I started to look for him when his roman shades were up. An empty chair concerned me. Seeing him in it, reading his wife’s Kindle (as I would later find out), assured me that all was well.

How many times did I turn onto my street and ignore his house on the corner? For 17 years, going to and from my home with children in my minivan, I was too busy to pay much attention. Then, one day after my girls had grown up and moved away, the man in wireframe glasses and a beige bucket hat was tending his garden and waved at me as I drove by. I returned his wave and wondered, “What was his story?”

I knew my neighbors across and on both sides from us. I was good with two out of three. The one neighbor who made me feel unsafe quelled my desire to go beyond the borders of my property. Consequently, I considered everyone else a person of uninterest. “Don’t make eye contact” was my motto, especially when I was in the driveway, picking up newspapers in my bathrobe.

There was something about the man in the corner house, though, that made me curious. He was always smiling and waving at me. I wanted to knock on his door and say, “What the heck?” Honestly, I don’t remember how we officially met. Maybe I called out to him when we were getting our mail at the same time, saying something neutral like, “Hey, I like your plants.” I told him my name and he told me his, and the next thing I knew, I was dropping off a plate of Christmas cookies. This is a big deal. I only share my kitchen creations to those who will not judge me. It is the ultimate compliment of trust on both parties.

***

Brad Giles is his name. He has lived at his house in Greenbrae for 60 years. That is longer than I have been alive (by a few years). “I was never that itchy to move,” he says. Now that I know him better, it makes sense. That’s his MO — when Brad found something he loved, he stuck with it, whether it was a woman, a profession, or a home.

Like a good neighbor, I try not to bother him. Three years ago, when Brad told me he was 91, I was shocked. Sure, he had no hair, but he was gregarious, stood tall, had nice teeth, was all with it. I soon found out that he lived alone. His wife had died some years earlier. Brad says that on the scale of masculine to feminine, he is closer to the middle. He doesn’t mind doing the laundry, cooking or housekeeping. It is obvious that he takes care of himself. He takes daily walks and flosses, dresses in neatly ironed shirts, washes his car regularly, and gets the paint touched up on his house as needed. He doesn’t want to leave anything for his children to deal with when he dies.

Perhaps because Brad is so self-sufficient, I haven’t worried about him, assuming he will always be there, needing nothing from me. I realize, though, that our time is running out, because he isn’t as young as he used to be. The contagious coronavirus had me calling him, and then his daughter Dana in a panic when he didn’t answer his land-line phone. I decide there is no time like the present quarantine to fill in the gaps about his life. He sits in his favorite floral chair by the window, legs crossed, while I take notes on his white couch, six feet away. Dana, who is visiting from Southern California, bops in and out of the living room to add color to the conversation, and sometimes to boost her humble father’s memory. “You never take the glory,” she teases him. “What is this for?” he says, shyly, enjoying the company but unsure of my interest. It is not hard to be drawn into his stories. He is one of the Greatest Generation and his life reflects the definition of these hardy Americans. “Being such an average guy,” he says, “I’ve had a remarkable life.”

***

While Brad confesses that he never had his great-grandfather Daniel’s adventurous streak, he became a skilled outdoorsman as the original Giles settler must have been to make the perilous journey from the East Coast to the Wild West. Once in Oregon, Daniel first settled down with a woman named America. However, it was his second wife Indiana Henrietta who raised his brood of boys — and was the namesake of Brad’s beloved black lab a century later. Brad’s grandfather ran a brick factory (“a bucket and a bunch of mud”), but his sons had other ideas: three became dentists and one a lawyer. Brad’s father Clark was one of the sons that liked teeth. He left small town Myrtle Point for big city San Francisco with the determination to go to dental school. Clark must have been in a hurry. He was only 19 when he graduated, so he taught for two years until he could legally practice.

