The view of the San Francisco skyline humbled me each and every morning as I emerged from the Robin Williams Tunnel (formerly the Waldo Tunnel), heading south on Route 1.

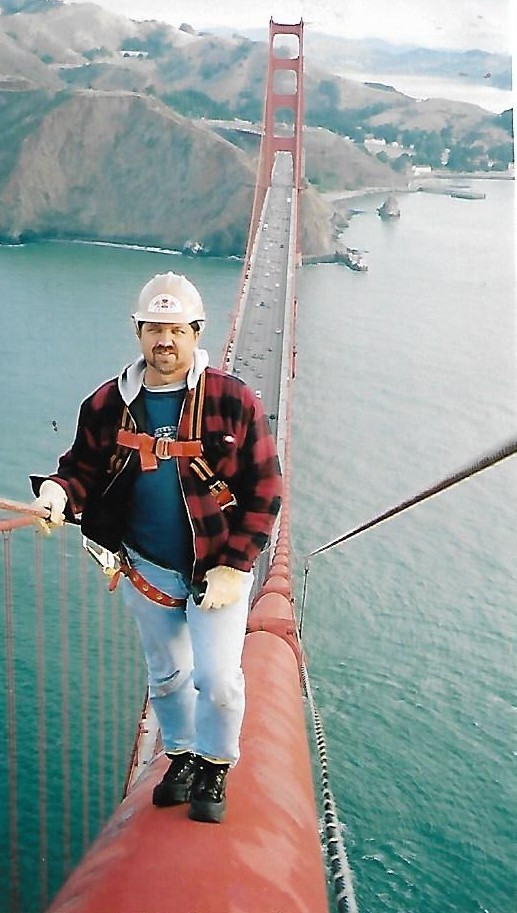

I always dreamed of being a painter on the Golden Gate Bridge. What an honor to be responsible for keeping such a tremendous achievement of both design and construction safe in my hands! Constant maintenance from a permanent paint crew is required to dress this architectural treasure with a coat of International Orange, protecting it from the natural erosions of wind and fog, as well as the constant exposure of the steel to the salty air. It is a glorious job for any painter, and I am proud to have risked life and limb to do my part to keep the Bridge standing forever.

On my first day as a Golden Gate Bridge painter, the paint department superintendent, Rocky, took me onto the bridge in his paint scooter. He told me that the east sidewalk, which faces the bay was open to the public, both pedestrians and bicyclists. The west sidewalk, facing the ocean, was exclusive to bridge workers during the weekdays, off limits to tourists. We took to the east sidewalk first, and Rocky emphasized that dealing with tourists was an important part of our job. He insisted that I be courteous, take time to answer their questions, and try to make their visit to the Bridge as pleasurable as possible.

I always enjoyed the privilege of interacting with so many tourists and visitors through the years. At times, I felt like one who had been hired to wear a Mickey Mouse costume at Disneyland, posing for selfies, pointing the way to the restrooms, and having kids stomp your feet. Being involved in a visitor’s bridge experience became a simple means of sustaining my love for the bridge, helping to make my job more than “just a job”.

A variety of questions concerning my years at the bridge are asked, but often the same ones come up ad nauseam, making the answers quite repetitious:

“Yes, that is Alcatraz Prison; the color of the bridge is called International Orange; an elevator in each tower goes to the top; no, we do not paint the bridge from one end to the other, then start again. Answers such as these become part of our daily routine as bridge painters.”

Another not-so-trivial subject matter often inquired upon by visitors to the Bridge, and still asked today when people find out what I did for a living, “What do you know about suicide jumpers?”

No doubt, suicide jumpers come to mind when one thinks of the Golden Gate Bridge. Questions concerning this subject may be asked out of harmless morbid curiosity; or possibly fueled by misconception of urban myths, such as those leading people to believe that suicide jumps, like earthquakes, happen here everyday, which of course, they do not.

Thousands of tourists from all over the planet flock to the Golden Gate Bridge every day, but it is no secret that the Bridge’s intrigue, mystique, and popularity also attract another element; those looking to end their lives in a romanticized manner by jumping off this famous landmark.

This article is not intended to analyze the psychological reasons of why a person leaps from the bridge, because I actually know little about the subject. If the Bridge knows why people jump, it is unable to tell its secrets, so I will try my best to share with you all I have witnessed concerning jumpers, and along the way, try to answer some of the questions I have been asked about suicide jumps at the Golden Gate Bridge.

As of 2019, an estimated 1,700 people have jumped from the Golden Gate Bridge, with only twenty-five known survivors. The number of deaths is considerably higher if counting those who jumped at night that went unrecorded. During the last few decades, an average of nearly thirty people a year have jumped off the bridge.

Profiles of jumpers were not kept in the early years of the bridge, but using the information we do have from past jumps and the accurate records kept now, we have an idea of some trends and characteristics of the jumpers. Jumpers are almost exclusively from the Bay Area, with the average age being forty-one years old. Occupations of the jumpers have varied over the years. Professors and students usually lead the list, with suicide jumps by software engineers recently on the rise. About 80% of the jumpers are white, and 56% are not married.

Suicide jumps are obviously random. Sometimes there can be three or four jumps in a week, and other times, several months may go by without a reported jump. One fact, not so random, is that male jumps far outnumber female jumps (three males to each female), but females do unfortunately jump, and when this does happen, it makes a permanent impression, much different than seeing a male jump.

WOMEN JUMP TOO

Minimal cloud cover accompanied with the fog having lifted hours earlier made for a rare sunny afternoon at the bridge. My partner Mike and I had been assigned the task of attending to the sandblast pots at midspan, on the west sidewalk. Other crew members sandblasted rust off the underside of the road deck and floor beams directly below us.

As point men for the operation, our main duties included keeping the sandblast pots full of sand and coordinating with the crew below using bridge radios. Having shut the operation down, we waited for the rest of our crew to climb up from below. Leaning on the outer safety rail, I took a moment to enjoy the gorgeous day, but my bliss was interrupted while noticing unusual activity across the roadway, about a hundred yards from where we stood.

Number one lane northbound, the lane closest to the sidewalk had been closed off by bridge patrol. A patrol vehicle had pulled right up behind a vehicle that appeared to be stalled. This was not a rare sight on the bridge, but curiosity had gotten the best of us, so Mike and I started walking down the opposite sidewalk to get a better view.

