courtesy of the marin independent journal

Some people were born to make history. Vera Schultz, the first female member of the Marin County Board of Supervisors, was one of those people. Schultz was a true pioneer for women’s rights in Marin County, but she was also a trailblazer in the fields of urban planning, environmentally sensitive design and social justice. Marin County would not have some of its most valuable assets if not for her legacy. It was for this reason that she earned the title “First Lady of Marin” during her six-decade career in public service.

A Political Spark

Vera “Bobby” Schultz was born in the rural desert community of Dutch Flats, Nevada, in 1902. Her passion for human rights had its roots in a childhood encounter. Her father invited all kinds of people to dine at the family table; one night, he entertained an elderly neighbor, an ex-slave named Ike, and a Southern woman boarding with the family refused to join them. “Then you’ll just have to have supper in your room, I guess,” Vera’s father said. Years later, when Schultz was fighting for quality public housing that would benefit African Americans (who had few other options) in Marin, she told this story to explain her commitment.

After finishing high school at age 16, Schultz enrolled at University of Nevada in 1920, majoring in journalism and working on the school paper. In 1924 she began graduate studies in English at UC Berkeley, eventually earning a master’s degree. Several years later in 1926, she married Ray Schultz, whom she met at University of Nevada; he joined her in Berkeley and became a San Francisco insurance agent. The couple built a summer cottage in Mill Valley, intending to stay just a few of months, but ended up moving there, partly for the weather. “When I first came to Marin in 1928, I just loved this place, so full of the beauty I used to long for when I was growing up in the desert,” Schultz recalled according to Evelyn Radford’s biography Vera: First Lady of Marin. “I thought I was in heaven here — I have been in heaven here.”

Schultz’s interest in politics and social reform began when she helped organize the local chapter of the League of Women Voters and attended every board of supervisors meeting for her first 10 years in Marin (a record few politicians could match). Her husband supported her political ambitions, she said in a 1981 interview in The Pacific Sun, “because he realized they were motivated by a deep interest in government, and a knowledge of it.”

During these years she worked as a bookkeeper for the local school district and campaigned for a new council-manager form of Mill Valley government, which voters approved in 1941. In 1946 she was elected to the city council — its first female member, and her first political office — beating six male contenders. Years later she told the Marin Independent Journal that the men on the council denied her the mayor’s seat, even though she’d won the most votes, which traditionally should have gotten her the job. She served on the council six years.

Path to Higher Office

In 1950, appalled by lobbyist influence and corruption in state government in Sacramento, Schultz decided to run for the California Assembly. She campaigned as a Democrat on a reform platform and lost; Marin County was heavily Republican at the time. In 1952 she was chosen as a delegate to the Democratic National Convention in Chicago, where she backed the reform candidate Estes Kefauver.

That same year, she ran for an open seat on the Marin County Board of Supervisors. At the time the Ladies Home Journal featured her in an article on women delegates, boosting her campaign, and in November the initial tally had her winning by 165 votes. But the losing candidate asked for a recount and, in a scenario reminiscent of the 2000 U.S. presidential election, scores of Schultz’s votes were disqualified for ballots allegedly hard to distinguish, while dozens of counted absentee votes for her opponent had been improperly sealed with Scotch tape rather than sealing wax as required at the time.

Schultz filed a complaint, and a county judge ruled most of her original votes should be counted, winning her the election. Her swearing-in took place in the hallway, while the men took the oath inside council chambers.

courtesy of the marin independent journal

During her two terms as supervisor, Vera Schultz led the fight for many of the reforms and services Marin County residents take for granted today. Initially she had to battle the entrenched power of the “Court House Gang,” a group of male civic leaders who resented any attempts at change, especially led by a woman. Nonetheless, Schultz prevailed in almost all her efforts.

One of her first proposals moved to establish the office of County Administrator to bring business management skills to the complex activities of government. She went on to help create a County Personnel Commission, which would pick the most qualified people for county jobs and end the corrupt spoils system. She also worked to establish the County Parks and Recreation Department, as well as the public works department and a county counsel’s office. Schultz helped modernize county government operations by introducing data processing and central purchasing. The voters clearly supported her efforts: she was reelected in 1956 by a two-to-one margin.

Two Signature Projects

In her second term she introduced two important projects with overlapping timelines: construction of the Marin County Civic Center and the housing development now known as Marin City.

In the early 1950s, Marin County’s fast-growing population was ill served by county offices in 12 scattered locations and an antiquated courthouse in downtown San Rafael. Schultz advocated for a new courthouse complex, and in 1953 supervisors began seeking a site. They settled on a private ranch just east of Highway 101 and interviewed architects; in 1957, four of the five supervisors agreed to draw up a contract with Frank Lloyd Wright. Schultz was Wright’s strongest proponent, enthusiastically championing his then-radically modern design. But Supervisor William Fusselman, together with County Clerk George Jones, vehemently opposed using Wright and attempted to block the plan, in a battle royal that lasted four years.

