FOR DECADES MOUNT Tamalpais has been a patchwork of public lands, a quilt whose seams are only visible on a map. Technically that’s still true, but last March the four public agencies that own and manage Mount Tam’s 46,000 acres (the Marin Municipal Water District, Marin County Open Space District, California State Parks and the National Park Service in partnership with the Golden Gate National Parks Conservancy) formally gathered for the first time under a common umbrella, the Tamalpais Lands Collaborative.

“It became pretty clear that that was the way to go,” says Mike Swezy, watershed manager for the water district. “We get to do more of what’s needed, but certainly there’s a social aspect to it, and the collaboration among the agencies makes sense. It’s more efficient, more effective.”

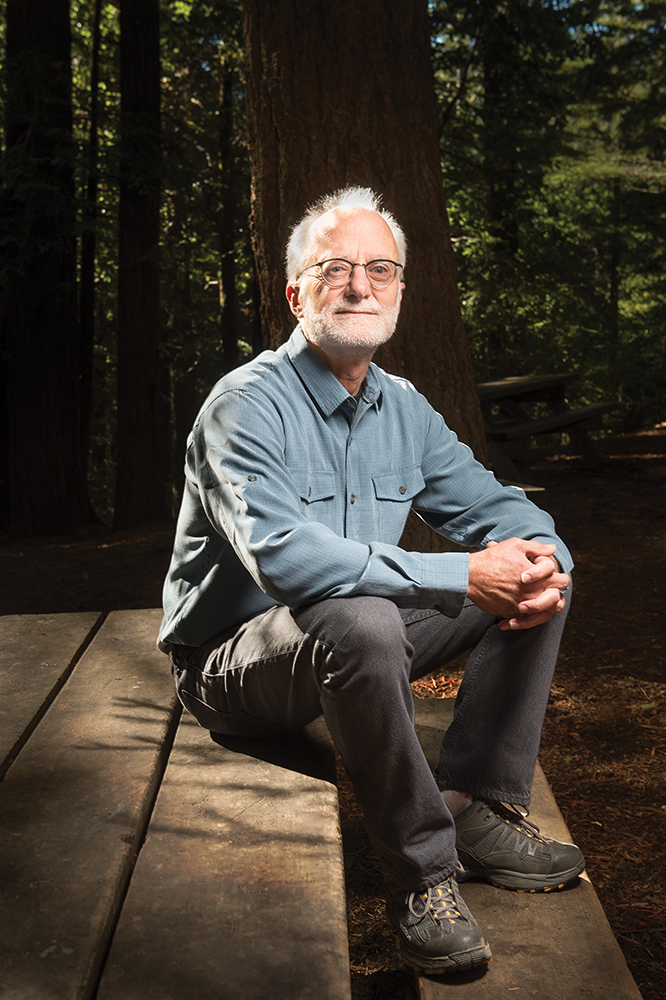

Marin resident Greg Moore serves as president and CEO — and has been at the helm for nearly three decades — of the collaborative’s fifth member, the Golden Gate National Parks Conservancy. The nonprofit organization partnered with the National Park Service in 1981 to support the Golden Gate National Recreation Area and its 80,000 acres, including Crissy Field, Alcatraz, the Marin Headlands, Stinson Beach, the Presidio and Muir Woods.

Now, thanks to its new role in the Tamalpais Lands Collaborative, the conservancy will also support conservation efforts across Mount Tam, which sees 1.8 million visitors every year. We talked with Moore about the history of the TLC and what it means for Marin’s favorite mountain.

First things first: how did we end up with four agencies and a nonprofit managing one mountain? It’s an interesting conservation history. The first piece was Muir Woods, which happened in 1908. It was threatened by logging and damming, and William Kent decided to buy it himself, and then donated it as the first gift of land to what became the National Park Service. His vision was to protect much of the open space of Marin County, in some type or form. So he was instrumental in saving Muir Woods, he was instrumental in helping save the water district lands and he took advantage of whatever route through which the place that he loved could be saved for the future. Ultimately we ended up with the watershed being established and the state parks coming in with Mount Tam State Park. The last piece came in 1972, when Marin County Open Space formed and began to designate lands around Mount Tam as open-space preserves. Also that same year, the Golden Gate National Recreation Area was created, and Muir Woods was folded into this larger national park.