We noticed the vehicle parked a bit irregular, with the driver’s side door still open. The vehicle looked abandoned. A commotion began on the east sidewalk. I saw what seemed to be a small woman standing with her back against the outer guardrail. She appeared to be in an agitated state.

Curious to know what was happening, I turned my bridge radio on, listening as bridge security assessed the situation. The report said the woman stopped her vehicle in the first lane, jumped out, ran around the car, crawled through the safety barrier that separates the roadway from the sidewalk, then ran across the sidewalk to the outer rail where she appeared to be in some sort of a stand-off with two bridge security officers.

I saw the two officers cautiously approach the nervous woman, who now had one of her hands on the guardrail, the other at her side. The officers were careful to keep a safe distance and appeared to be pleading with her. Why not just pounce on her, and grab her before she had a chance to jump over the rail? The answer came over the bridge radio.

According to the report, she held several hypodermic needles in her hand, and began acting violently towards the officers. I could see the woman, needles in hand, wielding them like a knife, hacking and slashing them vigorously. She had remarkable aggressiveness for someone so small. Each time the officers moved close to her, she poked and jabbed them away. She obviously did not want anyone near her.

Then, as if having no doubts or second thoughts in accomplishing what she had come to the bridge to do, she rolled her petite frame up and over the guardrail so quickly that the lunging officers had no chance of grabbing her. She left our view. She had jumped. Mike and I gasped in horror. We knew the only thing beyond the rail, were a three foot wide steel chord, and then a 200 feet fall to the waters below. Surely, she was gone.

Both officers quickly approached the rail and looked over. Then, a frantic report came over our radio saying that the woman actually still held on to the outer edge of the chord. We looked at each other with amazed approval. No sooner had we gotten our hopes up, that we saw the officers twist their bodies in frustration. We knew at that moment, the woman could not hold on any longer, or she had let go on her own, but either way she had obviously fallen. By the time she hit the water, the Coast Guard had time to position themselves below her, but soon after, we heard the radio describing it as a recovery, not a rescue. Sadness overcame me. The incident happened so fast it is impossible to explain the emotional overload and feeling of futility to witness something like this and be utterly helpless to assist.

I feel sorrow for the two bridge patrol officers and what they must have to live with, always wondering if they should have just sacrificed themselves, and taken the stab from the needles filled with “who knows what”, to save a woman who wanted more than anything to die on this day.

OUR VOYEURISTIC SOCIETY

Eric Steel’s documentary film, The Bridge came out in 2006. The project focused on suspicious people who might be considering jumping off the bridge, and to actually record their jump on film. Steel and his crew set up stationary surveillance cameras in various locations, filming the Golden Gate Bridge day and night. Telephoto and wide-angle cameras captured 10,000 hours of footage recording 23 suicides off the Bridge in 2004.

The project became a viral sensation for awhile, but legal issues prompted its removal from the Internet shortly after its release. Steel had misled bridge officials about his intentions, stating on his permit that he intended “to capture the powerful, spectacular intersection of monument and nature, that takes place every day at the Golden Gate Bridge.” Bridge officials cited an increase in suicide attempts as the documentary began appearing at film festivals and attracting publicity, and argued the film an “invasion of privacy”.

The film had mixed reviews. Critics called it nothing more than morbid and unethical voyeurism. The New York Times called it “gripping viewing but you feel like a voyeur of somebody else’s pain.” Andrew Pulver of The Guardian went as far as saying it “could be the most morally loathsome film ever made.”

Steel defended his film as an anti-suicide project. He stated that most of his film focused on heartfelt interviews with loved ones the suicide jumper left behind. Steel argued that he may have prevented at least six suicides when his film crew pointed out suspicious characters to bridge security officers, who removed the possible jumpers from the Bridge. He also has on film a woman’s life being saved when a passerby pulled her back over the rail.

Of course, this is not where controversy lies. We are a voyeuristic society by nature. We desire to be indulged and shocked by “reality TV” and “fake news”. The public interest and curiosity in Steel’s film did not come from the lives that were saved, but from those that were lost. One of the 23 suicide jumps in 2004 I remember all too well. I experienced it live from a different angle, and have a much different perspective than when I saw it on film.

While walking along the bridge sidewalks, the gentle morning mist wraps you in a blanket of fog, teasing your senses with a slight satisfying chill. The fog, accompanied by the eerie call of the bridge foghorns below can almost give the impression that this mass of concrete and steel is perhaps a living entity. Energy flows through the muted steel, and between foghorn blasts, a hush fills the emptiness like a voice waiting to speak.

Weather conditions change at a moment’s notice on the Bridge, and its tempestuous tantrums can command your attention in other ways. Continuous gusts of bitterly cold wind can wail on you relentlessly, one after the other, tearing through your body. Grabbing hold of you and not letting go, the Bridge wants you to know there is power behind the beauty.

The Bridge has given me views of the San Francisco Bay Area that are breathtaking. I have spent evenings atop the South Tower staring out for hours at unimaginable sights, such as an evening view of the City lights, or the rising moon breaking out of the clouds at midnight over the ocean. Experiences such as these gave me a chilly delight that I could never tire of, nor forget. Looking back, I was lucky bridge management did not know they actually paid me to do a job I no doubt would have done for nothing.

WHEN A JUMPER HITS THE WATER

If you work at the Golden Gate Bridge long enough you have probably seen at least one person go over the outer rail, heard a splash from someone hitting the water, or seen the body of an unfortunate jumper floating in the bay; but to witness an entire jump is a rare occurrence. Something like being at the wrong place at the wrong time.

It was May of 2004, a sunny morning at the bridge. Robin and I had been tasked with painting below the bridge atop the west end of the South Tower Pier. The piers are the massive concrete bases that support the legs of both the north and south towers. The piers extend perpendicular away from the bridge, outward across the water. The tops of the piers sit approximately 44 feet above sea level. Surrounding the South Tower Pier is an oval shaped concrete fender that acts as both a wave break and a barrier to keep ships from colliding with the tower. Between the pier and this outer fender is a moat filled with seawater that flows freely in and out.

