ON that October late afternoon, Allen Fish was in his office at Golden Gate Raptor Observatory in the Marin Headlands. It was migration season, and Fish, the observatory director, had volunteers out tracking hawks. “Most had gone for the day,” he recalls. “But there were a few people still out. I was waiting on them. Then the shaking started.”

Fifteen miles south, Greenbrae resident Rich Swanson and his girlfriend (now wife) Maradee Davis had found their seats at Candlestick Park and were waiting for the third game of the World Series — San Francisco versus Oakland A’s — to begin. “At first the shaking wasn’t that intense,” Swanson remembers. “I thought people were stamping their feet. But it got stronger. I realized, this is a big quake.”

Halfway across the planet, Lisa Taggart stood at a pay phone in Cairns, Australia, making a surprise call to her mother in San Anselmo. A Harvard junior, Taggart was spending a term abroad studying cane frogs. “Our camp was in the jungle an hour away,” Taggart recalls. “We were on semester break, so we got to go into town. I hadn’t talked to my mother since September — this was before the internet, before cellphones. I was excited.”

In her kitchen in San Anselmo, Mary Beth Taggart picked up the ringing phone. The house began to tremble. “It was very hard shaking,” she remembers.

“The connection was noisy and weird,” Lisa Taggart says.

“I said, ‘Mom, it’s me.’ ” “I said, ‘There’s an earthquake,’ ” Mary Beth Taggart recalls. “I need to get off the phone.”

It was 5:04 in the afternoon, Tuesday, October 17, 1989. What Allen Fish (no relation to the author), Rich Swanson, Maradee Davis, and Lisa and Mary Beth Taggart were experiencing was the Loma Prieta earthquake, 6.9 on the Richter scale, although at that moment neither the quake’s magnitude nor the epicenter that would give it its name were yet determined. The quake lasted approximately 15 seconds. It was the most powerful to strike the Bay Area since 1906. It would shatter downtown Santa Cruz, set fire to San Francisco’s Marina District, pancake a section of I-880 in Oakland and partially collapse the Bay Bridge. It would cause 63 deaths and 3,753 injuries and do an estimated $10 billion in damages.

Thirty years after that October afternoon, Marin County and all the Bay Area still feel the effects of Loma Prieta. On its 30th anniversary, earth scientists probe the forces that generate temblors like Loma Prieta and, more recently, this summer’s Ridgecrest and 2014’s Napa. We non-scientists ask ourselves, when and where will the next big quake hit? When it does, what do we do?

What We’ve Learned — and What We Haven’t

Seismologists quickly determined that the epicenter of the October 17 earthquake was in the Santa Cruz Mountains, near a peak named Loma Prieta (in Spanish, “dark hill”). The quake struck on a segment of the San Andreas Fault, the roughly 800-mile-long fault zone that runs two-thirds of the length of California, starting near the Salton Sea and ending off the Mendocino coast. Even people who don’t know much about earthquakes know about the San Andreas: that it has generated many of California’s biggest quakes, including the San Francisco cataclysm of 1906; that it is the product of two continental plates, the North American and the Pacific, sideswiping each other like two SUVs in a parking lot. And that it has sculpted some of California’s most beautiful landscapes — including Marin’s, because the fault slices through the western third of the county, entering near Bolinas, following Tomales Bay and Highway 1 north and plunging back into the ocean near Dillon Beach.

The San Andreas is also, says Ross Stein, scientist emeritus at the U.S. Geological Survey and consulting professor of geophysics at Stanford University, “one of the most studied faults in the world.” Indeed, Stein adds, the San Andreas has been poked and probed so much it’s like a worn-out children’s toy. “It’s the Velveteen Rabbit of earth science. We love it so much its eyes have popped out.”

What have scientists learned about the San Andreas since Loma Prieta? A lot, says Stein — and much of the new knowledge came from studying the 1989 quake. One big discovery, he notes, is that “earthquake faults don’t operate in isolation — they influence each other. Right after Loma Prieta we saw profound changes in the South Bay. The Calaveras Fault turned off. The San Gregorio Fault turned on. Understanding these quake conversations is one of the most powerful tools we’ve developed in the last 30 years.”

Other advances are technological. To understand earthquakes you need to know — very precisely — how and where the ground has moved in a quake, and how the ground might be storing up energy for a future quake. Earth scientists now get these precise measurements by using satellites to bounce radar off the earth’s surface. “Our techniques have gotten better and better,” says Howard Zebker, a Stanford professor of geophysics and electrical engineering, who helped develop the method while at Pasadena’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in the 1990s. “In principle, when we know where the energy is being stored, we can say which places are more likely to have an earthquake and which places less.”

And yet despite these advances, our understanding of earthquakes remains frustratingly incomplete. Take a basic question — what triggers big earthquakes? “One theory,” Ross Stein says, “is that any little quake has a small probability of cascading into a larger quake. Another is that there’s something unique about conditions on some faults that make them more likely to produce big quakes.” We still don’t know which theory is correct, and that and other uncertainties mean that while we’ve gotten better at estimating general quake risks, we’re a long ways from making more specific time and place predictions. When it comes to those, says Stein, “We have to acknowledge that all our efforts have failed miserably.”

The Big Decisions: Insurance and Retrofits

Which leaves us … where? The California Earthquake Authority estimates that Marin — vulnerable to quakes on both the San Andreas and Hayward faults — has a 76 percent risk of experiencing a 7.0-plus quake in the next 30 years. But it’s not as though we can add the event to our Google calendar: November 12, 7.1 quake centered in Bolinas.