Born on November 23, 1926, Brad lived with both sets of grandparents, his parents and older sister Betty, in a two-bedroom, one-bath house that cost $4,000. Then the Depression hit. Clark was fortunate that his city practice was steadily growing enough to buy some breathing room in rural Lagunitas where the extended Giles family could play badminton and tether ball, and sleep in an 8-person tent when it was warm enough outside. Pre-Golden Gate Bridge days, Clark rode the train from Point Reyes to Sausalito, then took the ferry to the city. “I thought he was a wonderful father because it was such a long commute,” says Brad. After Clark became a charter member of the Meadow Club in Fairfax, he would sometimes drop off Brad and Betty at the pool on his way to work. “I had a heck of a childhood,” Brad says.

Of course, his mother Louise Catherine Pomtag deserves some credit for Brad’s genial and generous nature. Although she had a full house, she enjoyed inviting people over for parties. She liked to sing the line from Maurice Chevalier’s 1929 hit, “Every little breeze seems to whisper ‘Louise.’” He says she was a “roar” who never lacked for crazy ideas. One of the best: Since Louise had a double mastectomy after breast cancer, she once used her empty bra cups to hide her grandchildren’s illicit firecrackers during a border check. It worked.

For Brad’s father, the untamed land in West Marin brought him back to his Oregon roots and he instilled this knowledge in Brad. At age 8, Brad was shooting pine cones with his own shot gun. “I’m embarrassed to say I was raised to hunt and fish,” he says. Back in the day, I remind him, you hunted to eat. I see nothing wrong with learning to survive and being a good shot. “You did eat what you hunted,” I confirm. “Oh yes,” Brad says. “My dad would drop me off with a .22 rifle and tell me to get a deer in two hours. I was maybe 10-years-old and I would hide behind a rock.” Easier to capture were the exhausted salmon that had finished spawning in the creek. While others might complain about their task-master fathers, Brad saw him as “a good leader, not a follower.” Definitely a role model. “My father would point to a 30-foot fir tree and say, ‘I want that sawed and split, and put in the basement.’ And that is how I spent my summer. Talk about being a spoiled kid.”

The Giles’ languorous time ended while World War II raged. Supporting three families during the Depression and afterwards, Clark worked hard for his leisure and let it go when it was no longer justifiable. He sold the Lagunitas property after Brad joined the Navy. (If only he had known it’s worth today. Clark died with $10,000 in the bank.) Still, Brad’s passion for the outdoors was imprinted and he considered being a forest ranger for a moment. “He knows every bird flying by, every tree, every bush,” says Dana. “It’s incredible.” “No, it’s not incredible,” says Brad, humble as usual.

***

Make that Dr. Brad Giles. Another dentist. No wonder he has good teeth.

Brad was obviously smart. His parents insisted he apply to Lowell, the oldest public high school west of the Mississippi that continues to be an elite academic institution in San Francisco. “Do you know it?” he asks. (Admission there is akin to winning the lottery.) Brad got in and went to school with future icons like actress Carol Channing, GAP founder Don Fisher and Warren Simmons. He and Warren were yell leaders. Once, when it rained before a football game, Warren bought army surplus raincoats and sold them to the fans.

Brad says Warren had a knack for making money which he later used to develop Pier 39, create the Chevy’s restaurant chain and build a discount store that later morphed into Mt. Tam Racquet Club, the club I belong to in Larkspur. Life-long friends, Brad brings up Warren’s tennis achievements at Silverado Country Club in Napa. Brad says he wishes he learned to play tennis better. I note that is the only regret I have heard from him in our chats. In the company of affluence, Brad shrugs and says, “Money doesn’t mean a lot to me. I never felt I needed to be a millionaire, as long as I had enough to take care of my family, live well and be happy.”