Working on the pier always gave me a unique perspective of the Bridge, as if being on my own little concrete island in the middle of the bay, blessed with incredible views that most never see of San Francisco, Alcatraz, the East Bay, Fort Point, and Marin County. I enjoyed these sights from the pier for years.

On this particular morning, the unforgettable sight came from above. A call came over our portable bridge radio that a distressed man was pacing on the east sidewalk, between the South Tower and midspan. He had been talking with bridge authorities for two hours on his cell phone, contemplating a jump off the bridge, and threatened to jump if anyone approached him. Our position on the pier enabled us to have a clear view of the east sidewalk’s outer rail. The rail stood about 200 feet above us, and about 240 feet above the water. Unable to see the man on the sidewalk, Robin and I returned to our project on the pier, hoping for a resolution to the negotiation standoff above.

Then suddenly Robin grabbed my arm, diverting my attention to a man with long hair sitting on the outer rail about 100 yards north of the South Tower, towards midspan. From my vantage point, he appeared to look calm, perched on the rail with his back to us, casually talking on his cell phone. After watching him for several minutes, I doubted his intention to jump, having had plenty of time to contemplate his inevitable fate if he jumped.

I figured wrong! I looked away for just a moment, then heard Robin yell, “Oh s___,

He’s jumping!” I immediately looked up to see a man falling feet first with his back to us and his arms stretched out above his head.

One…Man falling.

The man did not scream as he plummeted to the water, but I remember hearing his clothes flapping loudly.

Two…Man still falling.

His shirt and undershirt began to peel off his body. They were wrapped up over his head, ready to fly off his wrists as he neared the water.

Three…Man still falling.

Even though the man traveled downward extremely fast, the four seconds it took him to reach the water seemed so much longer. I can not imagine how long the four seconds must seem to the jumper.

Four…Man hits water.

The man hit the water causing a huge splash, followed by the most defining moment of the jump, the sound.

For the first few months I worked at the Bridge, I would look down from the sidewalk at the 240-250 feet drop, and wonder why more people did not survive the jump. It did not look like a fatal distance from above, especially with clam waters on a pleasant day. Watching this man collide with the water forever ended all such notions for me.

I was shocked by the splash and the sound that followed, which I can only liken to a shotgun blast. My body cringed from this sick sound, an unforgettable sound, a sound that told me this man’s body had been broken in so many ways. Undoubtedly, this man did not survive. I closed my eyes knowing, at that exact second, I had witnessed a death.

Being at an elevated position atop the pier, I could see the victim less than a hundred yards away, drifting along in a swift current. He remained submerged three to four feet below the water’s surface, surrounded by a ring of blood. A sobering sight.

Shortly thereafter, a smoking kettle that signifies the location of a jump came crashing down into the water near the body. Alerted to the possibility of a jump, the US Coast Guard wasted no time getting to the body. Unfortunately, no rescue or resuscitation would be needed upon their arrival, only the retrieval of a broken body.

Mixed emotions overwhelmed me, at once feeling astonished, humbled, and sad. My misconception that a jump from the sidewalk can be survived, ended in an instant. Bridge workers later impressed upon me the rarity of witnessing an entire jump as I had, but I did not feel privileged. Although I had never met Gene Sprague, I feel sorrow even today for having witnessed his passing.

THE DANGEROUS OUTER RAIL

The east sidewalk is the setting for almost every jump. The sidewalk is a ten feet wide concrete walkway that runs the length of the bridge, taking gradual turns around each tower. A safety barrier, constructed in 2002, protects pedestrians from the roadway, separating the sidewalk from “lane one”. About every hundred yards, metal latched emergency gates have been installed for bridge patrol and tow service to access the sidewalk from the roadway.

The sidewalk’s outer steel guardrail is slightly over four feet tall and runs the length of the bridge. Rumor has it the low rail height can be attributed to bridge designer Joseph Strauss being only five feet tall. Beyond the outer rail, three feet below the outside edge of the sidewalk, is a three feet wide steel box chord, which is the only thing between the outer rail and a 240 feet fall to the waters below. Due to constant fog and moisture in the air, the top of the chord is wet nearly all the time and can be extremely slick. Very dangerous conditions for those of us who walk on steel every day, let alone a nervous person climbing down onto it for the first time.

A victim caught on surveillance video learned a tragic lesson about the dangers of going over the outer rail. It is late evening, and a middle-aged man stands alone on the sidewalk near a light pole, not another soul in sight. Fog blanketed the bridge on this dark drizzly night. The heavy mist gave the sidewalk lighting an eerie faded glow, just enough light to help guide him over the guardrail. Awkwardly he climbs over the rail and now stands on the chord ready to jump.

Suddenly, he appears to be having second thoughts about his decision. He does not want to jump. He is scared and disoriented, but not ready to end his life. He gets up his nerve to climb back over the rail to safety.

He reaches for the handrail but comes up considerably short. Due to the drop from the sidewalk to the chord, the top handrail is now over seven feet above him. The chord glistens with moisture, and must be very slick. The man can only reach the bottom of the guardrail, which he now tightly holds on to, searching for a foothold that will allow him to hoist himself back over the rail. His foot slips from the beam, and his grip fails him. Falling back down to the wet chord, he slips off the chord, out of sight from the video camera and ultimately gone forever, falling to his death. He learned the hard way how slick and dangerous the outer chord can be, and will never get his second chance at life.

SURVIVOR REGRETS

A small percent of jumpers are rescued and live, but it takes “more than just luck” to survive a jump from the Golden Gate Bridge. Accounts given from jump survivors all point towards sincere regret setting in immediately after they jump. It can be assumed that most of the hundreds of jumpers who were not lucky enough to survive, had similar regrets.

Suicide can be attempted many different ways. Most methods to take your own life are fallible. Suicide by jumping off the Golden Gate Bridge constitutes a good chance of success, a 98% success rate to be exact. In four seconds, it is all over. During the four seconds fall, the body will travel the 240-250 feet at 75-80 mph, ending with a bone shattering impact of 15,000 pounds per square inch.

This type of fall will destroy a body and most times cause an instant death. For those that actually survive the fall, their unconscious body will most likely drown from asphyxiation, or breathing in too much salt water in the swift moving 350 feet deep channel. Those who remain conscious may succumb to extensive internal bleeding while trying to stay afloat. They may also die of shock, and if not rescued quickly can die of hypothermia in the frigid waters.

