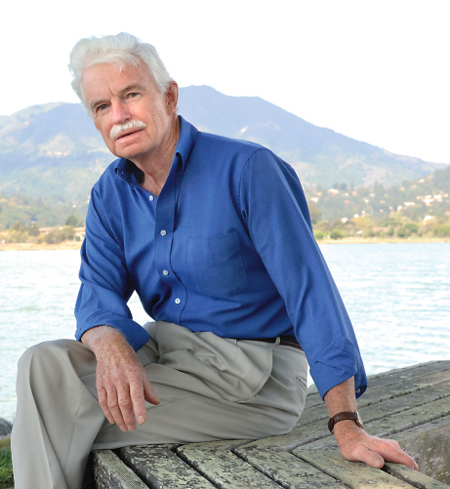

Although attorney Doug Ferguson says he has a short attention span, he’s a man of impressive consistencies — married to the same woman for 47 years, practiced law for 44, lived in Marin for more than 40, served the Trust for Public Land for 36, occupied the same Shelter Bay law office for 25.

“As my wife, Jane, has said, it’s a ‘superficial steadiness,’” Ferguson says, “and she both commends it and is concerned by it. I find myself doing 73 different things a day, and that keeps me fulfilled to the point where I don’t need changes in location, occupation, or volunteer pursuits.”

Scattered among the 73 different involvements that occupy Ferguson’s day are serving as a director of the Trust for Public Land, a national organization that acquires open space; acting as a pro bono legal adviser to EAH, a Marin-based nonprofit builder of affordable housing; and working with the volunteer entertainment troupe Bread and Roses; the West Marin nonprofit teaching farm Slide Ranch, and the Marin Theatre Company, Rafael Film Center, Larkspur Cafe Theatre and Save San Francisco Bay.

Oh, yes, Ferguson is also filmmaker George Lucas’s personal attorney and serves on the boards of most of Lucasfilm Ltd.’s wide-ranging business interests. He also writes music, plays the piano and sings (“badly,” he says).

At age 68, one can’t help wondering, might it not be time for Ferguson to retire, smell the roses and concentrate on hiking, skiing, sailing and canoeing? “I’m not afraid of retiring,” he says with a straight face. “Jane says she enjoys it and maybe I would, too.” But after a moment’s contemplation, he adds, “Maybe what I’m afraid of is giving up the life I so much enjoy. It’s a life so diverse and satisfying I often consider it a total scam.”

Then Ferguson cracks up laughing—at himself.

Over your 40 years in Marin, you’ve done so much for so many but never served in, or even run for, public office. Why’s that? Actually, in 1964, I did run for the Sausalito City Council. But being a busy young guy with three small boys in our family, I withdrew after the first month. Since then I’ve believed very strongly that while great things are being done by people in elective office, there is a role for people like me—and I’m not the only one—who’ll go out on their own and bring issues to the attention of elective bodies, badger them when they’re not doing their jobs, and generally serve as a militant activist.

I think this serves a huge purpose—and it saves me from staying up late for board meetings. That’s my style, although I’ve been asked to run several times since my aborted Sausalito effort.

What “militant activist” role has most consumed your time over the past, say, 40 years? I’ve now been on the board of directors of the Trust for Public Land for 36 years — which does on a national scale what many have done here in Marin regarding open space. It’s been enormously time-consuming but also very exciting when you consider what the board has accomplished. TPL differs from the Nature Conservancy, which deals with habitat protection relating to birds and bunnies, in that the Trust for Public Land deals with habitat protection for humans, who also need breathing space.

In addition, people can vote to buy open space; birds and bunnies can’t. TPL buys land where, as its slogan goes, “people live, work and play,” and that means parcels ranging from inner-city lands to the outermost stretches of the High Sierra.

TPL’s headquarters is in San Francisco, where we have a small executive committee that makes decisions fast, and we’ve brought about a lot of major transactions. Nationwide, TPL has an annual budget of $75 million and 350 employees in 37 branch offices, and we’ve acquired over 3,400 parcels of land totaling 2.2 million acres. Ten years ago we started the Conservation Campaign, enabling TPL to help communities identify desired parcels, devise bonding strategies and even name their campaign—which is very important—and then see that the issue passes and the land is acquired. We helped raise $5 billion in 1995, burned through that, got up to $10 billion by 2000, and now have raised over $24 billion. Over the past 36 years, I’ve donated a quarter of my working time to the Trust for Public Land. And as I say, it’s very exciting.

Returning to Marin, what do you consider the county’s crowning achievement—and your biggest concern for its future? I’m delighted by Marin’s efforts to obtain and maintain its most precious commodity—open space. Years ago, the absolute opposite appeared inevitable—freeways were headed toward West Marin, where thousands of homes and hotels were to be built. Yet those plans were turned away by a handful of people, all of whom were considered odd ducks standing in the way of progress.

It was all very time-consuming. However, as a result, a Countywide Plan was adopted and it’s been adhered to rather closely. And now, when I take visitors up into those hills and ridges and we look back at San Francisco, they ask in astonishment, “How can this be? We’re looking at an urban area while standing here, in the country—how could this happen?” That makes me proud.

Where I believe Marin is really failing is in meeting its need for workforce housing and all that entails for our teachers, firefighters and others. It’s a desperately difficult undertaking and elected leaders often throw up their hands in frustration. There have been successes—Point Reyes Station, Corte Madera and Tiburon—but I’m depressed to tears by what hasn’t been accomplished. Every project is met with an immediate upswelling of “not in my backyard” and that is sad, sad, sad.