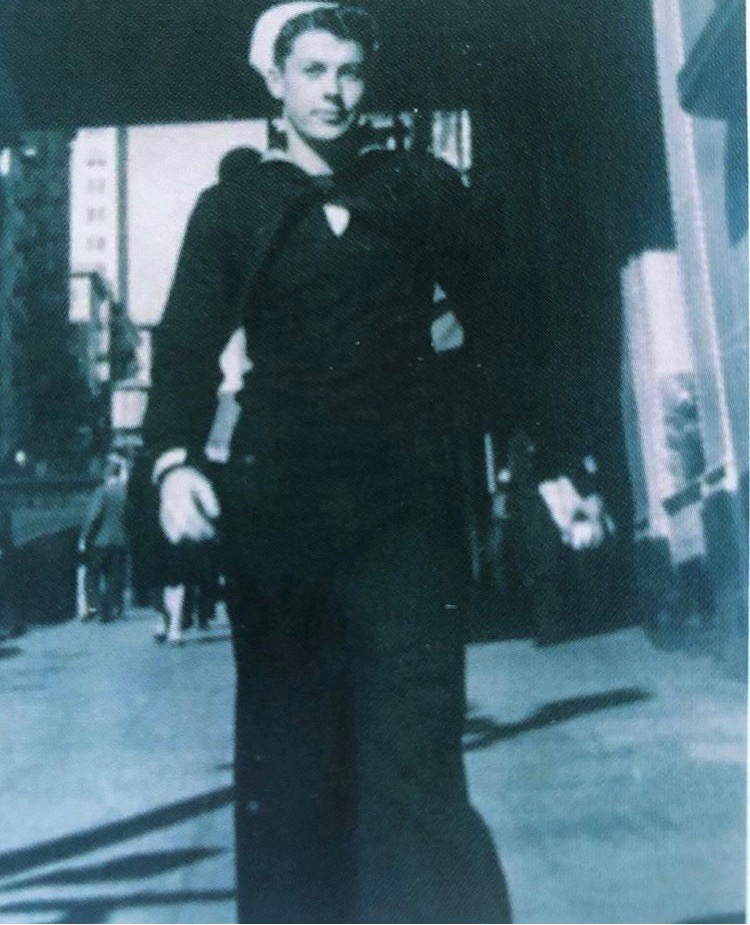

By the time Brad graduated from Lowell in February of 1944, World War II was in its fifth year and many of his older classmates had gone overseas to fight. Since he would turn 18 in November and could be drafted, he used the time to take a class at the University of California in Berkeley where a B grade assured him admission. With that accomplished, Brad committed himself to the war effort and voluntarily enlisted in the Navy so he could be assigned as a hospital corpsman. “I didn’t know any better to be afraid to go to war,” he says. He did know that he wanted to help the wounded, rather than do the wounding. How he became a dentist turned out to be circuitous and auspicious.

Stationed in Oakland, he started out as a surgical technician and scrubbed in on a hundred operations of injured veterans. “I don’t know if I had the brains to be a doctor, but I would get queasy,” he says. “I wanted a family life and there were more demands on a physician back then.” Choosing the more “selfish” route of being a dentist, Brad also trained as a dental technician. During his two years in the Navy, he went from San Diego to San Leandro to San Francisco where he worked on Union Square, and was paid $120 a month. Essentially, an angel decided that Brad should stay in California during the war and do all but six months of his dental training while getting paid. “Talk about a golden spoon,” he says. “I was so lucky.”

After graduating from Berkeley, Brad entered UCSF Dental School where his first-hand Navy experience landed him a clinical teaching job even before getting a degree, unintentionally following in his father’s footsteps. In 1952, Brad joined his father’s practice at the 450 Sutter building where many of the city’s doctors, dentists and labs were located at the time. Active in the San Francisco Dental Society, Dr. Clark Giles was well-respected and Brad learned from his example as his partner as he did as his child. His father had prioritized his family and so would Brad.