On September 4th, 2000, nineteen year old Kevin Hines took a 240 foot headfirst dive off the bridge. During the jump, Hines decided he wanted to live, so he rotated his body to hit the water feet first. He hit the water in a sitting position, taking impact in his legs and through his back. The US Coast Guard rescued Hines immediately. He had suffered serious spinal damage as three of his vertebrae were shattered lacerating his lower organs, but he was alive.

Hines’ regret is obvious in this heartfelt post-jump statement, “There was a millisecond of free fall. In that instant, I thought, what have I just done? I don’t want to die. God please save me.” Hines has since regained full mobility. He is a mental health advocate in the prevention of bridge suicides and wrote a book about his suicide attempt called Cracked, Not Broken.

I remember another jumper and his amazing feat of survival. On March 10, 2011, a report came over our bridge radio that a man held onto the outer chord after climbing over the rail at the south end of the bridge between the South Tower and the South Anchor Block. (Later we found out the jumper to be Luke Vilagomez, a seventeen year old from Windsor, California on a field trip with his high school class.)

I leaned over the rail and saw the teen dangling over an area where local surfing enthusiasts sometimes spend their lunch hour catching a few waves. Vilagomez eventually let go, falling into the water, landing near a group of these surfers. One of the surfers, fifty-five year old Frederic Lecoutier, who had an extensive background, helped the injured teen to shore. Lecoutier resuscitated Vilagomez, thus saving his life. Vilagomez broke his coccyx and punctured a lung, but survived. The teen later claimed he jumped for “fun” and not suicide, but whatever the reason, this serves as a good example to what I meant by a jumper sometimes needing to be “more than just lucky” to survive a jump.

Next, is the unusual case of Paul Aladdin Alarab from Kensington, in the East Bay, who miraculously survived a fall from the bridge in 1988. As an act of protest to what he believed to be the mistreatment of the elderly and handicapped, Alarab lowered himself into a garbage can that hung from a 60 feet rope off the bridge. He lost his grip on the rope and fell. He had three broken ribs and both lungs collapsed but he survived. Alarab told the San Francisco Chronicle, “it seemed like the fall lasted forever. I was praying for God to give me another chance, I was also wondering about how I would hit, because that is what determines if you will live or die.” This incident was considered an accident, not a suicide.

Fifteen years later, Alarab again found himself in a compromising situation at the Bridge. On March 19, 2003, the forty-four year old Alarab, protesting the U.S. invasion of Iraq, tied one end of a rope around his arms, then climbed over the rail at midspan, dangling below the outer chord. Alarab read a statement he had written denouncing the war while law enforcement tried to talk him back over the railing. After finishing the statement, he let go of the rope and fell to the waters below. This time he did not survive. Investigators ruled it a suicide this time. I guess beating the odds of surviving a jump from the Golden Gate Bridge, obviously was not enough for Alarab.

TALKED OUT OF JUMPING

Various methods have been tried to reduce the number of suicides. Suicide hotline telephones are installed throughout the bridge, and staff regularly patrol the bridge in carts or on bicycles, looking for people who appear to be planning to jump. In addition to Golden Gate Bridge patrol, law enforcement and emergency medical personnel, bridge management take pride in training employees from other departments in suicide prevention.

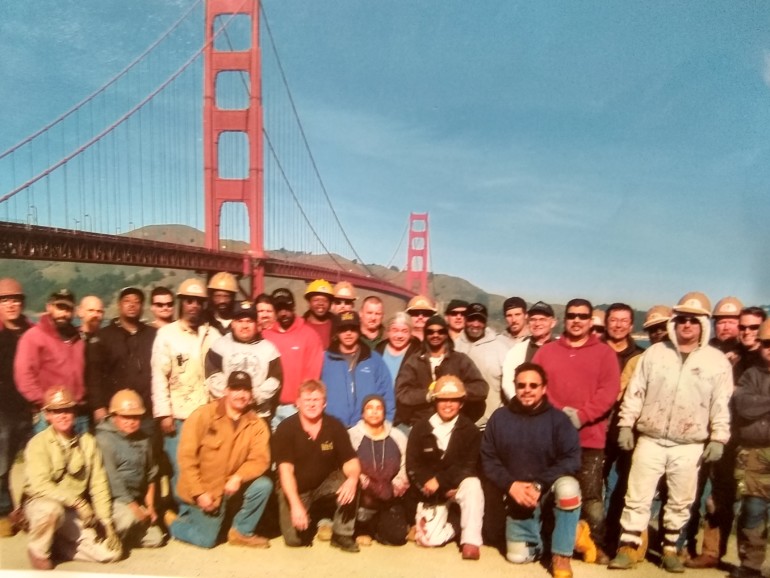

Golden Gate Bridge ironworkers and painters volunteer their time to prevent suicides, and receive training on the various signs to look for concerning someone in crisis, such as ways to engage people walking alone on the bridge, or safety protocol when approaching a suspicious person who requires police intervention. These tactics have helped convince many people not to take their own lives.

California Highway Patrol patrolman Kevin Briggs is credited with saving hundreds of lives of would-be-jumpers by talking them out of jumping. The CHP estimates that with the help of cameras and volunteers, at least 80-90% of people intending to jump are prevented from doing so, but sometimes all the training in the world is not enough, and just being yourself and lending an ear to someone in distress can be the remedy.

A woman had climbed over the guardrail and stood upon the outer chord below. Scared and trembling, she clung tightly to the bridge support cables that ran up through the chord, threatening to let go if anyone tried to grab her.

Alfredo, a bridge painter working nearby, calmly approached the frightened young lady. He sat next to the troubled woman for over and hour, and through dialogue full of heartfelt concern and patience, Alfredo eventually talked this desperate person out of jumping and then helped her back over the rail to safety.

The crowd that had gathered around the incident, including myself, began cheering as Alfredo helped the woman into the bridge patrol scooter that would take her off the bridge…alive. For this woman, the odds of remaining alive are good. A study started in 1978, of people stopped from jumping off the Golden Gate Bridge, found that 94% were still alive more than 26 years later. It was a glorious achievement, and for his act of caring, Alfredo was awarded Bridge District Employee of the Year by the Golden Gate Bridge Board of Directors. There is now one more person in this world with a second chance at a happy life thanks to Alfredo.

