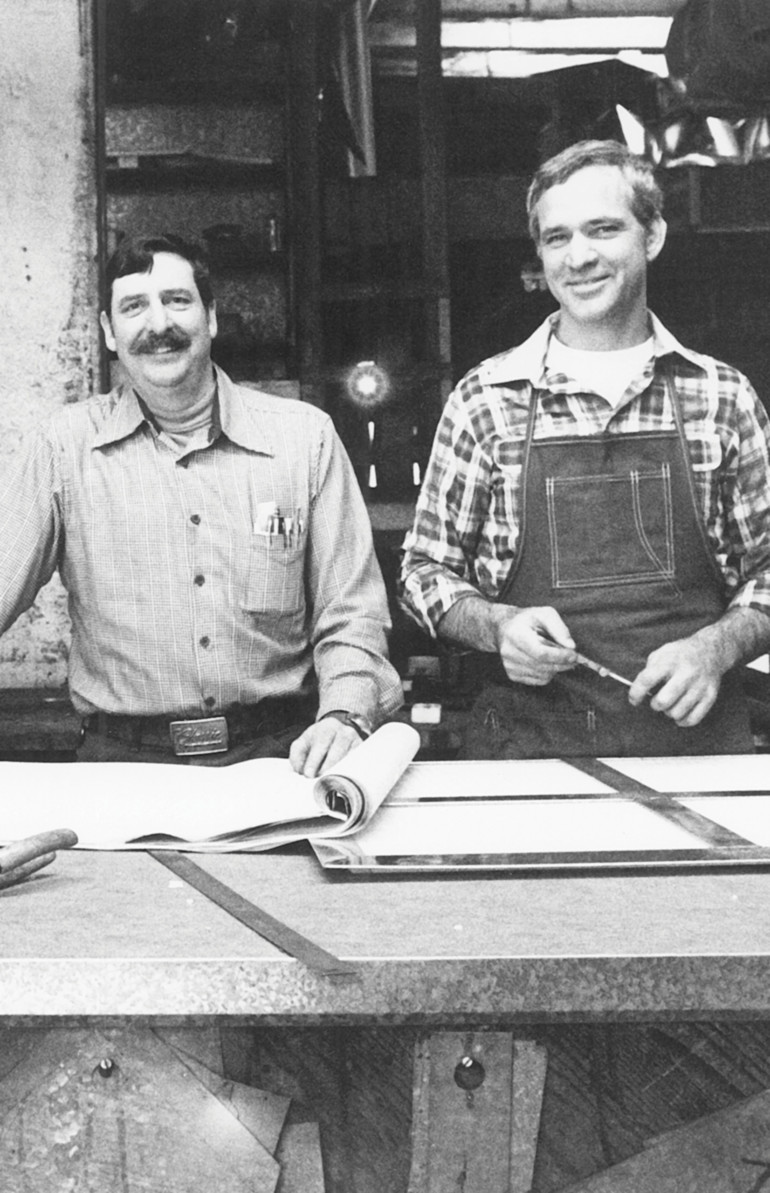

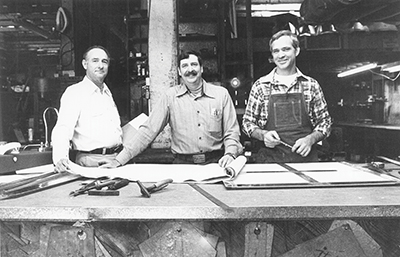

Don, Ernie and Rich Ongaro.

WHEN ERNEST ONGARO, who founded the heating and plumbing company Ongaro and Sons in 1932, decided to hand down his San Anselmo business to his sons and grandsons, he set one rule in place: If you want to be on the family payroll, you need to work someplace else first.

“The reason was simple,” says Dean Ongaro, a third-generation owner. “Everyone should work for a crummy boss at least once. And if you want to appreciate something, see what it’s like working for someone else.”

Ernest was wise: The company is now run by four of his grandsons. And though splashy national headlines tell of epic family business battles (see: the Koch brothers or pretty much any of the Murdoch clan), the truth is such companies can be pretty good places to work. “There are a lot of advantages to working in a family business,” says JoAnne Norton, Ed.D., an Irvine-based consultant with the Family Business Consulting Group, “and there are so many more families who work together harmoniously than the ones who don’t.”

By definition, family businesses combine the two things that make people the most happy and drive them the most crazy. What’s surprising, though, is that they actually perform better than nonfamily enterprises. According to Norton, who taught a class on family businesses at Cal State Fullerton, the average life expectancy of a company in the U.S. is 12 years, but for family-run concerns, it’s 24.

Marin is home to a number of such businesses, especially if the surname happens to be Italian: Ghilotti, Giacomini, Ongaro, Brusati, Ghiringelli. While the county does not keep statistics on family businesses, we’re probably in line with the rest of the country. According to the Small Business Administration, 90 percent of all businesses nationwide are family owned. That includes everything from behemoths like Wal-Mart to midsize construction companies to grocery stores like Paradise Foods in Corte Madera, Tiburon and Novato.