Clark also bartered for his dental services if his patients couldn’t pay. Beniamino Bufano, the artist and sculptor of numerous pieces in Northern California, became a good friend and prankster dinner guest: He pretended to bite off part of his finger that was already missing while eating lettuce. A painting of Bufano’s sister hangs in Brad’s living room, perhaps given to Clark for a root canal. Dana safeguards the portrait that Bufano painted of her father. “Why Brad?” I wonder. It speaks to the closeness of their family’s relationship to the artist, but also something special that he saw in Brad.

Brad never turned away a patient either, but maybe he should have thought twice when presented with a deal. “I had a patient who let me rent his house on Stinson Beach for $25 a month in exchange for dental services,” recalls Brad. “When he wanted to sell it to me for $16,000, I said, ‘Are you out of your mind?’” If only.

***

Brad knew Mary Ellen Duplisea since the seventh grade, but it took him a long time to ask her out. She was dating his best friend who was still away in the Navy and asked him to take her out as a favor. Brad loyally obliged and didn’t give her back. “I don’t think they were that serious,” so he says.

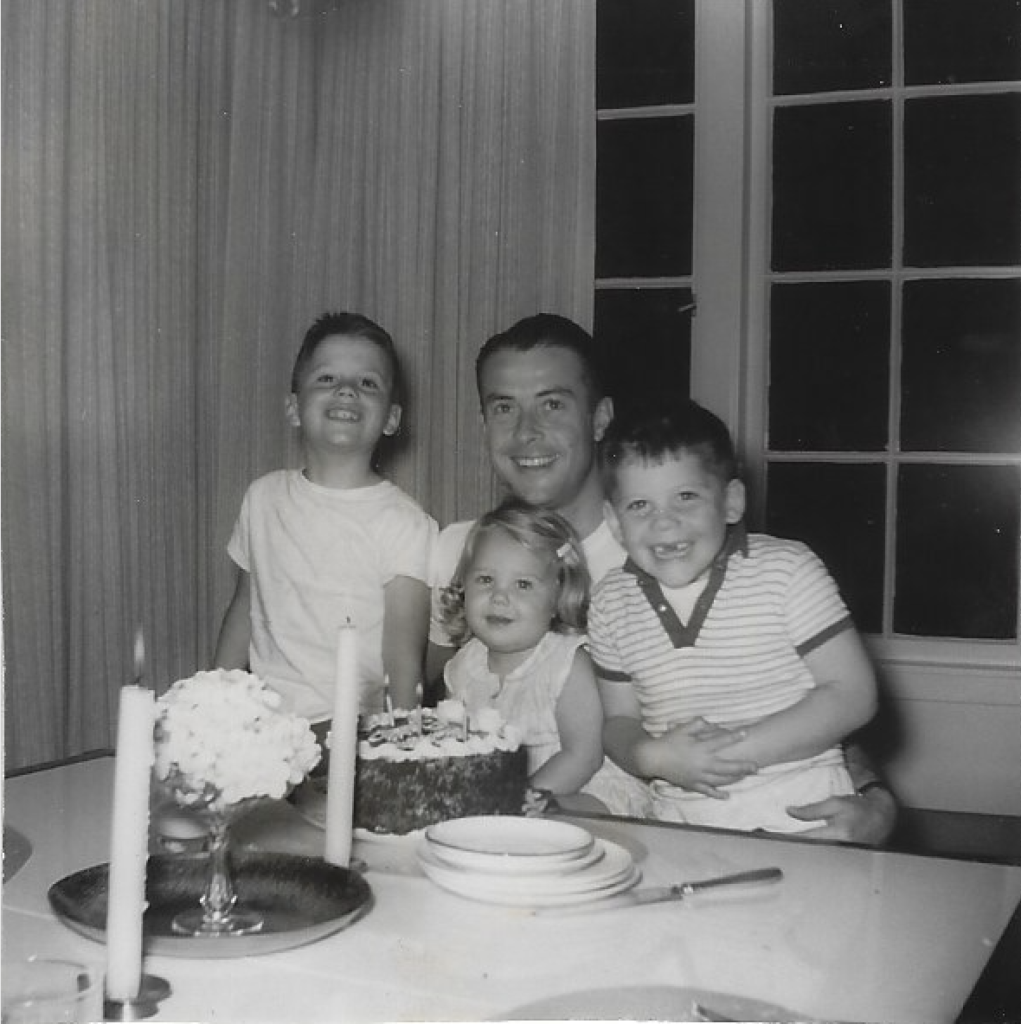

Ellen and Brad were married two years later in his second year of dental school. “I was just so much in love with her,” he says, and it shows in their wedding photo. He wears a dapper morning coat, looking like Clark Kent, broad-shouldered and beaming, clutching his bride’s hand. Her hair set in pin curls, Ellen is bright-eyed and elegant in a white satin gown. Vows said, they moved into a $25-a-month studio apartment in a building that Brad once painted on the weekends for extra money. It was fortuitous that the manager remembered his good work and gave him a discount.

“How did you end up in Marin?” I ask Brad. After a duck hunting trip at Grizzly Island, Brad and his father drove through a new development called Greenbrae. By this time, Brad and Ellen lived in San Francisco’s Forest Hills with their three young children. He relished his North Bay days and wanted to share them with his family. He went home to Ellen and said, “Let’s move to Marin.”

