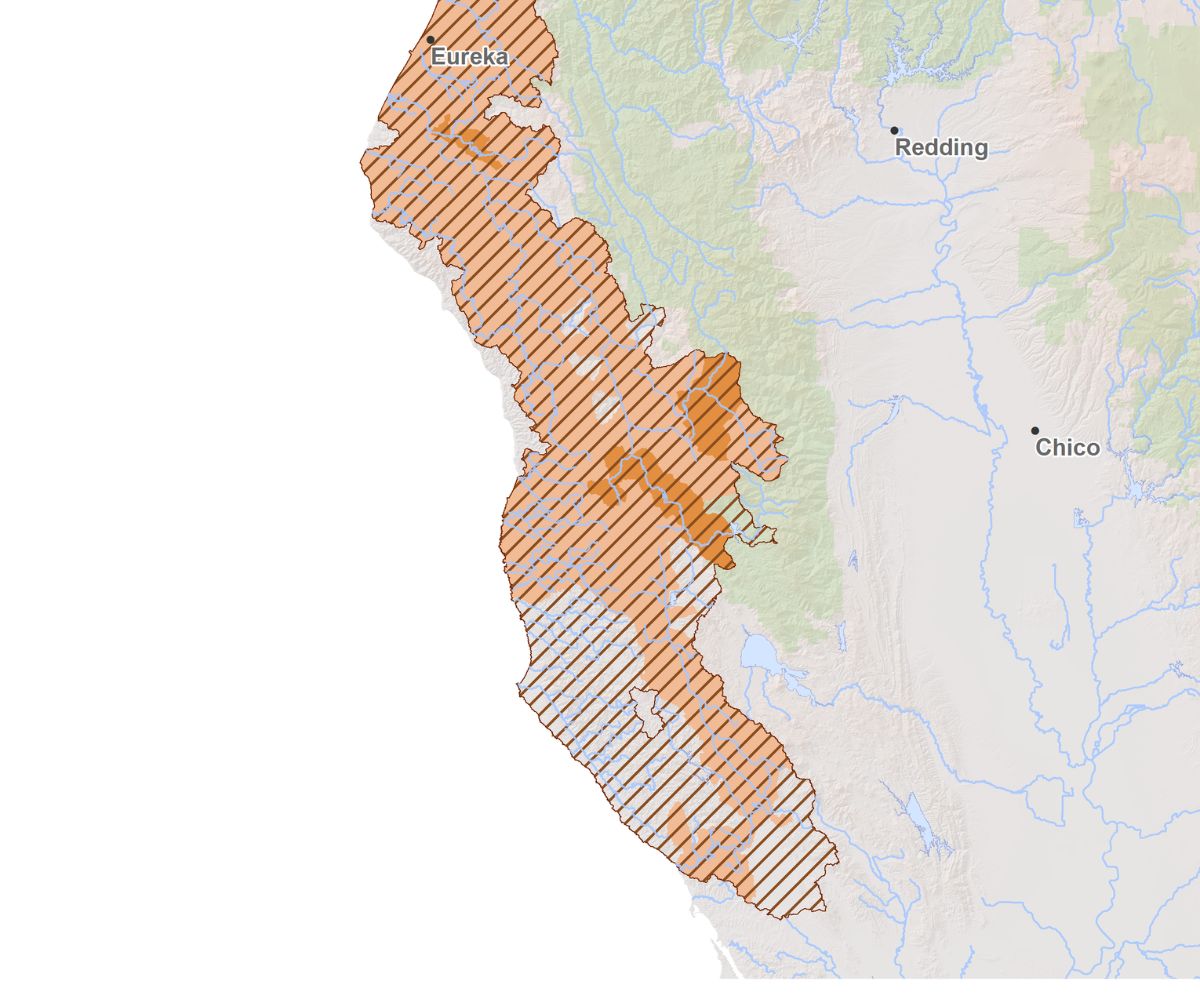

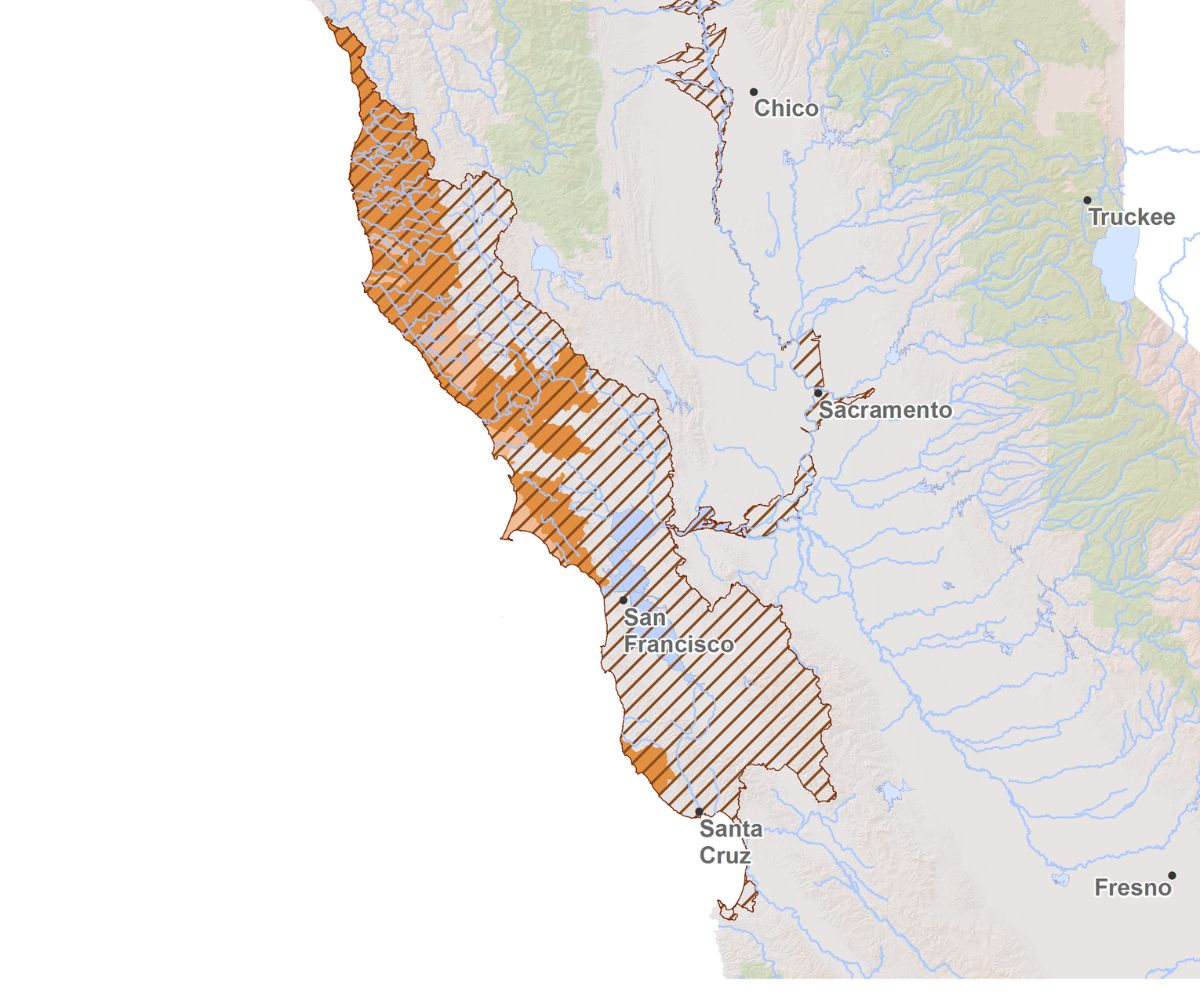

Since self-supporting salmon are under a lot of stress in our greater salmon ecosystems, it’s important we conserve our water use and release enough dam water in California. To survive the dams in the lower Sacramento and San Joaquin River basins, most Chinook depend on government intervention, including a system of hatcheries, truck shipping, and water-cooling towers. Like Marin Coho, historically, Central Valley Chinook bred in cool, clear pools in higher-elevation tributary streams, most of which have been cut off 50 percent by dams for agricultural use. (See historic spawning map).

With the added stress of climate change, endangered salmon are also more at risk of perishing in lethally warm water lacking enough oxygen. In February, alarm bells were raised for conservationists when Governor Newsom waived state rules requiring the release of Central Valley reservoirs to protect wild salmon. In addition, warming ocean currents impacts the prey of salmon. Scientists recently discovered Bay Area salmon are suffering from a thiamine deficiency, due to a mysterious climate-driven anchovy boom off California’s coast. The wild salmon diet switched from herring and crustaceans to anchovies, which produce an enzyme called thiaminase that breaks down thiamine in salmon, causing lethargy and mortality.