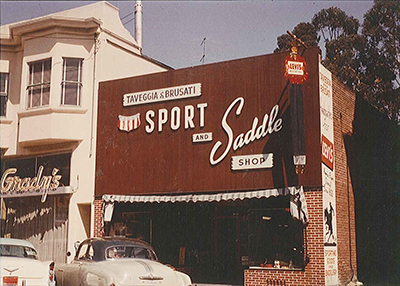

“One of the greatest advantages of working in a family business,” says Jeff Brusati, a second-generation owner of T & B Sports in San Rafael, “is that you get to work with people who are important to you.” Brusati, who co-owns the company with his brother Mike, also employs his son Anthony, 31, in sales. “It’s a true family affair; we all support each other and help each other as much as we can.”

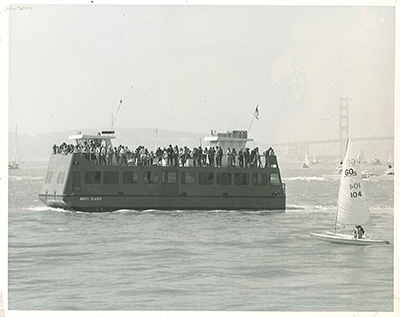

There are a lot of reasons family businesses thrive. The first, says Norton, is that people are often groomed for their jobs from childhood, earning a “kitchen table MBA.” Or in Maggie McDonogh’s case a kitchen table captain’s license. McDonogh, a fourth-generation owner of the Angel Island Ferry, grew up working alongside her father, Milton, learning how to pilot and maintain the boat. As a mother she is training own kids — or “potential ferryboat captains” as she calls them — in turn. When Sam and Becky (now 19 and 12) were babies, she carried them in a BabyBjorn while ferrying passengers across the bay. When they were toddlers, she kept a playpen in the wheelhouse. And when they were old enough to argue with each other — along with her stepson, Ben, now 8 — she used the public announcement system at least once to yell at her kids, “Don’t make me stop this ferryboat!” Customers still remember that one.

Other business owners forged their working relationships by playing together as kids. Mitch Ongaro says he, his brother Dean, and their cousins Ernie and Paul work well together because they spent so much time fishing and hunting as kids at their grandfather’s ranch in Napa and continue to take such trips even now. “I know hunting and fishing aren’t politically correct, but when we go on these trips, we figure stuff out,” says Mitch. “When we were little, we’d be on the ridge at 5 a.m., and we’d have to trust each other completely, or we’d get lost. We just learned to get along.”

The Angel Island Ferry as it looked in 1975.

Of course, family members don’t always get along, which can get a little sticky. So how do they resolve conflicts? In a slightly different way than, say, a contentious corporate board meeting. When the four co-owners of Ongaro and Sons were deciding, in the early 1990s, whether to abandon the retail part of their plumbing business, Ernie, the president, presented his relatives with a stack of paper showing that it made no money. Dean, however, was adamant they keep it, because it created goodwill in the community. They held a family meeting and Ernie asked, “What’s it going to take for you to see this is a loss?” “A new Toyota truck,” Dean replied. “What else?” Ernie prodded. “Fourdoor, four-wheel drive,” Dean replied. To which Ernie said, “Done,” and away went retail. After it all ended, Mitch — who had sided with Ernie — thought, “Son of a bitch, I should have argued for a truck.”

Some families, like the Giacominis, who’ve owned Toby’s Feed Barn in Point Reyes Station for three generations, take a more sanguine approach to conflict. “We all do yoga,” says Nicholas Giacomini, a family member who’s better known now as the yoga hip-hop artist MC Yogi. And if that fails? “Then we do Pilates and yoga.”

Working with family can also lead to a few blurred lines, which sometimes drives Maggie McDonogh’s fiancé (and business partner) William Bryerton a little crazy. “I’m the type of person who has things bouncing around in my head until I can get them out,” says McDonogh, “and it will be nighttime and we’ll be in bed, and poor William will ask me, ‘Do we have to talk about this now?’ and I’ll just say, ‘I have to talk about this; I have to get it out of my head.’”

It’s this level of nonstop commitment, though, that accounts for some of family businesses’ success, Norton says. Brusati knows that well. He dropped out of college just one semester shy of graduation to take over T & B Sports after his dad died in 1978. And when the stores get busy, he sheds his owner hat, “and I work side by side with everyone on the retail floor, or work the front register if needed.”

Family businesses offer what Norton calls agility, meaning that they can get things done without endless meetings; competent people can be promoted quickly; and work schedules can be flexible. Like the day last summer when the salmon were running, and Dean and Paul Ongaro decided to play hooky for a day to go fishing, leaving the operation to their relatives and their employees, all people they knew they could trust. It’s pretty common in family businesses for even non-related employees to be considered family. Except for seasonal businesses like the Angel Island Ferry, they tend to hire employees and keep them. At Toby’s Feed Barn, the general manager, Oscar Gamez, has been with the Giacominis for 25 years. The assistant manager, Laura Takahashi, has been employed by them for 20.

At the end of the day, it all comes down to commitment, which is a lot stronger, says Dean Ongaro, “when your name is on the business.” And, says Norton, whether the company is big or small, people are more willing to make sacrifices, earn a little less money and work harder “when they have to face their shareholders at the Thanksgiving table.”

Which leads to the most important question of all: When the family gathers around for Christmas cioppino, a bottle of red wine, and memories and laughs, what matters most, family or business? “Family, no question,” says Nicholas Giacomini. “At the end of the day, the business is just a building.”