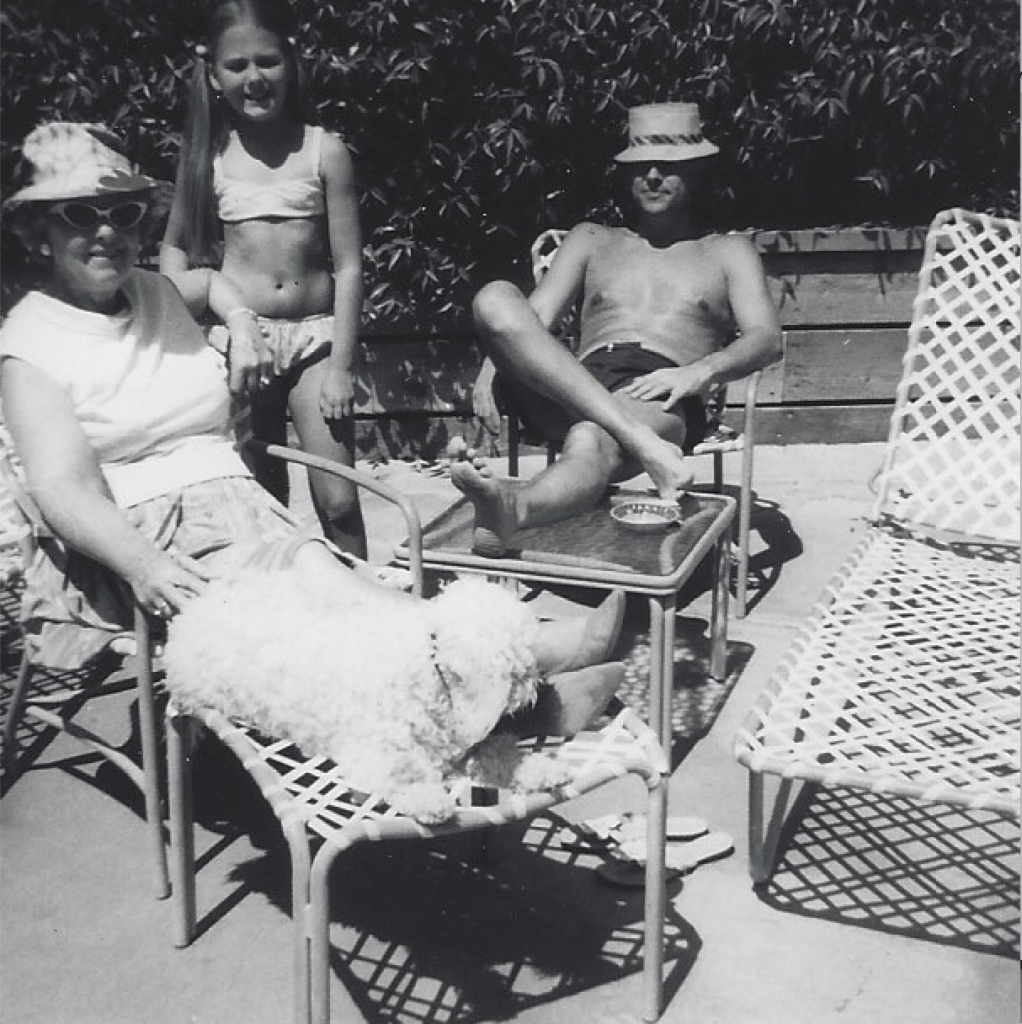

“I was always the instigator,” Brad says. “Anything I would suggest, she would agree with.” (Well, they did have one argument where she said, “If you don’t like it – Go.” “I was afraid to go,” he admits.) Although Ellen was a city gal, she met with the Greenbrae developer and chose a $9,700 lot with a spot-on view of Mt. Tam. In 1960, Brad and Ellen moved into their $27,500 home with their sons, Dixon and Kirk, and their toddler daughter Dana. When the pool was put in, the kids’ footprints were embedded in the cement.

The Greenbrae of his prime lived up to its name. Their house was surrounded by cow pastures until new neighbors bought up the lots around them. From his picture window, Brad recounts the notable families who owned this house or that. Children went to the now forgotten Greenbrae Elementary School. On Halloween, the hills did not deter the young tricksters in search of treats. The Bank of Marin’s Murray family welcomed the New Year with a canon blast at midnight. Fireworks were shot from the marsh behind Bon Air Center. Locals bought groceries at Petroni’s and scoops at Swensen’s Ice Cream. Weekends were busy bowling at Greenbrae Lanes and chowing down at Zim’s. For five dollars, the Mogul Ski Club bus took teenagers to Lake Tahoe to ski for the day and stop for dinner at the Food Circus on the way home. If the roads were clear, Dana was no doubt waiting on Sir Francis Drake Blvd for the 5 a.m. pick-up. It sounds like a bustling, more outgoing, more innocent time, and surely, it was.