What is the history of collaboration among them? We were lucky that in the beginning stage of thinking about this collaborative, there had already been decades of coordination among the different people involved. It came together in a more focused and long-term way when there was a collaborative plan developed for the Redwood Creek Watershed in 2003. Then something unexpected happened in 2012 with the state parks crisis and the potential closure of the Marin state parks. The park service reached out to help with that situation, adding an extra $2 admission fee for Muir Woods, to work in collaboration with the state parks to keep those sites open. Around the same time MMWD was thinking about how to bring in public support for its mission and even philanthropic giving for some of its priorities. And bit by bit as people talked, we began to see that although there was one mountain and it should have one vision for its care and stewardship, that there were four agencies and a nonprofit that could come together to take advantage of the community’s love affair with the mountain and to set some common goals for conservation and stewardship.

Were there any practical or logistical challenges with the previous arrangement that made this collaborative necessary? Sure. There was a growing acknowledgement that the stewardship obligations of the agencies, whether it was around invasive species, or trail repair, or restoration work, or even public enjoyment and understanding of the mountain, needed to work across boundaries. The trails didn’t stop at one line, nor did invasive species, nor did the need for restoration. And there was a realization that over time, each agency would have different resources, staff expertise and volunteers available, so there was strength in a collaborative, almost bringing the same diversity of a natural ecosystem to the care of the mountain. And also the belief that if we wanted to encourage volunteers to play a stewardship role, or contributors to make gifts to further the mountain’s stewardship, a model that showed collaboration and a single vision for the mountain would not only achieve better results, but would be more compelling to people giving because they could see that we had looked beyond our boundaries and to what’s best for the mountain.

Will there be anything imposed on any of the agencies, as far as balancing different needs or ways of doing things in order to achieve this collaborative focus? Nothing really is imposed. It’s really the belief that a collaborative structure can accomplish more. So for each agency, whatever public review process they have stays in place, whatever policies or guidelines they are bound by in the mission that fuels their work stays in place, yet within that the missions of all the organizations are very similar: to preserve the mountain for its benefits, whether water for the water district or biodiversity for the parks service, and to at some level allow for public enjoyment. There was pretty consistent mission overlap, and that gave us the comfort that we could create a common vision for the mountain.

So it’s about embracing those commonalities rather than forcing a middle ground — taking the existing points of agreement and fostering them. That’s a great way of putting it. Even if we restore part of MMWD or remove invasive species, often that has downstream positive effects on other land managers, because invasive species in one place carry over to the next. Or a trail that’s eroding into one stream, as that stream makes its way down through the watershed, it’s causing sedimentation. Or a hiker on one trail wants to know how to get to the next. So they’re really simple and obvious points of interconnection.

Can you tell us what’s happened in the last 10 months, and what’s under way that was brought about by the collaborative? There are a number of things — some that have been brought to conclusion and some that are under way. There’s been trail repair work on the Bootjack Trail and in a number of other places. There’s coordination on signage, and a complete inventory of all the signage, to make certain that as you cross between one or another jurisdiction that there’s a seamlessness in that visitor experience. There’s been quite a bit of vegetation mapping and invasive species mapping, just to understand collectively what we’re dealing with and how to handle it. And we’ve begun to consider, looking ahead, what projects and programs could not only be the priorities of the agencies in the collaborative, but bring community benefit as well. As you look at the mountain as each agency puts together what’s on its plate, it’s a big list. The conservancy’s role, including providing support to the overall effort in terms of staff and teamwork, is to help bring philanthropic funds in to the priority projects.

Was some of this work deferred due to challenges arising from the complex management environment? Yes, I think so. To some degree, when you want to go to scale with this work, it’s hard to do it alone. If you have more partners in there, believing in the outcome and providing resources to get there, and having the perseverance to get to the goal, you can accomplish a bigger ambition. Depending on the funding cycles of the different agencies, at times they may have a certain strength and at other times not, and the partnership will provide a more even approach to resources being in place.

Are you looking for volunteers yet for any of these efforts? Yes, we are. Previously volunteers were coming to us through each agency portal, so to speak. Our hope is that OneTam.org, launched in November, will be the new galvanizing force for volunteers. For anyone who wants to help Mount Tam, it’s hard to know where to go. There are almost too many choices. OneTam.org is a more user-friendly portal, and although the collaborative has primary partners, we’re also intersecting with the nonprofit organizations that have a proud history of conservation work on Tam as well. We need them too. They’ve provided a valuable role and we’re not trying to take that role, but to bring them in as part of the overall team.