The rain began as a cordial drizzle, but steadily thickened, soaking us through the rotten soft shell of the Russian jeep as we bounced along in second gear. Across the river border, Afghan mule trains animated an otherwise stark mountainside, clinging to ancient trails along the Panj River, and drawing contrast with Tajikistan’s Soviet legacies, including the Pamir Highway itself. Leaving its dilapidated asphalt behind, we took to dirt and veered into the sweeping Bartang Valley beneath a corridor of 17,000-foot peaks. Here in this sparsely populated corner of southeastern Tajikistan, I was beginning to discover a fascinating confluence of landscape, culture and history.

Tucked between Afghanistan and the western reaches of China, Tajikistan is a little-known Central Asian gem. Convening at the doorstep of its legendary Pamir Range is a who’s who of the world’s greatest mountain ranges: Himalaya, Hindu Kush, Karakoram, Kunlun, and Tien Shan. While the eastern Pamir Range contains a vast high-altitude plateau reminiscent of the nearby Tibetan plateau, the Bartang Valley is a classic specimen of the western Pamir: a contortion of steep river gorges sculpted by glacial whitewater. Tajikistan’s rugged terrain provided a measure of insulation from the major political and military events throughout Central Asia’s early history, allowing the Tajiks to retain their Persian heritage in a region dominated by Turkic influence.

Entering the Bartang Valley, we were now several hours north of Khorog, the provincial hub that serves as a sort of gateway between the eastern and western Pamir. From Khorog, about a two-day drive from Tajikistan’s capital city of Dushanbe, the Pamir Highway separates from the river border with Afghanistan and tracks east onto the desolate plateau inhabited by yurt-dwelling Kyrgyz. The plateau eventually leads to China’s western Xinjiang province. But before continuing east, I was intent on exploring one last feature of the western Pamir: the Bartang Valley.

My driver spoke the Indo-Iranian languages of Pamiri and Tajik, then Russian, and fragments of English. His anxiety was unspoken but palpable, being well acquainted with the effect that rain has on the scree slopes of the Bartang Valley. Soon we encountered our first major landslide, a sluggish effluence of mud and rocks several feet deep. A Russian minibus full of local families joined us at the bottleneck, and soon men from a nearby village appeared to help clear the path, shovel by shovel. Well accustomed to arduous overland travel, the Pamiris approach such adventures with a lively spirit of camaraderie.

My driver spoke the Indo-Iranian languages of Pamiri and Tajik, then Russian, and fragments of English. His anxiety was unspoken but palpable, being well acquainted with the effect that rain has on the scree slopes of the Bartang Valley. Soon we encountered our first major landslide, a sluggish effluence of mud and rocks several feet deep. A Russian minibus full of local families joined us at the bottleneck, and soon men from a nearby village appeared to help clear the path, shovel by shovel. Well accustomed to arduous overland travel, the Pamiris approach such adventures with a lively spirit of camaraderie.

Darkness descended as we progressed up-canyon on desperate allowances of road flanking the swift and icy Bartang River. We stopped briefly in a small village to visit with the driver’s extended family, who rushed in from nearby fields to stoke their woodstove and prepare hot tea. The hosts being wet and muddy from their daily chores tending goats, ourselves wet and muddy from clearing landslides, we took mutual pleasure in the comfort of a dry home. After warming up with tea and conversation, we resumed our journey having acquired several goats, which joined me in the front seat with tethered hooves. Beyond the last remnants of twilight, we arrived in the village of Basid, where my driver graciously arranged for me to stay with his brother’s family, and I began to experience the remarkable hospitality of the Pamiri people.

At first light, I awoke on a bed of richly decorated carpets. The Pamiri home is simple and cozy, with each element steeped in Aryan, Buddhist, Zoroastrian, or Islamic symbolism. The skylight and its concentric squares represent earth, water, air and fire, known locally as the “four houses.” Surrounding the skylight, five supporting pillars stand for Muhammad, Ali, Fatima, Hasan, and Husayn, as well as the Five Pillars of Islam.

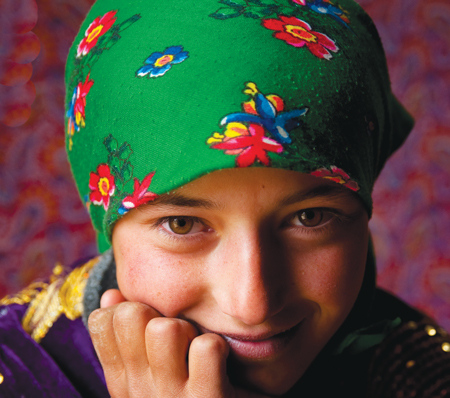

The Pamiris are predominantly Ismaili Muslims, whose geographic nexus occurs in this historic region of Badakhshan, extending from southeastern Tajikistan into northern Afghanistan and Pakistan. At the core of Ismailism is Prince Aga Khan IV, the imam whose religious leadership provides a living interpretation of the Koran. The Aga Khan’s embrace of women’s rights and education has fostered a uniquely progressive orientation among the Ismailis, whose peaceful communities constitute a foundation of stability in one of the world’s most polarized regions.

