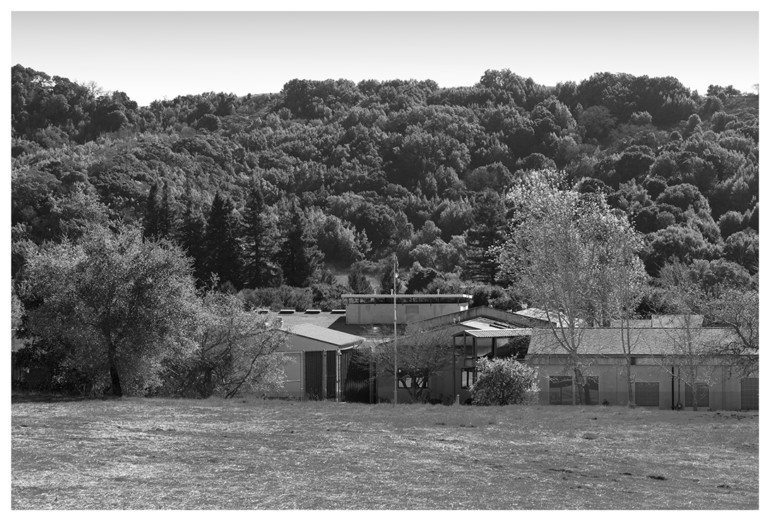

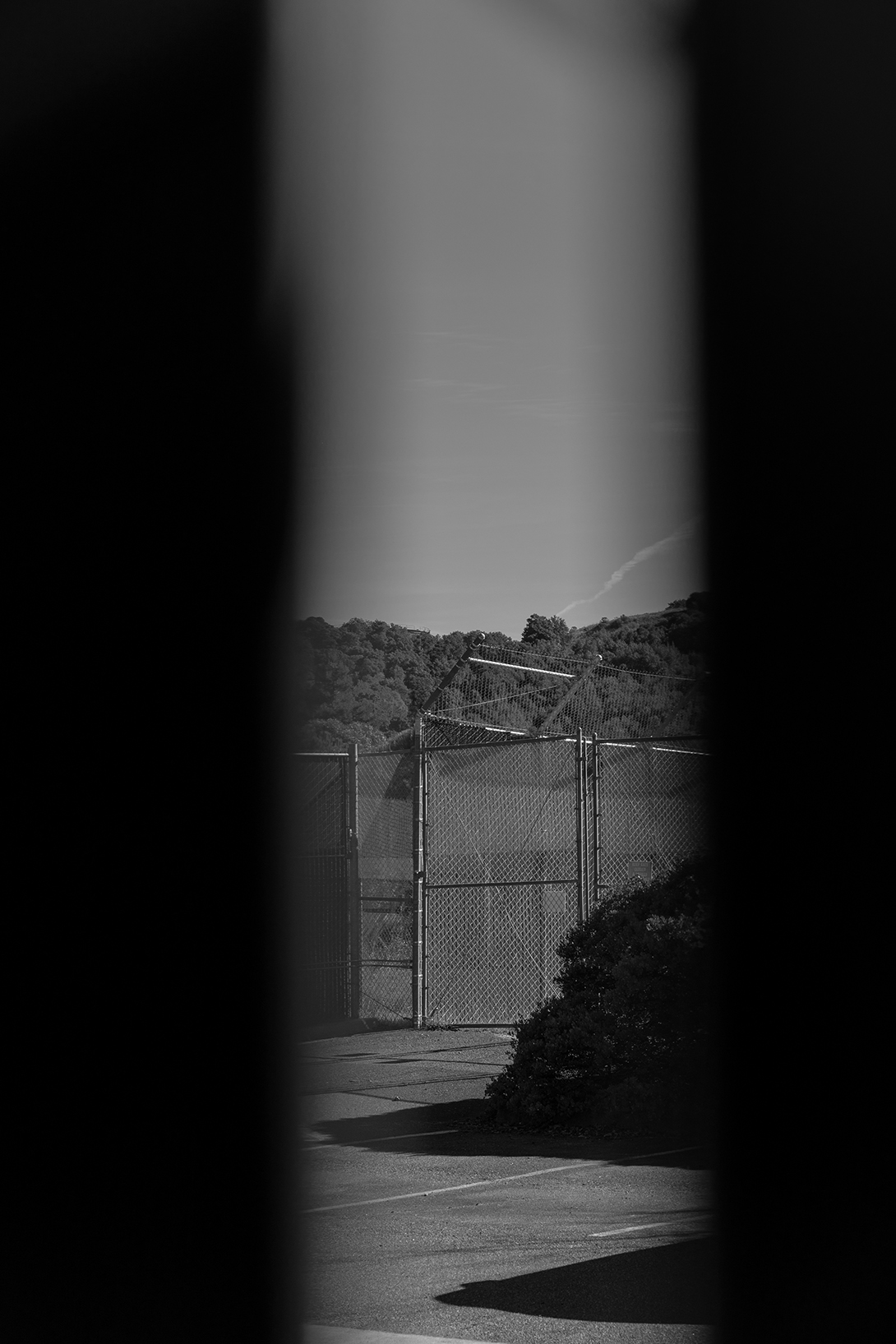

ONCE A WEEK, I’d leave my keys in a tray at the front desk, walk through a metal detector, look up at the surveillance camera and wait to be buzzed through a heavy door into a passageway where wild roses vined through chain link, then wait to be buzzed through another door with another camera, then walk past the security booth with the monitors. I’d say good morning to the staff and head to the classroom.