At a supervisors’ meeting August 2, 1957, held to formally approve Wright’s plan, Fusselman asked to have a report on Wright by an investigator for Sen. Joseph McCarthy read into the record. It accused Wright of “active and extensive support of communist views and enterprises.” Wright stormed out of the meeting: “This is an absolute and utter insult, and I won’t be subject to it!” he declared.

Deploring the accusations, Schultz said, “This county does not look into the political beliefs of any of its employees. It certainly is inappropriate that we should subject a man of Mr. Wright’s caliber to such unfounded and unsubstantiated charges.” In the end, the report was never read into the record, Wright’s plans were approved, and the contract with him was signed by the four supervisors. Fusselman kept trying to thwart construction, in vain: a majority of Marin residents supported the project. Today Wright’s environmentally sensitive design, with its graceful bridging of two hillsides and nature-based colors, is considered one of the finest public buildings in the United States by architects and critics around the world.

The Marin City project, Schultz’s other major feat, was innovative for its time, one of the first experiments in racially integrated public housing in California. During World War II the site, not far from the Sausalito waterfront, held temporary U.S. government housing for shipyard workers. After the war, the land by law had to be offered back to the county or for sale on the open market for future development.

The Marin City project, Schultz’s other major feat, was innovative for its time, one of the first experiments in racially integrated public housing in California. During World War II the site, not far from the Sausalito waterfront, held temporary U.S. government housing for shipyard workers. After the war, the land by law had to be offered back to the county or for sale on the open market for future development.

As the site’s wartime housing was rapidly deteriorating, Schultz saw an opportunity: to create a new kind of community there, a racially harmonious neighborhood with low-cost and middle-income housing for thousands of residents. During the war the housing held a roughly equal mix of blacks and whites, but afterward most of the whites left. The black residents were unable to move, constrained by financial hardship and racist clauses in real estate covenants that prevented them from buying homes across the county.

Evelyn Radford’s biography describes how Schultz overcame opposition to the project within county government; her opponents were the same ones she would face in her Civic Center battle — Fusselman and Jones.

Jones fired the first volley, writing dozens of letters to the Housing and Home Finance Commission in Washington, D.C., the agency that would turn the site over to a new owner. He told the commission to ignore letters Schultz had sent on behalf of the supervisors, saying he had a buyer who would pay “above current value” for the land. When Schultz called the commission’s office to see why all her letters were being ignored, she was told to come to Washington right away. When she got there, she read the letters from Jones and was shocked. Schultz quickly reminded the commissioners of the law requiring the government to offer the land to the county first, charging that Jones was trying to manipulate the process for his personal gain.

Back in Marin, Schultz confronted Jones, who couldn’t deny his actions. The board merely reprimanded him for using county stationery for personal correspondence rather than conduct a formal inquiry as Schultz favored; still, the U.S. government turned the land over to the Marin County Redevelopment Foundation in 1956. Aaron Green, an associate of Frank Lloyd Wright, designed 300 units of housing built over the next six years; famed landscape architect Lawrence Halprin designed most of the outdoor common areas.

A Political Exit

In 1960, in part to help pay for the civic center, the county reappraised property taxes, and Schultz’s district was first to have its taxes raised. Many voters blamed her, and she lost her bid for a third term that year. “That was the low point of my life,” she told the Marin IJ in 1981. “I had really enjoyed being a supervisor. We were paid $150 a month in those days, so it never was the money — it was the opportunity to do some good.”

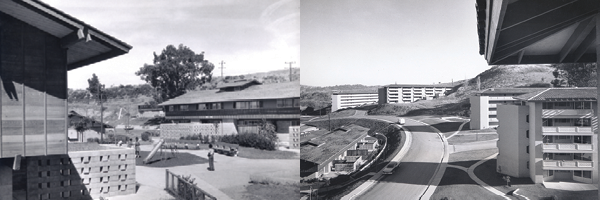

Courtesy of Aaron Green Associates

The two-story Marin City units with landscaping in place and kids enjoying the play area (left); Marin City high-rise towers as they looked right after construction around 1960 (right).

Yet she remained active in county government and public affairs. Although she never held office again (losing a state senate bid in 1964), her list of late-inlife accomplishments is impressive. She served on the boards of the Marin Housing Authority and Marin Redevelopment Agency, led the bond campaign to create Marin General Hospital, helped create the Marin Senior Coordinating Council, was a delegate to the White House Conference on Aging in 1965, and helped create several public parks and Marin’s first school for disabled children.

Schultz became blind during the last several years of her life, but kept informed on current events by hiring a secretary to read several newspapers to her every day. She moved to Texas in 1995 to be with her daughter, son-in-law and three grandchildren and died shortly after, at age 93.

Perhaps the best assessment of Vera Schultz’s legacy is her own remark, a comment made in 1983 to the Pacific Sun but just as relevant today. “Before women can be expected to change the world, they have to be firmly anchored in it,” she said. “We are still marginal. The most important thing to both men and women is that when women are more equal, it completes men too. It’s going to be better for both. It isn’t that women gain by taking something away from men, but women gain by being more truly men’s partner. This is the best thing for a family, and it’s the best thing for society. That’s what lies ahead.”

Additional research provided by Ania Skulimowska.