U.S. COAST GUARD

The U.S. Coast Guard is on constant alert for jumpers, and when a person is seen jumping from the sidewalk, U.S. Coast Guard will be first responder to the scene. U.S. Coast Guard Station Golden Gate is in Sausalito at Fort Baker on Horseshoe Bay located under the bridge near the north end. The station has two 47 feet long motor lifeboats. When someone jumps from the Golden Gate Bridge, one of these two boats can get to the scene in four to five minutes with sailors who retrieve the jumper and perform lifesaving measures.

Spotting a body can be difficult to see at eye level from a Coast Guard rescue vessel. As soon as a jump is confirmed, bridge patrol will drive to where the jump occurred, exit onto the sidewalk through the access gate, and immediately drop a smoke flare (which is basically a smoking kettle the size of a basketball) straight down into the water, from the spot the jump was made.

The jumper’s body will sometimes be submerged several feet below the surface, and start drifting even before Coast Guard can get to the scene. The smoking flare will drift the same route as the body whether the tide is ebbing or flowing inward. This way, the Coast Guard can follow the rising smoke to locate the body quickly. This will give the Coast Guard a better chance at a rescue.

Coast Guard is ready to respond quickly to revive a drowning victim, administer CPR to an injured survivor, get a potential survivor out of the water before hypothermia can set in, unfortunately most cases end with the grim task of locating and removing a lifeless body from the water.

REACTIONS TO PEOPLE WHO JUMP

Not all bridge employees had compassion for suicide jumpers. Some of these people rationalized that if a person wants to jump, let them. Others were not interested either way. Then there were those who actually found a way to capitalize and create amusement from another’s tragedy.

The Golden Gate Bridge, like work places all across America, had many types of gambling by its employees. Poker games, dominoes, football pools, parley cards, basically, any type of gambling that could exist, did. Management frowned on gambling in the workplace, but good luck trying to eliminate it.

An enterprising employee decided to take workplace gambling to its lowest possible level, when one day a “jumper pool” surfaced. The format was a monthly calendar, with blank squares for each day of the month. The participant paid for a square, then chose any day on this calendar, and signed his name, initials, or alias. Simple objective, a suicide occurring on the day he chose, and he wins all the money built up since the day of the last jump. If there are no jumps during that month, the pot rolls over to the next month.

I saw this pool as just a bad joke, or a novelty that would soon go away. It did not just go away, in fact the first month’s sheet filled up so fast that another pool for the month was added. A small percentage of employees participated in the pool and most others thought it to be irresponsible, and in bad taste. The players were not necessarily evil people, they were just among those who had no compassion for jumpers, or those with a serious gambling addiction.

Not much mystery to the identity of those in the pool. They were usually the ones running in to bridge security first thing in the morning to ask if there were any jumpers the day before. I could not avoid the thought that every time a person jumped, a fellow worker just made some money. It was hard imagining someone actually hoping a person jumps off the bridge on a particular day, just to make a few dollars, but I guess we are all different people.

This pool discreetly flourished for a few months, but good judgment eventually won out, and interest wavered. Bridge management learned of the pool’s existence. Horrified, they immediately laid down a zero-tolerance rule. Anyone involved in these games would be unconditionally terminated. Management also punished the rest of us by banning all types of gambling and wagering. Collateral damage can be a motivational force, and the rest of the department rose up against the abhorrent pool and put a swift end to it. Eventually the football pools and card games resurfaced, but hopefully the “jumper pool” will stay gone forever.

FIRST JUMPER AND OTHER STORIES

Harold B. Wobber, a forty-seven year old World War I veteran, walked the pedestrian sidewalk in August of 1937, just a few months after the Bridge was opened. Another man strolled alongside Wobber, when suddenly Wobber took off his coat and vest, threw it to the man and said, “This is where I get off. I’m going to jump.” The other man grabbed Wobber, but Wobber broke free and threw himself over the rail. Wobber officially became the first person to jump off the Golden Gate Bridge.

Since Wobber’s jump over eighty years ago, suicide jumpers have chose many different ways to end their lives. Many park in the lots at either end of the bridge and walk to the spot they choose to jump. There are also impulse suicides, involving those who just stop their car, run to the rail and go up and over. Still, others go down onto the outer chord below the guardrail, and just stand there contemplating the reasons that brought them to this point, taking in the last few breaths they will ever take.

Many jumpers have left suicide notes. Apologies, health issues, and of course, references to sour relationships head the list of fateful subjects. Sometimes notes can be heart wrenching like this tragic note left by a young premed student from UCLA in 1954, who followed his father off the Bridge just four days after his father had committed suicide. The note read, “I am sorry…I want to keep Dad company.”

Kyle Gamboa, a high school student from Fair Oaks near Sacramento, skipped school one day in September 2013, to jump off the Bridge. The New York Times reported that he had repeatedly watched the trailer for Eric Steel’s documentary The Bridge. He yelled “yahoo” as he leaped to his death. His suicide note read, “I’m happy. I thought this was a good place to end.”

Disturbing tales and accounts have circulated around the Bridge for decades about those who desire more than just an end to their lives, they want to make a statement as well. Once in awhile a selfish man, not wanting to leave anything behind, will jump with his life savings in his pocket. There are those who committed criminal acts, taking computers or other incriminating evidence over the side with them. In one case, a seventy years old man jumped after murdering his wife.

One tragic account involved a couple making a lover’s leap together. Some sort of a pact, over the rail hand in hand, four last seconds together. Jumpers have taken their pets with them. Most of the times they hold onto their pets when they jump, but I remember one sad instance where I watched a man toss a helpless dog over, before jumping himself.

Pets are not the only ones who go over the rail unexpectedly. Terrible incidents have taken place where jumpers, in their moment of instantaneous desperation, take innocent people over the rail with them. A man got into an argument with his girlfriend near the South Tower. He became so upset that he forcefully shoved the woman up and over the guardrail, and then followed her over the side. Both died, but the girlfriend unfortunately did not get to choose where she landed, and missed the water, hitting the concrete fender surrounding the pier.