Another concern is the shortsighted knee-jerk reaction, again and again, to any form of mass transit such as SMART. I’ve been here long enough to see environmental groups such as the Marin Conservation League oppose many good proposals. It’s very unsettling. How many more years of sitting in gridlock will have to happen before people realize that you can have mass transit with development nearby and still have ample open space? I really don’t know.

What do you consider your greatest personal accomplishments in Marin County? I’ve been lucky to have participated in a number of projects I’m really proud of—most of which I did with the help of several other folks. However, the one I did virtually by myself was the acquiring of Slide Ranch, the nature center near Muir Beach. In the mid-’60s, my father had died and I was ruminating about a fitting memorial and just happened upon Slide Ranch, so named because it was literally sliding toward China.

I tracked down the owner, a Hollywood scriptwriter, and began 30 months of negotiations that ended with the acquisition of the 150-acre property for $150,000, which at the time seemed like an astronomical sum. The seller’s vision was to build a hotel there and he initially thought it was worth 15 times that final price. After purchasing the property, my family conveyed it to the Nature Conservancy and it has continued to this day as [the site of] a wonderful program where people of all ages learn about nature, good nutrition and good animal care.

I’m also very proud of being part of the small group that derailed the development of Marincello, a planned town of 25,000 that in the late ’60s was about to be built in the Marin Headlands. It would have been a wedge preventing the massive Golden Gate National Recreational Area from ever becoming a reality. Now I take great delight in hiking those hills and thinking, “Let’s see, houses were going there; a hotel was planned for here; a shopping center there…”

Also, as an entertainment attorney, I am thrilled to have been part of a number of venues such as the Rafael Film Center in San Rafael and the Marin Theatre Company in Mill Valley. Lately, I’ve helped play a role in preserving the cabaret theater format of the Larkspur Cafe Theatre, purchasing the Lark Theater in Larkspur, and finding a new home for the Sweetwater in Mill Valley. All these efforts were very exciting.

How do you reconcile being a high-powered business attorney with that of advocating for open space and nonprofits? The concern for open space began when I was younger and fortunate to go to a very simple, Outward Bound–type High Sierra three-week scout camp —Spicers Lake, it was called. I was blown away by it.

It was an eye-opening experience. One day our scoutmaster asked us all, “You guys really like this place, right?” Everyone nodded, “Of course, of course.” Then he asked, “You know whose job it is to preserve it?” After a period of silence — bingo! I got it! Done! And I’ve never forgotten that.

The entertainment side comes from my father, a lawyer, who loved entertainment and probably wrote and directed more Bohemian Grove musicals than any other single person. He was a one-man show and that impressed me very much. As a youngster, I once told him I also wanted to be a one-man show and he said, “Well, just do it, just do it.”

I’m actually a business lawyer; it just happens many of my clients are entertainers, and when they come in [to see me] they usually have a few screws loose. I then say, “I think I know what you want to do and I think I know how to get you there.” I say, “I’m going to be your business guy and we’re going to make this show, or this movie, or this theater, happen.” It’s a great joy because I love the people I’m dealing with even though many of them are marching to a different drummer than most of us.

In your business career, have you encountered what you would call a true “creative genius”? Yes, twice I’ve encountered people who I believe were, or are, honest-to-goodness creative geniuses. One was George Lucas,the other Francis Ford Coppola. George is the one I worked closest with. When he came to my office, I didn’t know who he was — even though he’d just completed Star Wars — so I had to get a copy of Time magazine and read up on him; he was on the cover. Anyway, right away he impressed me as a good businessman, which most entertainers are not. He had an idea for a multitude of interrelated companies, which he envisioned achieving a lot of different things. I thought he’d been smoking some pretty powerful stuff and took notes as he read from his notes.

That was 35 years ago, and I wish I still had my notes because, almost unerringly, he has stuck with that initial plan. He is one of the best business people I’ve ever had the good fortune to work with—as well as one of the nicest guys you could ever meet. He’s fiercely loyal; we’ve been friends for many years.

Where do you think America, as a nation, is today? I am desperately unhappy with my nation. I love our country and its people—many of whom have tried as best they can to change the course of events we now see occurring. But I’m truly bewildered as to why people in national elections consistently vote against their own best interests. The Republican Party has persuaded people that they are the ones people should vote for if they’re socioeconomically lower class or blue collar—and that they will take care of these people which, of course, they don’t. My father once told me, “The average man is far below average,” and I’m now afraid he was right. If our falling from grace as a nation and the growing separation between the very wealthy and the many who are losing economic ground doesn’t make a difference, then what will? Have we all gone brain-dead? I’m beside myself. How will we ever wake up?

As for Iraq, I saw that coming. I wanted to go around grabbing lapels and shouting, “Do you know the history of the Middle East? And their delicate balance of power? Once we get in, we’ll never get out.” We as a nation, all of us, have been so brought up by political spin we’re now like Charlie Brown and the football game: “Well, maybe this time we’ll win.” Only our delusion is, Maybe this time they’ll be telling the truth. I’m for getting out of Iraq as soon as is responsible. But do I have a plan? I’m afraid I don’t.

Your father, a Bohemian Grove–attending attorney, sounds like a rock-ribbed Republican. You come across as a strong Democrat. What’s going on here? A very interesting gentleman once asked where I got my liberalism, because my father was indeed a staunch Republican, as all my family was. I told him I got it at a folk music concert I attended when I was 17 years old. That’s when I heard Pete Seeger sing about people and things I’d never heard of. Pete did an excellent job of converting me on the spot. And my liberalism has remained all these years… and served me well.