The students would shuffle in, single file, in identical orange sweat suits and plastic flip-flops, with their hands behind their backs, led by uniformed guards. They’d take their assigned seats and wait for their single sheets of paper and flimsy ballpoint pen inserts to be distributed. This was how I began every Wednesday morning in the year I taught poetry writing at the Marin County Juvenile Hall.

I never knew who would be there, week to week, or for how long. Some students were there for just a few days, others came in and out over the course of the year, and I got to know some of them. Ranging from baby-faced 12-year-olds to 17-year-olds who looked older, all were children, despite having already survived life experiences far more difficult than many adults will ever know. We weren’t allowed to ask them why they were there, though I was told that many had been involved in gangs and drug dealing, some in violent crime. An administrator warned me that they could be emotionally manipulative, but the main teacher, Ms. R, assured me they were actually sweet and eager to learn, and she was right.

The majority of the students were black and Latino, including immigrants and refugees from Mexico, El Salvador, Honduras and Guatemala, and nearly all had felt the devastating effects of racism, poverty and violence. Some had been convicted of or were awaiting trial for very serious crimes. I was told others were there for their own safety, removed from homes where there was abuse, addiction or neglect, or to be protected from human traffickers and violent threats. But is incarceration really safety? Surely there are better ways to protect our youth. And who was I to be there, some white lady poet from San Francisco who teaches at universities, doesn’t speak Spanish and has no prior experience or training in working with these young people? Given the differences between us, how could I connect with them? Why should they trust me, or anyone?

They didn’t always trust me, for valid reasons, I’m sure, and I didn’t always connect. This is not a movie cliche where an inspirational teacher dramatically turns around the classroom full of disadvantaged youth. The students’ participation in our poetry sessions was definitely incentivized. The points they earned could be used for extra personal calls. Whatever their motivations, most of them participated, and they had a lot to express. There were harrowing stories of trauma and hardship, drugs, violence, so many elegies. I’ll never forget M’s poem about the first time she saw her father smoke crack when she was a little girl, or K’s poem about seeing her brother get stabbed in the neck and trying to stop the bleeding with her own hands, being terrified he was going to bleed out before the ambulance came. Many of them wrote about loneliness, and regret, and the inside of their cells. Their poems were urgent, sincere, moving, funny, and often deeply personal, and they were brave and proud and trusting enough to read them aloud to each other.

We talked a lot about the power of vulnerability in poetry, the way the air in the room was charged when someone shared something vulnerable and true, how we could all feel that power, and they were amazingly supportive of each other’s expressions of vulnerability. Though I do believe vulnerability is powerful, I felt the tension of encouraging such expression in a place where displays of strength and reserve are acts of self-protection. There are times for self-protection and privacy. I tried to find a balance between when to encourage and not give up on the kids, as I think some of them had come to expect from teachers, and when to respect their space and agency, of which they had so little.

They wrote tough rhymes and accounts of trauma, but also tender tributes, hilarious, sly satires, and wistful poems about missing puppies, baby sisters and the smell of Mom’s cooking. The same boy who wrote a rap about guns wrote a sweet love poem to his girlfriend. I think of A’s poem about tending goats and chickens on his grandfather’s farm in Guatemala, and his beautiful tribute to his mother, who risked so much to cross multiple borders and bring her children to the U.S., and how much he wants to make her proud. They wrote about hearing corridos from open car windows, about feeling Grandma’s hug, and about starry night skies, ocean waves, and so much about love. Some poems were based on memories; others were imagined.

Imagination is powerful. Real change must first be imagined, conceived of, held and protected. We have to be able to imagine a better future in order to make change. We talked about this in class, and they often wrote about their plans and hopes for the future. V wanted to be both a therapist and a stylist so she could offer counseling while doing hair; J wanted to study criminal justice and become a juvenile detention officer so she could help other kids like her. When asked to write poems about their ideal futures, they wrote about living with their big families, tending gardens, growing their own food, working on houses and fixing cars, and about money, which is to say security and opportunity. They imagined being able to fix what they saw as broken, and create the shelter and safety they sometimes lacked.

I would tell you more about these brave and bright students and their amazing poems, but they’re not my stories to tell. After all, I was only there once a week, and at the end of our time, a walkie-talkie blurt would interrupt the students’ voices, and staff would collect and count the flimsy pens. The students would line up with their hands behind their backs, as though in anticipation of being cuffed. They’d be led back to their cells, while I’d be buzzed out, through the locked doors and chain link, back through the metal detector, to retrieve my keys and exit, finally, into the relief of the bright sun. They are not my stories, but it was an honor to help create a space for them to be written and shared behind locked gates, in a place where wild roses climb and bloom through chain link, in a world that isn’t as free as it should be. I’m committed to working to change that. If incarcerated youth can imagine such a future, we owe it to them to make it a reality.

This article originally appeared in Marin Magazine’s February 2020 issue with the headline: “The Power of the Word”.

How to Help

For more ways to support local businesses, go here.