On January 28, 1993, Steven Page killed his wife Nancy in their Fremont house with a 12-gauge shotgun. Page the drove his three years old daughter Kellie to the Golden Gate Bridge. Highway patrolmen approached Page who looked suspicious carrying his child on the bridge sidewalk, causing Page to immediately throw his daughter over the rail and then he jumped himself. A note Page had earlier left, telling how sorry he was about the murders he would commit, left no doubt the terrible incident was premeditated.

Until the shocking Kellie Page murder in 1993, the youngest death was five years old Marilyn Demont in 1945. With the child standing on the chord just outside the bridge railing, her father, August Demont, a thirty-seven years old elevator installer, commanded her to jump. After Marilyn jumped, her father followed her over. A chilling note later found in his car read, “I and my daughter have committed suicide.”

Fellow painters told me of an incident they witnessed a couple years before I came to the work at the bridge. A man stood next to a random young girl he did not know. He suddenly grabbed the girl, intending to jump off the bridge with her in his arms. Luckily, several people in the vicinity wrestled the girl from his grip, saving her from a horrific fate. The man jumped alone.

It is hard to grasp one’s state of mind as their own demise is not enough, that in a moment of senseless desperation, they choose to add the murder of an innocent victim to their final act.

PHYSICALLY STOPPED FROM JUMPING

Management takes great concern that we go home alive every day. As high steel painters, we spend many hours training to work safely. A required policy is that we always work in pairs, insuring the safety of our partner, as well as our own. We can never know when a life threatening situation involving a fellow worker will arise, but must be prepared when it does. As employees, we do not always get along with one another, but this is okay, because when the opportunity calls we definitely have each others back, as this next account illustrates:

Driving southbound towards San Francisco in the far lane next to the west sidewalk, a man abruptly stopped his car, jumped out and climbed onto the west sidewalk through the safety barrier. As pointed out before, the west sidewalk is for bridge worker access only, and off limits to tourists, but concern for such trivial restrictions seemed meaningless to this man.

I happened to be driving my paint scooter down the east sidewalk when I saw this man stop his car and run for the west sidewalk. A large commotion began, highlighted by skidding tires and honking horns as cars swerved to miss the abandoned vehicle. This man, like the woman jumper mentioned earlier, had his mind made up that he wanted over the rail, into the water, and out of his life.

Things were happening so quickly, no way bridge security would get to this man before he could jump. The man entered the sidewalk, and I noticed him heading towards one of our paint scooters parked near the South Tower. Two painters sat in the parked scooter, Brian in the cab, and Mar in the back.

The jumper headed for the outer rail at the South Tower. Spotting the man, Mar jumped out of the scooter and got into position to intercept the jumper before he could get to the rail. Just a few steps away from Mar, the man surprised us all when he took his car keys that he held in his hand, and threw them as hard as he could into Mar’s face. Mar grabbed his face in pain. The chaos did not stop here. Instead of side-stepping the stunned painter and continuing with his jump, this tall well built man used all his heightened anxiety, and ran straight into Mar, slamming him hard into the outer rail. The larger man grabbed Mar’s right leg and began trying to force the shocked painter over the rail.

This all happened in a matter of seconds. I watched in amazement and horror, helpless on the other side of the roadway, seeing a co-worker struggling for his life against a madman. The man lifted Mar’s right leg even higher, causing Mar’s left leg to rise off the ground too. I remember thinking that Mar might actually be thrown over the rail.

Then out of nowhere, Brian came up behind the crazed man, grabbing him around the neck, causing the man to release Mar, who fell to the sidewalk. Brian wrestled the would-be-jumper to the ground, burying the man’s face in the sidewalk. The man still violently protested, but Brian’s strength kept the man pinned to the ground until more help arrived.

Witnessing this bizarre chain of events left me feeling as though I had witnessed a scene from an action movie. Brian saved his partner when the opportunity presented itself, and served as a good example as to why we work in pairs. An ever-thankful Mar made sure Brian did not have to worry about buying his own lunch for a long time after this. Brian’s quick reaction not only saved his partner’s life, but the life of the potential jumper as well. I will never know how this new chance at life will affect the saved jumper, but he will have to deal with being alive for awhile longer, and hopefully make the most of his new opportunity. Going home alive is our number one priority at the Bridge, and all three of these men were alive at the end of this day thanks to Brian.

SUICIDE PREVENTION PROTOCOL

The Bridge has an efficient Suicide Prevention Response Plan. The U.S. Coast Guard have been mentioned as first responders when a jumper hits the water, but other measures are in place to prevent a prospective jumper from getting that far.

First line of jump prevention is a trained bridge security team, capable of responding quickly to any type of suicide jumper threat. For urgent cases, bridge patrol vehicles teamed with bridge tow service can create a lane diversion or closure to quickly converge on a possible jumper to question them, or actually remove the suspected jumper from the bridge to a safer place to talk further with bridge officials. For questionable, less obvious suspects, who may only be contemplating a jump, bridge security has patrol scooters and officers on bicycles that can discreetly approach a suspected jumper, creating a subtle encounter.

Due to the Bridge’s status as an American icon, it is considered a possible target for a terrorist attack. Since 9/11, security on the Bridge has become a high priority. High tech security also adds a new dimension to suicide prevention. Bridge security is able to monitor the Bridge much more thoroughly due to dozens of security cameras that have been installed on or around the Bridge during the past decade. From a main security room, suspicious characters are now watched much more closely, not just potential terrorists, but also suicide suspects. Consequently, this has become beneficial to bridge security, giving it another weapon in its arsenal of suicide prevention.

Another effective aspect of the Suicide Prevention Plan is an early warning system, that occurs when there has been a report by a family member, or loved one that there may be a person heading to the Bridge intending to commit suicide. In these instances, bridge security sends out a message over the bridge radio that includes a general description of the person’s physical characteristics, what he or she may be wearing, even a possible vehicle the person may be driving to the Bridge. This way, if we as bridge workers, come into contact with the person, we can inform security.

The last type of suicide prevention uses a more “hands on approach”, involving primarily bridge ironworkers and painters, because we frequent the sidewalks all day. We carry bridge radios with us and have the authority to report any suspicious characters we encounter to the bridge security. Of course, we also have the option of approaching possible jumpers and talk with them to determine what their intentions might be. To judge whether a person may or may not be contemplating suicide is not always easy, and is a difficult call more often than not.