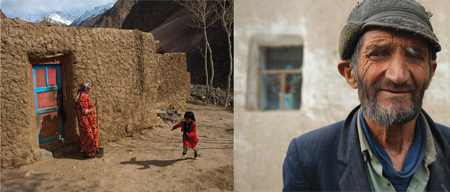

My hosts greeted me with a pot of black tea, a warm loaf of bread, and a heaping plate of potatoes. A sunny morning was not to be taken for granted, so after breakfast I hurried out to explore the village with my camera. Clusters of mud-walled homes were interspersed within fields of wheat and apricot orchards. Women in colorful full-length dresses and headscarves led their sheep and goats to pastures on the opposite side of the Bartang River, navigating a precarious “bridge” of two cables overlaid with brittle sticks, and a conspicuous lack of anything else to prevent a plunge into the swirling rapids below. For the moment, I was content not to attempt it myself, as the scenery alone captivated my attention, and I quickly developed an admiration for life in this mountain paradise.

After a few days in Basid, I recruited my jeep driver to take me deeper into the Bartang Valley, to a hamlet known as Bardara. Similar to its neighboring villages, Bardara is perched atop a giant alluvial fan spilling down from precipitous peaks and spanning the width of the river canyon. As we puttered up to the edge of the alluvium on switchbacks, over 40 villagers amassed to usher me through their maze of turf pathways, gurgling water canals, and bursting apple blossoms. It was simply the loveliest place I had ever visited. But it was soon apparent that the warm nature of Bardara’s residents easily surpassed the appeal of its physical beauty. To accept each household’s invitation for tea would have consumed weeks; at last, I embraced their hospitality, staying five days with one family, and having tea with many others.

After a few days in Basid, I recruited my jeep driver to take me deeper into the Bartang Valley, to a hamlet known as Bardara. Similar to its neighboring villages, Bardara is perched atop a giant alluvial fan spilling down from precipitous peaks and spanning the width of the river canyon. As we puttered up to the edge of the alluvium on switchbacks, over 40 villagers amassed to usher me through their maze of turf pathways, gurgling water canals, and bursting apple blossoms. It was simply the loveliest place I had ever visited. But it was soon apparent that the warm nature of Bardara’s residents easily surpassed the appeal of its physical beauty. To accept each household’s invitation for tea would have consumed weeks; at last, I embraced their hospitality, staying five days with one family, and having tea with many others.

My first morning in Bardara, the children eagerly gathered to show me the village sights. Bardara is an unlikely place for thousand-year-old juniper trees, although it claims three of them, in linear alignment and perfectly equidistant. Legend has it that Nasir Khusraw, the Persian poet and missionary who established Ismailism in greater Badakhshan, planted the trees. The middle tree contains the village shrine, Farmon, memorializing a religious communication to Bardara from Aga Khan III, the late grandfather of the current imam. Farmon also boasts an impressive collection of spiraling Marco Polo sheep horns, whose significance in Pamiri tradition as symbols of purity concern Aryan and Zoroastrian philosophy, pre-dating Islam in the region.

Later, we set out on foot for Bardara’s alpine summer pasture, which provides seasonal grazing for livestock, although it’s too lofty and temperamental a place to support fruit trees. A half dozen families reside in this final node of civilization, nestled at the foot of a series of peaks reaching nearly 20,000 feet. Life here occurs on the margin, and they utilize nature’s resources to the brink, including a hydro-powered wheat mill and small hydroelectric generator to power a few light bulbs. The Pamiris have finely tuned their self-reliance, particularly since the abrupt cessation of communist sponsorship in 1991. Many here recollect the Soviet era with a sense of yearning. Visiting in the summer, it’s easy to overlook the rigors of a long winter in the heart of the Pamir Range.

My last night in Bardara, we slaughtered a goat to celebrate newfound friendship. Sleep escaped me that night as I reflected on my growing affection for the people of the Bartang Valley. The initial perception I recalled having of this inhospitable backwater of Central Asia only weeks before now seemed foreign. Here I acquainted a people, a religion, a story completely unknown to me. Here I experienced a way of life remarkably unaffected by the world from which I had come. Here I found a landscape so serene, it was to imprint my memory forever.

Here in the Pamir Range, I felt at home.