A NEW BARNLIKE SAINT HELENA GUESTHOUSE by architect Ross Anderson, whose influential mentors William Turnbull and Charles Moore helped design eco-centric Sea Ranch, was created, in the age-old democratic spirit of barn raising, by and for many people.

A NEW BARNLIKE SAINT HELENA GUESTHOUSE by architect Ross Anderson, whose influential mentors William Turnbull and Charles Moore helped design eco-centric Sea Ranch, was created, in the age-old democratic spirit of barn raising, by and for many people.

Anderson’s slender, rectilinear, cedar-clad two-story structure, with a red painted rollaway front door, has a standing- seam zinc-coated steel roof that echoes gabled agrarian buildings in the valley. But sitting on the northern edge of a relatively small vineyard lot, it is in fact a 2,000-square-foot multiuse pavilion for a San Francisco lawyer and his wife who host sit-down dinners for crowds of as many as 60.

“They had a very complicated program for such a small space, and at first it sounded like a nightmare,” admits the architect, whose New York firm, Anderson Architects, typically tackles roomier hotel projects, as well as Bay Area wineries like Ravenswood.

“I had to essentially design a giant Swiss Army knife,” Anderson says, because the owners also desired an adjoining garage that could function as a basketball court for their son, and they wanted a hot tub for their daughter, another entertainment space outdoors and a place to set up more cooking facilities for big parties.

To fit in all that, he leaned on his early training. “Bill Turnbull always said, ‘look at the landscape first and let it dominate and thread it through,’ ” Anderson recalls. And that’s what he did, visually and literally, to expand the footprint.

“I started with the land and asked some questions,” he says. “Where should it be within the property? The answer was that it had to be at a distance from the main house, adjacent to the vines, where it could hide a neighbor’s building from view and also make room for a central meadow. How high, and how much volume do you need for a basketball court? Those dimensions set the ridge height, and the building took on the form of a large Napa Valley barn to fit right in near existing redwood trees.”

The building materials, including integrally colored cement floors embedded with radiant heating, were picked “for this hardworking structure because they are all low maintenance and will age well within this landscape,” Anderson says. Inside, he chose naturally patterned surfaces such as whitewashed plywood walls and blocks of native stone for a dramatic floor-to-ceiling fireplace, and he revealed the aggregate here and there in the polished concrete floor.

The building materials, including integrally colored cement floors embedded with radiant heating, were picked “for this hardworking structure because they are all low maintenance and will age well within this landscape,” Anderson says. Inside, he chose naturally patterned surfaces such as whitewashed plywood walls and blocks of native stone for a dramatic floor-to-ceiling fireplace, and he revealed the aggregate here and there in the polished concrete floor.

To be further integrated into its setting, the finished building is gently angled in the middle in a V-shape plan that forms a sheltered courtyard abutting the open meadow of wildflowers and grasses. It is gracefully shaded by a cherished mulberry tree that was preserved, and the building, thanks to its structure of independent Douglas fir roof trusses, is “sliced and diced easily to create large door openings, high windows and skylights to link it to the outside,” the architect says.

The rear wall has few openings because it abuts another structure and one of two galvanized irrigation water tanks (dubbed Rosso and Blanco by the owners, who grow merlot and other grapes on the property) that store harvested rainwater. However, in the front, the central space that houses a generous living room, dining area and a state-of-the art skylit kitchen can be thrown open completely to the courtyard when its NanaWall doors are folded away. Sunshine pours in from a southerly direction, and on slightly windy days, a large diaphanous curtain of sheer fabric can be pulled across the opening. The exposed beams and trusses form a soaring double-height space; here, sparse furnishings, including a sofa on casters and a round zinc and wood dining table for eight selected by interior designer Jean Larette, can be easily cleared away to provide a tentlike dining space for gatherings that can also spill out into the concrete courtyard surrounding the mulberry tree.

For this party venue, and as a nod to the tradition of great European banquet halls in medieval-era castles, Anderson’s design also incorporates a hidden stair to an upstairs minstrel’s balcony that overlooks the central space. On the west wall of the living area, a door leads to the garage that doubles as the desired basketball court and all-purpose outdoor gym,  temporary kitchen and bandstand. So that it stays cool, its side walls are simply widely spaced vertical slats of cedar that, like those of real barns used for drying hay or lavender, allow air to flow naturally through the gaps.

temporary kitchen and bandstand. So that it stays cool, its side walls are simply widely spaced vertical slats of cedar that, like those of real barns used for drying hay or lavender, allow air to flow naturally through the gaps.

On the east side of the building, a chunk of roof facing the front is cut away to reveal an upstairs sleeping porch just above two ground-floor bedrooms adjacent to the kitchen.

“That room upstairs is incredible and a surprise. When Ross mentioned the porch I thought, ‘Who will want to use that?’ ” the wife says. “We were also concerned about the owls, jackrabbits and bobcats getting in somehow, but it has never been an issue.”

On the contrary, “we wanted to encourage bees, bugs and rabbits everywhere,” Anderson says. “We wanted to maintain and magnify a rural quality.”

Even during the drought, that proved relatively easy, because hardy native grasses that were introduced in the meadow grow well, thanks to the high water table near the Napa River.

“Although the building is so exposed to the elements inside and out, it can be locked up and easily reopened completely to this natural setting,” Anderson says, pleased. “Just like a Swiss Army knife, it is a closed shape that opens up when you really need to use it.”

View the gallery below for more photos.

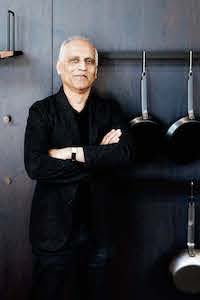

Zahid Sardar brings an extensive range of design interests and keen knowledge of Bay Area design culture to SPACES magazine. He is a San Francisco editor, curator and author specializing in global architecture, interiors, landscape and industrial design. His work has appeared in numerous design publications as well as the San Francisco Chronicle for which he served as an influential design editor for 22 years. Sardar serves on the San Francisco Decorator Showcase design advisory board.