SUICIDE DETERRENT NET SYSTEM (SDNS)

Proponents for a suicide barrier have long suggested that the Golden Gate Bridge’s popular legend, coupled with its easy access and relatively low safety rail, make it a prime destination for those contemplating suicide. Anti-suicide barriers on the Eiffel Tower and Empire State Building have been successful at deterring jumpers. Anti-suicide and mental health activists have pressured bridge directors for decades to create some sort of suicide barrier for the Golden Gate Bridge.

Bridge officials are sympathetic to the grief that families of suicide victims endure. I have attended public Golden Gate Bridge and Transportation District Board Meetings witnessing victim’s family members questioning whether their loved ones would have committed suicide had they not been drawn to the Golden Gate Bridge’s easy access to a jump.

On October 10, 2008, the Golden Gate Bridge Board of Directors voted 15-1 to install a stainless steel net as a suicide deterrent at a cost initially estimated at 40-50 million dollars. In 2010, the board received five million dollars from the Metropolitan Transportation Commission (MTC) for a final design study of the barrier.

Funding for the overall project had still not been determined, causing concern that this lack of money would delay the project. Funds for the building of the barrier were unanimously approved by the board on June 27, 2014. The MTC, along with federal and state grants, bridge tolls, prop 63 monies, and donations from both individuals and foundations would contribute to the now estimated 76 million dollar price tag. Finally, construction could begin on the suicide netting to deter suicide jumps.

The community selected design was chosen for its proven effectiveness and its minimal aesthetic. The completed SDNS will consist of 385,000 square feet of marine grade stainless steel netting attached to 369 structural steel net supports placed twenty feet below the sidewalk and extending out twenty feet over the water. The metal support beams will be installed first and painted International Orange. The metal net and border cables will be installed and remain gray to blend in with the ocean water below.

Another major change will be required to successfully install the new SDNS system. For decades, painters and ironworkers have used combustion engine powered travelers to do maintenance work on the structure beneath the bridge. These motorized scaffolds (travelers) wrap on the sides of the bridge and pass along the underside. Due to the new SDNS, these travelers will need to be removed, and replaced with smaller electric units. New railings must be installed to allow the travelers to move along the side of the bridge.

“This is the largest suicide deterrent net installation in the world, especially in the country,” said Eva Bauer Farbush, the Bridge’s chief engineer. “It is a technically complex project that requires a lot of effort from all vendors of the project team that are involved in bringing this to completion.”

Fabrication of the steel netting began off-site in May 2017, and installation of the netting on-site began in August 2018. The netting had originally been set for completion in 2021, but now delays have extended the completion date to 2023, and ballooned the final cost to 211 million dollars.

The delay rests solely on the contractors responsible for the construction of the net. Shimmick Construction in joint venture with Danny’s Construction submitted the low bid and were awarded the contract, but with construction on the net barely commencing, AECOM purchased Shimmick. The distraction brought confusion and disorganization to the project.

A frustrated Golden Gate Bridge General Manager Denis Mulligan, describes what he believed to be the reasons behind the delay, “AECOM was slow to mobilize on the job site. They lagged in building temporary construction platforms beneath the span, and the company presented an optimistic timeline that didn’t pan out, underestimating the time needed to complete certain steps.”

The delay also frustrates the backers of the suicide barrier because twenty-six people died by jumping from the bridge in 2019, so a two-year delay may cost another sixty lives. Two people who will not rest until the suicide net is completed are the parents of Kyle Gamboa, the high school student from Sacramento mentioned earlier. The pair have missed only one Bridge Board meeting in six years, and said they will continue coming to every single meeting until a new suicide net is completed.

UNPREDICTABLE BEHAVIORS

Nine million visitors from all over the world walk the Bridge every year. This makes for a lot of interesting people doing a lot of interesting things, and witnessing so many entertaining distractions on the east sidewalk made it nearly impossible to spot someone who might be contemplating a jump.

The infamous San Francisco afternoon wind can wreak havoc on those walking the bridge sidewalk. There is the poor soul whose hat blows off, followed by a quarter mile chase down the sidewalk each time reaching for the hat as it blows another ten feet away. Finally, he reaches the hat only to have it rise up and shoot into traffic, or the tourist who will discreetly toss their half drunk cup of coffee over the rail and have it swirl back up and drench the person next to them. Many times I have witnessed men repeatedly pulling the shirt down that keeps rising up from the wind to expose their portly vacation belly, or the girl frantically fighting to pull the dress back down that blew up over her head.

The Bridge’s unpredictable wind had a mind of its own and not always kind. Once I witnessed the wind do the unthinkable. A young lady fulfilled the last wish of a loved one by throwing their ashes off the bridge. The girl dumped a bag full of ashes over the outer rail, only to have the entire contents of the bag blow back up, covering herself and the dozen or so onlookers beside her with ash.

Bridge security had strict rules concerning conduct on the pedestrian sidewalk, but people can be just as unpredictable as the wind. Odd characters have always found ways onto the sidewalk to risk peril for attention. I witnessed a political protest during the running of the Olympic Torch across the Bridge in April 2008, when protesters ascended the South Tower from the sidewalk and unraveled a huge “Free Tibet” banner. I have also seen a man on a ten feet tall unicycle, a clown on stilts, and a woman doing back flips from one tower to the other.

I even had a man speed by me on a High Wheeler bike from the 1800s, ringing a little bell. The bike had a huge front wheel, a tiny rear wheel, and a seat above the front wheel sitting over five feet off the ground. Each turn of the pedals sent the big front wheel around once, so the bike traveled a long distance with a single turn of the wheel. The rider had no means of turning the bike, no control over his speed, and could not stop the bike if he had to. He just buzzed down the sidewalk loving all the attention he received, not caring that a single mishap or a big gust of wind could topple him over the outer rail to his death.

Luckily, most tourists on the sidewalk are not there for attention and keep a much lower profile. Many are amateur photographers, sporting poses with a backdrop of the bay, maybe a selfie glamour shot, silly pictures, or have a photo taken with a bridge worker. Others are pedaling their rental bikes up and down the sidewalk trying to stay upright as they weave their way through the sidewalk traffic. These are examples of actively busy tourists, obviously not a threat to jump.

Some tourists love to take in the whole bridge experience, stopping every few feet to catch all angles of the inspired view. They may look over the rail for hours at the beauty the Bridge has to offer, soaking up as much scenery as they can.