***

Dana is a slim, vivacious woman with impeccable fashion sense. She resembles her mother whom Dana says looked like Dinah Shore or “Doris Day-ish”. I met Dana when she was walking her pixie dog on our street. She thanked me for befriending her father whom she adores, even though he never took her hunting with her brothers. She’s about my age with two daughters around the same ages as mine. So, we have that in common, too. I liked her immediately. When Dana comes to visit her dad, she cooks and freezes months of meals for him. “Dana can make anything taste good and look good, too,” Brad says. Of course, she had good role models in her parents.

Brad and Ellen were married for 64 years. Yet, I’m sure he would say it wasn’t for long enough. Brad says their secret was that they were good buddies and planned things together – and didn’t push each other to like something they didn’t. For example, Ellen didn’t like snakes. None-the-less, she agreed to an initiation camping trip that was interrupted by two rattlesnakes and a bear. She went back to reading her books by the pool. “I look at my wife and think, she tolerated a lot,” Brad says. “She was a saint.”

Actually, I think she played her cards right. He abated his guilt of outdoor excursions and professional obligations by reserving Wednesdays just for them. They ate lunch at the finest restaurants (cheaper than dinner fare) and attended plays and ballets. Their gourmet appetites spurred them to take cooking classes together, which they relished, whether it was from a $6 home chef or at Le Cordon Bleu for Brad’s birthday in Paris. Up to 30 family and friends would convene at their home for formal dinner parties and holidays where they honed their latest recipes, and their children served and cleaned up after. They were a team.