Salmon are incredibly resilient. After all, they survived over-sedimentation and river destruction caused by mercury-laced hydraulic gold mining and clear-cutting of forests. Salmon have also endured ice ages and warm epochs for millions of years. However, removing problematic dams is now critical for salmon survival.

“Our local salmon in Marin are at the southern end of their global distribution,” Eric Ettlinger explains. “Climate change will likely shift their range northward.” Due to growing drought conditions, Marin’s dams for municipal water are here to stay, as is Shasta Dam.

In regions north of the Bay Area and across the globe, there is a renaissance of removing dams lacking enough benefits. Restoring Washington’s free-flowing Elwha River in 2014 provided immediate results for salmonid abundance. Last year, Governor Newsom moved forward on approving the world’s largest dam removal project — the four Klamath dams at the California-Oregon border — a great success story for the Yurok tribe and for the salmon. The Winnemem Wintu tribe is similarly hoping California will approve a salmon “swim-way” around Shasta Dam. They are currently piloting a project to truck winter-run Central Valley salmon back and forth to their ancestral spawning grounds in McCloud River. This mitigation effort for impassable dams is commonly practiced in Washington’s over-dammed Columbia-Snake River Basin. Even though trucking salmon around dams is not a long-term solution, the McCloud River finally has salmon reproducing in its waters after 75 years of separation.

Another optimistic possibility is the momentum to remove America’s most controversial dams. The lower four Snake River hydroelectric dams in Washington — which separate salmon from their historic spawning grounds in Idaho — have been the source of protest for decades. The removal of the lower Snake River dams would help resolve treaty promises made to Northwest tribes and benefit the endangered Southern Resident orcas, which evolved to exclusively hunt Chinook. The habitat of Southern Residents extends as far south as San Francisco, where Chinook was historically abundant like Washington’s coast and the Salish Sea. Many wheat farmers in Eastern Washington are on board to support endangered salmon and orcas by transporting their grain on trains instead of river barges. However, replacing the barge-port economy and carbon-free energy benefits of Washington’s hydroelectric dams must pass Congress. Preventing the extinction of Idaho salmon and Southern Residents requires nonpartisanship — which is a challenging task in America.

The Great Irony of Farmed Salmon

Salmon fishery closures are not unique to drought-prone California. The global decline of wild salmon is systemic and interconnected. As a researcher specializing in ocean sustainability, I began investigating solutions to the global salmon decline several years ago, after experiencing the repercussions of a messy salmon closure in British Columbia (B.C.).

The wild salmon decline in B.C. was exacerbated by farming Atlantic salmon in hundreds of open-net pens, owned by Norwegian companies. Canada’s Department of Fisheries and Ocean (DFO) permitted the farms in the 1970s to be located directly on the Pacific salmon migration path. When I arrived at the Northern Gulf Islands in the Inside Passage to make acquaintances with Southern and Northern Resident orcas in 2019, I was shocked by what was happening around me. Grizzly bears were going into hibernation emaciated and First Nations were protesting (at times “occupying”) the salmon farms in their traditional territories. The great irony of farming salmon in open-net pens is that farms spread diseases, lice, pollution, and bad genes to the native salmon ecosystem. Salmon farms are also known to pollute coastlines with excrement and fishing gear.

Norway spread the farmed salmon industry to temperate coastlines around the globe once their own wild Atlantic salmon fishery collapsed mid-century, due to overfishing. Now, farmed salmon is the fastest-growing food industry in the world. Although improvements have been made, in most cases, the fish food that feeds carnivorous salmon contains pesticides and promotes the overfishing of small fish like sardines in the Global South.

Thankfully, Atlantic salmon farms are banned on the West Coast of the United States, and Canada is slowly doing the same. But farmed salmon remains ubiquitous across markets and menus. For ocean-conscious pescatarians, make sure to ask the chef if the salmon is farmed in open-net pens. I discovered that many of my favorite restaurants were serving the controversial farmed salmon from British Columbia, further fueling consumer demand.