This is where good judgment on our part must come into play. Many jumpers waste no time jumping, as I mentioned in other jumps, but there are those who contemplate their intended leap for hours, whether through fear, doubt, second thoughts, or maybe just reflecting on their last precious moments on earth.

It can be hard to separate these types of pre-jump suspects from those just thoroughly enjoying the beautiful view. Confronted with this dilemma, I found it to be a good idea to politely approach the person, see what their intentions may be, and strike up a casual conversation to further evaluate the situation at hand. As you will see from my next encounter, even this can make for a difficult call.

APPROACHING A POTENTIAL JUMPER

One encounter I had with a potential jumper will never leave my thoughts. Despite having happened over a dozen years ago, I remember it as though it occurred yesterday.

It is getting near time for our A.M. break. We have spent the morning working in the cells that are located at the bottom of the South Tower. After our elevator ride up to roadway level, two painters and myself exit the tower onto the sidewalk. We head to our paint scooter that is parked beside the tower for our ride back to the painter’s break room.

This particular morning’s weather being foggy and overcast with a howling wind draws my attention to a young man at the outer rail looking extremely anxious, wearing only jeans and a beige short sleeved t-shirt. A cold wind, wet sidewalk, and moisture running down every inch of the steel is not the environment a somewhat disoriented sleeveless man should be hanging out in. This alone does not cause me too much concern because tourists are often caught underdressed due to misjudging the changing weather that San Francisco can offer up any time of year.

As far as I can see, the young man seems to be the only person on the entire east sidewalk. I ask my fellow workers to give me a couple minutes to talk with the man. As I get closer, he appears to be in his early twenties, unkempt, shivering from the cold, and nervous. He walks towards me as I approach him, and seems as though he wants to engage in conversation.

Noticing his soaking wet t-shirt, I say, “Looks like a real crappy day for sightseeing.”

“I’m not sightseeing,” he replies, “I’m waiting for my girlfriend to come by on her bike. She works in the city, and will be coming by here any minute.”

I look around seeing no signs of anybody coming, and doubt the possibility anyone would be out on a bicycle in this type of weather. “Dude you are gonna freeze,” I reply, “why don’t you wait for her at the gift center, café, or some place out of this rotten weather.”

Reaching into his pocket he pulls out a diamond ring, “When she comes by, I’m going to get down on one knee, hold this ring up, and propose to her right here at this tower.”

I have to admit that sounds romantic. Giving him a genuine nod of approval I smile and say, “That is really cool.”

I begin reasoning things in my head. Had he already proposed to her somewhere else and she refused leaving him depressed enough to contemplate a jump? Maybe no girl existed at all, and he is playing me so I will leave him alone? Perhaps she was real and actually going to come riding up at any moment, and this young man’s gesture will prove to be the most romantic moment in both of their lives? I have no idea what to believe.

What I do know is if I report this man to bridge security, his appearance and demeanor will definitely prompt them to come out here to question him, and perhaps they will be interrogating him at the moment the girl arrives on her bike, thus turning the romantic moment into an awkward embarrassing thing for them.

Once again, I scan the sidewalk just in case she is out there, still no sign of anyone coming through the gloomy darkness. Closing my eyes, I contemplate my options one last time, then put out my hand, grasp his tightly, and give the man a genuine smile, “Well good luck, I know she’ll say yes.”

“Thank you, thank you, I sure hope so,” he replies smiling.

I jump in the scooter where my co-workers are still waiting, and we head in for break. Who am I to stand in the way of true love! Break ends about thirty minutes later and we jump in the scooter to head back out to the South Tower. The weather seems much more pleasant upon our return to the tower. The fog that had clung to the bridge has lifted, dissipating in the warmth of the morning. I wonder how Mr. Romantic is doing, and actually smile at the thought of his success. After making the turn from the plaza onto the sidewalk, I see the northbound number one lane blocked off, and a bridge patrol car at the tower.

My hopes that I may be part of something special are immediately destroyed and replaced by feelings of intimate pain. A pit forms in my stomach, taking control and crying out for me to realize that some great misfortune is about to happen.

It is obvious there is a problem at the tower, but fear of what I may hear keeps me from turning the portable bridge radio on. The bridge patrol officer is on the sidewalk directly in front of the South Tower looking down over the outer rail. After parking the scooter, I look around but see no sign of anybody other than the officer. My bad feeling is getting worse. I head towards the officer.

“Jumper?” I ask in a somber tone.

“Yeah, a driver reported on their cell phone that they saw a man go over the rail about a half hour ago.” Answers the officer.

My heart sinks as I approach the rail and reluctantly guide my glance downward and see what I expect, but hoped not to see. There he is, floating face down in the moat, his beige t-shirt clinging to his lifeless body. It is the young man. I close my eyes and want to cry.

The officer can see I am upset, “Do you know this man?” he asks.

“No I didn’t, but I think I was the last one to talk to him,” then I ask, “was there any report of another person with him before or after the jump?”

“I haven’t heard,” the officer replied, “why, was there someone else here with him?”

“No, just curious, thanks,” I say.

I will never know whether he proposed and she denied him or if there was never any girl at all. It does not really matter anyway, because bottom line is I feel like I let a man die that day. Had I not favored curiosity over prudence, I could have prevented his death by reporting him and had him removed from the Bridge. I made the mistake of ignoring obvious signs for the sake of my faith that the “good” in this situation would prevail.

It took me awhile to come to grips with what happened that day. Anger at myself, frustration with him, sadness over the whole ordeal. I still think of him sometimes, and what I could have done differently. I have stopped condemning myself over the incident, and realize now that I never could have known for sure what went on in the young man’s head that day. No matter his reason for jumping, if there can be any upside to this tragic event, and I actually was the last person he had contact with, I gave the young man a real smile and a warm handshake before he left this world.

I am now retired from the Golden Gate Bridge paint department but people still ask me, “Wow, you worked on the Golden Gate Bridge, have you ever seen a person jump?”

I say, “Yes, and I pray nobody else ever has to see it again!”

How to Help

Here are some resources that can help if you, or someone you know, are struggling:

• @crisistextline – Text HOME to 741741 to connect with a counselor.

• National Alliance for Mental Illness (NAMI) Marin hotline – 415-444-0480