Many Americans need a little help with transitions: a cup of coffee to wake up, a glass of wine to get social, some cannabis to wind down before sleeping. Often, it’s something a bit stronger: 16 million Americans rely on prescription stimulants to get productive in the morning, and 9 million turn to Ambien or other sleep aids to fall asleep. When it comes to meeting and recovering from a day’s whiplash-inducing demands on our energy, few of us do it without the help of some sort of substance.

Most are harmless in moderation. However, some scientists warn that over time, this habit leaves its mark. “If we learn that we require coffee in the morning or some kind of stimulant to wake up, and we learn that we require some kind of sedative from outside of us like alcohol or a pain pill or sleeping medicine to wind down at night, then it trains our minds to believe that we can’t access those states or make those transitions effectively on our own,” explains Dr. Dave Rabin, a psychiatrist and neuroscientist who studies resilience to chronic stress. “By teaching ourselves that, and by relying on something outside of us, then over time we actually lose the ability to access those states on our own.”

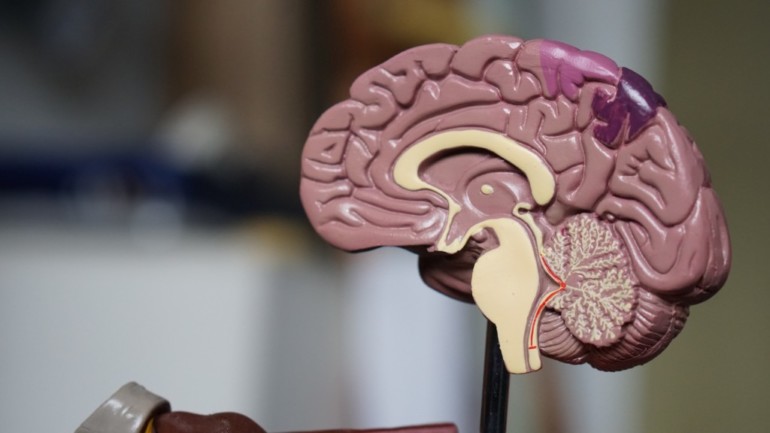

In other words, when we lean on these substances, our brains actually change. As with learning and forgetting foreign languages, the brain has been shown to operate based on a simple, harsh principle: “use it or lose it.” Nobel-prize winning neuroscientist Eric Kandel was the first to show the brain’s molecular changes associated with long term memory storage and learning.

Like speaking a second language, winding ourselves up or down is a skill that gets rusty when we don’t practice it.

We know that with languages, fortunately, the “lose it” part isn’t permanent. One widely cited 2009 study found that languages learned in childhood that feel just about forgotten can in fact be accessed again through practice; they’re not gone for good. The same is true for our ability to modulate our mood without assistance. Rabin continued: “This doesn’t mean we can’t access [these states] again with practice, it just means that the ability to access those states easily and reliably becomes a less effectively trained skill.”

But how do we re-train ourselves when we’ve been relying on these various chemicals every day for years? First, it’s worth considering: Why should we? If we rarely find ourselves without access to the substances we depend on, we may not feel particularly alarmed about the erosion of our neurological self-reliance.

One reason might be financial: Mood-modulation is a booming business, and many Americans allot hefty chunks of their budgets to the substances they need to energize and calm them.

For instance, 41% of millennials spend more money on coffee than retirement plans, according to Acorns’ recent Money Matters report. On average, Americans spend $1,100 on coffee each year, often for a lifetime — a number which doesn’t include other caffeinators like soda and tea.

Meanwhile, the country as a whole spent about $41 billion on various sleep aids and remedies in 2015, and that total was projected to grow to $52 billion by this year, according to BCC Research. Rates of insomnia are only rising, and the market for solutions is only getting bigger.

When it comes to prescription medications for mood and sleep, the financial risks of dependence are bound up with the country’s ongoing issues with health insurance. One recent study found that around 5.4 million Americans lost their health insurance due to pandemic layoffs this spring, and many risk becoming forced and unable to pay out of pocket for the medicines they’ve come to need.

On top of the financial toll is the risk that widespread dependencies gradually become more serious addictions. Ambien abuse, for instance, seems to be getting more common: in 2014, a report from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration showed an uptick in emergency-room visits due to zolpidem, the active ingredient in Ambien and many other sleep aids.

As marijuana’s legalization has come up for discussion in state after state, so have its health risks; while much remains unknown, data from the Mayo Clinic suggests that about 9% of weed-smokers get addicted — compared to 15% for alcohol and 32% for nicotine. Meanwhile, caffeine addiction is linked to insomnia, suggesting that it’s quite easy to become trapped in a cycle of mood-modulating habits that reinforce each other and are hard to break.

The bottom line is that while many of the substances we lean on are fairly harmless, our dependence on them does come at a cost. Rabin, for his part, has landed on a potential solution: a technique he stumbled upon in the lab and then developed for consumers along with his wife and CEO, Kathryn Fantauzzi. New in 2020, the product is called the Apollo, and it’s a clinically verified wearable band that uses sound vibrations to help us energize or calm down. Rabin compares it to tools like deep breathing, soothing touch and music, all of which he says help us modulate our moods without blunting our own ability to participate in the process.

“These things bring the central locus of control — and the ability to feel in control, which we call agency — back to the user,” he explains. “It’s really about reminding people that we all have the ability to access these different states of consciousness by ourselves without drugs. We’re born with that ability, but if we don’t learn how to access it then we often forget about it, and it becomes something that’s not strong.”

But even if we’re convinced it’s worth learning to modulate our moods with a bit more self-reliance, it’s no fun to do it cold turkey. On top of the whole experience of withdrawal, there are physiological reasons why things like meditation and deep breathing are the hardest to practice precisely when we’re most in need of their benefits.

“Top-down behavior change is actually much harder to do when you’re already stressed out,” Fantauzzi explains. “When someone cuts you off in traffic when you’ve had a bad day, you’re much more likely to overreact than if you just did a yoga session and came from the farmer’s market. Because you’re in a fight or flight state: you are sympathetically activated.” By targeting that sympathetic nervous system and gently deactivating it, the Apollo intends to provide some training wheels to help us break old habits and strengthen the mental muscles we’ve let weaken.

“Once you’re revved-up, or once you’re anxious, or once you’re angry, that tends to become a platform on which you build, and so spinning on a dime is not so easy,” explains cardiologist Bryan Donahue, MD. “It turns out that this device actually facilitates a little bit more grace in making that transition, say, from a sympathetic-dominant to a parasympathetic-dominant moment in the physiology.”

While the product of course has a price tag of its own, the company’s founding mission of giving individuals more agency over their own moods is part of a broader movement to resist trends of overprescription, addiction and general overreliance on the many companies, products and substances that do not always serve us.

Apollo won’t do it alone. But in the long run, both our budgets and bodies stand to gain from these kinds of efforts to tap into our natural resilience. As the demands of the workday become more intense, the challenges of winding up and back down again are only getting more difficult. If our culture’s dependence on substances does not rise along with them, it will be because we turn against the tide.

This article originally appeared on better.net.

How to help:

Consider supporting one of these local nonprofits that urgently need support during the pandemic.

More from Marin:

- Pedal Away From the Crowds to Enjoy Tahoe Safely

- A Better Buzz: Hard Kombucha

- Rebel With A Cause: Marin Conservationist Martin Griffin Turns 100

Eve Driver is a freelance writer based in Boston. A recent graduate of Harvard College, she writes on climate, technology, and travel and is also working on her first book.