Ross Stein says that doesn’t matter — understanding the general risk is more useful. “When you think about it,” he says, “if you predicted a 7.0 on the Hayward Fault one week in advance, everybody would leave. Lives would be saved, but everything would be destroyed.” A far better option, he believes, is knowing where quake risks are the highest, then building structures that “can withstand anything the faults can hurl at them.”

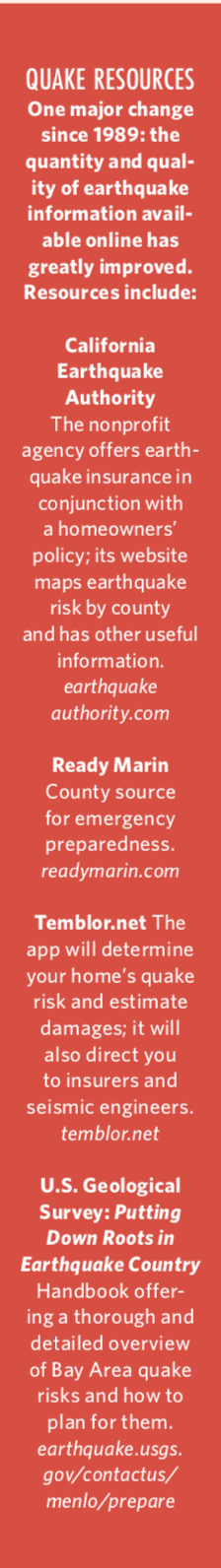

Stein is pushing that process forward with Temblor, a new app for iPhone, Android and the web he developed with Turkish geophysical engineer Volkan Sevilgen. Give Temblor your info — including home address and your home’s age — and it will estimate how vulnerable your property is to a quake, even how much monetary damage you’re likely to suffer. “We wanted everybody with a cellphone on earth to know their risk,” Stein says.

Temblor also provides guidance on the two toughest quake deci- sions homeowners face: buying (or not buying) earthquake insurance, and how to seismically retrofit their home.

“Whenever there’s a big quake, like the one in Ridgecrest, I get a lot of calls about insurance,” says Stephanie Cannell, a Farmers Insurance agent in Mill Valley. (The California Earthquake Authority reported that it sold 23,861 new earthquake insurance policies in July, the second-largest monthly net increase in its 23-year history — interest presumably generated by the Ridgecrest quake.) Earthquake insurance exists because standard homeowners’ policies don’t cover quake damage. Currently, only about 10 percent of California home- owners carry such coverage, in part because policies have had the reputation of being expensive — average premiums run about $800 a year — and of coming with high deductibles. But policies offered by the CEA — a nonprofit agency founded after the 1994 Northridge quake — have improved the situation, Cannell says: “They offer more deductible options and are easier to customize.”

Seismic retrofitting can also be complicated. Mel Victor, of Marin- and San Francisco–based Victor Construction and Engineering, says that even houses built as recently as the 1970s may be vulnerable to quakes, especially if — as is common in Marin — they’re built on a hillside. As for retrofit cost, “the average can be all over the board.” Unfortunately, that’s because “a lot of people opt to do the minimum and they choose contractors who don’t do a good job,” Victor adds. Bolts and foundation plates to anchor the house to its foundation are retrofit essentials, he says, as are, frequently, shear walls that add structural integrity. Look for local contractors with good internet reviews, Victor advises, and expect to pay anywhere from $25,000 to $100,000.

“Let’s get out of here”

The Loma Prieta quake let Marin off relatively easy. Damages in the county were $1.6 million of the $10 billion Bay Area total. No fatalities occurred in the county itself, although three Marin residents died in the collapse of Interstate 880.

Still, for Marin residents who went through it, Loma Prieta memories remain indelible. After the shaking stopped, Rich Swanson and Maradee Davis shuffled with 62,000 other baseball fans out of the stadium into Candlestick’s parking lots. “We heard on somebody’s radio about the Bay Bridge, about the Marina being on fire. I said to Maradee, ‘Let’s get out of here.’” It took them six hours to drive the 15 miles home.

In Australia, Lisa Taggart tried calling her mother Mary Beth later that day but was unable to get through. In Cairns bars, televisions showed alarming news: 10,000 feared dead in San Francisco quake. “I wasn’t able to reach my mom for three days,” Taggart says. “By then the news had been corrected — [fewer] than 100 dead.” Allen Fish rode out the quake at the Raptor Center. “One of the volunteers was listening to the radio and he said the Bay Bridge was down.” Fish’s father had been with him earlier in the day, had driven over the Bay Bridge and just exited 1-880 in Oakland in time to watch the freeway collapse behind him. “It was scary,” Fish says. “It affected him for weeks.

“So many of the roads were blocked,” he adds. “I had nowhere to go. I drove up to Hawk Hill. There were about a hundred of us there. We could look through the Golden Gate Bridge and watch the Marina burn. None of knew what to do. We were just bearing witness.”

As we’ll do the next time. And there will be a next time.

Peter Fish has been writing for thirty years for publications such as Sunset Magazine, the San Francisco Chronicle and AFAR. His Sunset Magazine article on the reintroduction of wolves to Yellowstone National Park, “Howl,” won a 2013 Lowell Thomas Award gold medal for environmental journalism. He lives in San Francisco with his wife and son.