One of Brad’s favorite hobbies was buying Ellen gifts, which I consider a very good one. Then, he says, “I loved dressing her. I bought her clothes that I liked from Jim-Elle or I. Magnin.” This, I’m concerned about. Dana explains that Brad would see something in a store window and say, “That would look good on your mom. I’m going to come back when it’s open.” I find that sweet. “She was a classy lady,” he says. “She never returned anything.” Ellen must have seen the enjoyment Brad got when she wore the outfits he chose for her. Dana admits she borrowed her mom’s clothes from time to time. So, he did have good taste. The most coveted gift Brad gave to Ellen was the white convertible Mercedes 280 with the black roof. Ever thrifty, he got the diesel model because diesel cost 25 cents a gallon and gas cost 50 cents more. It was a good deal for both of them.

Like his father, Brad took his family on trips, but ventured farther afield. When the children were growing up, spring breaks at the White Sun Guest Ranch in Palm Desert, summers at Marla Bay in Lake Tahoe and respites at the Royal Hawaiian on Oahu were reserved every year. While their doting grandmothers made sure the kids were doing their homework, Ellen and Brad took their own adventures with bridge and travel friends Doris and Ray, who lived down the hill and were a complementary pair.

Before Ellen was stricken with crippling rheumatoid arthritis, Dana says that her parents were “show-stopping” dancers that would attract a crowd. “We would turn on the Lawrence Welk Show and they would dance in the kitchen.” At a niece’s wedding, Ellen was by then in a wheelchair, but it didn’t stop Brad from spinning her around on the dance floor when the music started.

“I made the living,” says Brad. “She made the living worthwhile.” For 64 years.

***

In the 1970s, Brad was called Marcus Welby in the dental community because along with teaching, he had the largest practice in San Francisco – more than 2,000 patients – and was generous with his referrals to specialists. (Marcus Welby, M.D. was a popular T.V. show in the 1970s whose eponymous lead was known for his kindness and dedication.) Not surprisingly, his colleagues looked to him for guidance and leadership.

Dana calls it the “Giles Syndrome” – he can’t get involved in something without taking it to the max. What Brad didn’t see in himself, others did and they encouraged him. “Pushed him” is how he would describe it. She lists some of his accomplishments: 30 years on the San Francisco Dental Society Board of Directors, President of the Parnassus Club, President of the University of California Dental Association. “I’m actually shy. I don’t feel confident getting up in front of people.” Brad shakes his head and says, “I would take responsibility and do a good job so everyone was after me.” Dana adds that her dad is probably most proud of being a president and coach of the Marin County Little League and running the Cub Scouts.

When Brad tells me about an insidious infection in his right ankle, likely caused by salmonella from drinking contaminated water from a stream, that plagued him for years, I am confused. How did he manage it with all of the above? He was diagnosed with osteomyelitis in 1957 and was initially told he may only have a few months to live. Obviously, Brad forged on and didn’t whine about it. Most people didn’t know he endured multiple surgeries and wore a leather boot with straps up his calf for stability. Eventually, he had to stop teaching and reduce his work schedule. Now, he can’t even remember when his ankle finally healed.

In 1991, Brad was given the Medal of Honor, the most prestigious award from the UCSF Dental Alumni Association. The following year, after 40 years of practicing dentistry at the age of 67, Brad was burned out and decided to stay home to care for Ellen as she was becoming more incapacitated. “I figured I was going to die at 70 anyway,” he says. He installed a stair lift in the house and made her his priority for 20 years.

Of all the things I have learned about Brad, the selfless, patient years taking care of his wife make him a hero to me. He says they had a schedule. She got her hair done every week. He dressed her as usual. His household skills came in handy. Day after day, with a smile on his face and love in his heart.

After a traumatic fall, Ellen died at the age of 87 on November 24, 2014, the day after Brad’s birthday. “She was always so appreciative of everything I did,” he says. “It was a pleasure for me.” He earned the Husband Medal of Honor.