Scaling Salmon Habitat Restoration

Having worked for organizations such as the Golden Gate National Parks Conservancy, which restored Redwood Creek for endangered salmon at Muir Beach, I’ve learned a lot about the successes of salmon restoration and sustainable aquaculture. Here in Marin County our legacy of conservation significantly benefited wild salmon and trout survival. A local partnership, known as “SPAWN,” between Marin Water, National Oceanic & Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), and TIRN, restored Lagunitas Creek. For years, they cleared debris, renewed the historic floodplain with enhanced native plant riparian corridors, and installed large logs in the creek to create side channels for salmonid habitat and protection. Similarly, California Trout restored salmonids in the Walker Creek watershed adjacent to Tomales Bay by working with ranchers to keep more water in rivers for fish. These multi-benefit efforts also help flood protection, endangered California freshwater shrimp, and migratory birds. Most recently, the City of Mill Valley made plans to restore Old Mill Creek for salmon passage by recontouring the streambed and removing obsolete concrete blockages.

Like the Central Valley, “Walker Creek’s working watershed has a long history of cattle ranching, commercial farming, [and oyster aquaculture downstream in Tomales Bay at Hog Island Oyster Company,]” states Patrick Samuel, of CalTrout’s Bay Area program. “It represents the need to restore balance between fish, water and people.”

“Our goal is to double the number of wild salmon returning to California,” says Scott Artis, who recently left TIRN to become the new Executive Director at Golden Gate Salmon Association. “Marin is a microcosm of a bigger shift happening in California. The state’s water policies aren’t working, and we plan to form coalitions to mobilize positive change for this iconic species.”

Many conservationists call for water rights reform in the Central Valley, like they do hydropower reform in the Columbia Basin. The Nature Conservancy (TNC), California Trout, and their partners are backing win-win nonpartisan solutions for farmers and fish. TNC’s SalmonScape program and CalTrout’s Fish Food on Floodplain Farm Fields develop innovative ways ranchers and farmers can use their water rights to ensure that there is enough water in streams to benefit salmonids. Similarly, TNC’s BirdReturns program functions as a habitat timeshare for migratory birds that incentivizes farmers to keep their harvested fields submerged longer than usual in winter — which also benefits fish by creating much-needed fish food. Scaling these programs, along with water-saving, carbon-sequestering (no-till) regenerative farming practices helps create climate-bird-butterfly-fish-friendly farmland.

How to Sustainably Source Salmon

In recent years, I adopted a plant-based diet, limiting my seafood and salmon consumption to an occasional seasonally line-caught salmon by friends or family. The most sustainable choice is to not support industrial-scale fishing or eat fish. But if you’re buying salmon, choose sustainably-caught, wild Pacific salmon. I suggest sourcing from Fish and Whole Foods Markets in Marin, where high-quality fish are sustainability certified, and the price points are competitive. My favorite smoked wild salmon in the marketplace are made by Patagonia Provisions, headquartered in Sausalito and founded by renown wild salmon activist, Yvon Chouinard. Their salmon products are truly wild-caught, self-supporting salmon, meaning the fish were not artificially propagated in a hatchery (a form of aquaculture known as salmon “ranching.”) Even though hatchery salmon can be labeled as wild salmon and boosts fish supply to people, the overuse of hatchery aquaculture adversely impacts marine prey competition and the genetic resilience of truly wild salmon.

When it comes to farmed salmon, like all industrial food, there are good and bad choices, which can drive confusion and misinformation. Rules of thumb: If there is no sustainability label on the farmed salmon, it’s not worth consuming. If it’s flown halfway across the planet to your plate, it’s not a climate-friendly choice.

The farmed salmon industry is slowly moving away from controversial open-net pens to land-based farming in closed-system tanks to keep the ocean clean. Companies like Bluehouse continuously recirculate clean water allowing fish to swim in the current and limit pesticide use. If done right, microalgae and bacteria protein is the dominant fish feed ingredient, and the wastewater is recycled into organic fertilizer or reclaimed water. The water and energy intensity are generally very high, but accounted for in the sustainability ratings. If you are adverse to genetically-engineered food, be mindful that many salmonid farms favor GMO “franken-fish.” If you are seeking the best local option for a salmonid farm, I recommend sourcing from the family-owned Mt. Lassen Trout Farm or McFarland Springs Trout, which is sold at Fish in Sausalito.

—

All in all, there’s room for improvement in protecting our greater salmon watersheds. Even though endangered salmon are likely to continue struggling to survive in California’s warming climate, it’s critical we continue to restore more fish habitat and support our farmers in advancing water conservation and regenerative practices. When fish and farms coexist in harmony, it means we are doing our part to protect the environment for future generations.

Alison Loomis specializes in oceanic climate solutions and environmental storytelling.