Brad is still getting through the backlog of books on her Kindle. “I’ll never be able to finish them,” he says. Reading the same passages she once read, maybe he feels close to her that way. Hearing about the two of them, I regret never meeting her. By the time my family moved into the neighborhood, she was using a walker, rarely outside the house. What I didn’t see, I didn’t know. “She would have liked you,” Brad says to me. I know I would have liked her, too.

***

Brad has been a good neighbor to my husband Todd and me. When our driveway was a concrete mess, he let us park Todd’s car in his garage and gave us the opener for as long as we needed it. He always asks for news about my daughters and my mom, a youngster in her early 80’s. If I bring by some food my mom made, he returns the containers with lemon bars and recently, a can of tennis balls for me. Once, he came in and kissed my mom on the cheek. (And he says he’s shy.)

More than a year ago, Brad told me that he is dying. He was chipper about it. I was stunned. His lungs were hardening, slowing deteriorating. There was nothing that could be done about it. His acceptance of his illness was not surprising to me. Looking at him, though, I couldn’t imagine anything taking him down.

According to his doctor, he should be gone by now. Obviously, he isn’t.

I take off my shoes before entering Brad’s house. He, Dana and I sit in a triangle in his living room. I touch nothing, taking all coronavirus precautions since he is obviously in the high-risk category. Still, we are enjoying a reunion. At 94, Brad continues to take walks every day, though only a mile instead of two. He’s a little short of breath. His hips hurt a bit; his calves swell more. He still drives Dana to West Marin to reminisce. “I can’t believe it,” says Dana. “He just told me that his dad’s receptionist dated Lefty O’Doul. So, he got to sit behind all the great players at the Giants baseball games.”

“I’ve been so gosh darn lucky,” Brad says. “I’m not threatened by death.” He laughs. “I just want to go to sleep. The way the Lord has treated me, I’ll probably have a limo.”

“You’ll probably get picked up in a chariot,” says Dana.

Even after Brad told me about his illness, I didn’t visit him often enough, maybe once a month, less. The days just went by as I drove by his house to mine. I would look for him, though, the man in the window. I reprimand myself. Whenever I stop to knock on his door, I know I will stay longer than I planned and I will leave feeling uplifted, listened to, less anxious. Brad is living history with much to share. He is proof that a person can be happy on his own terms, by doing his best, teaching his students, treating his patients, providing for his family, caring for his wife. “You get what you give,” he likes to say. He gave a lot, and so, he believes he received much in return. I hope I can learn from that.

“I still feel so good,” he says. “I don’t feel like I’m going anywhere.” The funny thing is that he doesn’t seem that old to me. But I have to ask him those questions you ask someone who has lived almost a century. What are the secrets to a life well lived? “Be kind. Be honest,” he says. The secret to longevity? He doesn’t indulge in bad habits, gets fresh air, and eats a salad every day. Brad is a man of simple tenets and a sensible routine.

I ask if I can take a photo of him sitting in his chair by the window. He puts his hands in his lap and smiles. I know that one day, I will not see him there. I wish it didn’t take me so long to discover him, just two doors down. “See you later, kiddo,” he says, as I turn to wave. “I’ll be back,” I say. “Don’t go anywhere.”

How to Help

For more ways to support local businesses, go here.

For more on Marin:

- Water Therapy: Fitness For Mind and Body

- A Marin Home Gets Remodeled For Outdoor Living

- Keep the Olympic Spirit Going in Marin: Join the Marin Magazine Decathlon

Nancy Chung Hooper has lived in Marin for 25 years. After getting her master’s in journalism at Northwestern, she worked as a communication consultant. While raising two daughters with her husband Todd, she nurtured her interests in education and health care by volunteering at Marin Montessori School and the Global AIDS Interfaith Alliance, sharpened her tennis skills and is finally stretching herself with yoga. Known for her poetic holiday cards, she believes every person has a story worth listening to and writing about.