“I thought I was the last one,” reflects Lucina Vidauri in her Sausalito home. A native Coast Miwok descended from Olompali, once the epicenter of Coast Miwok culture, Vidauri adds, “Never in my wildest dreams did I think, yes, they’ll come back.” Her words encapsulate the recent revival of Coast Miwok culture in Marin County, a renaissance that seemed unimaginable just a few decades ago.

For nearly 4,000 years, the autumnal equinox has shaped the spirit of Marin’s inhabitants. Each September, retreating fog reveals golden rolling hills and ushers in the warm harvest season. While modern Marin enjoys bountiful farmers markets, wine crushes and apple and pumpkin picking, the ancient Miwok people celebrated the autumn equinox with “The Big Time” harvest ceremonies — a tradition that endures despite historic tragedies.

Ancient Miwok life and traditions

Long before Marin became home to modern techies and 1960s hippies, prior to the shipbuilding and redwood logging eras of the early 1900s and preceding California statehood in 1850 and the Spanish missionaries from 1769 to 1833, the region remained largely untouched by outside influence. During this time, Marin was a pristine, abundant landscape, home to the ancient Miwoks, the region’s First Peoples. More than 600 village sites of Coast Miwoks existed between the Bodega Bay region and southern Marin County, comprising one of the most densely populated areas in all of North America, according to Marin Agricultural Land Trust (MALT).

Contrary to some anthropological assumptions, the Miwok were not purely nomadic hunter-gatherers. Sky Road Webb, a Coast Miwok from the Tomales Bay band and founding member of the Coast Miwok Tribal Council, clarifies: “Nomadic refers to having no home, which isn’t true. We were territorial and tended the land for thousands of years.”

Webb explains that the Miwok were also agrarian, actively managing their environment: “Miwoks planted oak trees. Some grandmothers preferred different flavors and strains of acorn, whether black oak or live oak. They were passed down from generation to generation. We even had oak doctors for oak health.”

The local cornucopia of ancient Coast Miwoks was diverse and abundant. It included elk, deer and antelope, as well as a rich variety of seafood like kelp, crabs, clams, abalone, mussels, oysters, salmon, rockfish and waterfowl. Plant foods were equally plentiful: blue elderberries, Pacific plums, California laurel fruit, roots, nettle leaves, clover and Indian lettuce. Edible mushrooms such as chanterelles and oyster mushrooms were gathered, alongside buckeye and other flower seeds like buttercup and goldfields. But no other food was more cherished in the Miwok diet than acorns.

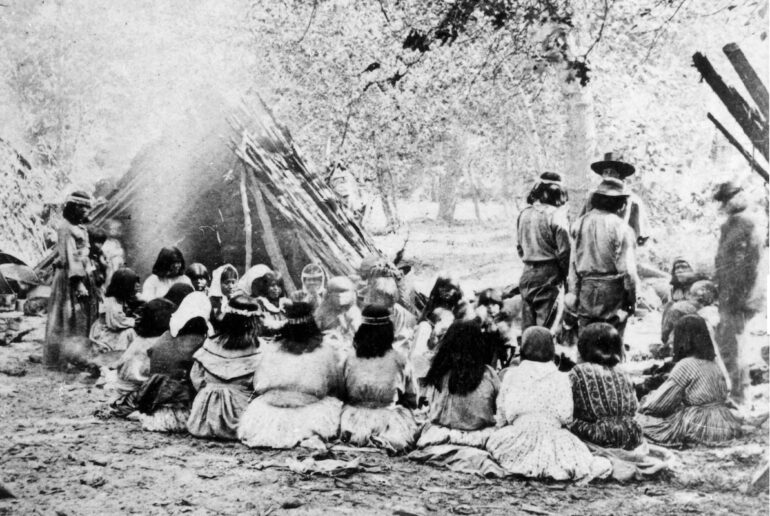

Each year, the Miwok community gathered for “The Big Time,” a celebration of their acorn harvest that was crucial for winter sustenance. Webb describes the process: “When acorns drop, it takes a lot of people-power. We rallied troops to gather the acorns, dry them out and store millions in granaries.” Traditionally, each family had its own acorn granary and participated in processing the ripened nuts, and the celebrations that followed.

The preparation of acorn flour was time-consuming. “The acorns were ground into meal in bedrock mortars. Once the tannins are leached out by repeatedly rinsing the flour in fresh stream water, the flour needs to be cooked right away while it’s wet,” Webb explains. “It cooks in tightly woven baskets with hot rocks… fluffs up in 4–5 minutes.” The resulting flour was used to make soup, mush or bread. Webb adds, “Some years the acorns don’t do well. We’d collect buckeye nuts instead, which need to cook longer. These were our staples.”

Acorns, a native superfood, are rich in protein, carbohydrates, phytosterol fats and minerals like calcium, magnesium and iron. But for the Miwok, oak trees represented far more than nutrition. Their relationship with these trees was familial in nature, illustrated by Webb’s recollection of a Miwok elder’s wisdom: “When asked why the oaks were dying of Sudden Oak Death, she said it was because we were no longer taking care of them. They are dying of broken hearts.” This highlights the deep respect the Miwok people had for their natural environment, which they diligently stewarded.

“In the Big-Time ceremonies, female dancers tapped the oak trees with sticks,” Webb notes. “Similarly, shaking them for acorns to drop stimulates the trees like a massage and makes them resilient. Dead branches were also removed.” These practices, along with prescribed burns, are now being recognized as methods for maintaining forest health and potentially reducing diseases like Sudden Oak Death.

Another significant autumn tradition involves cutting and drying tule grass, which is essential for constructing traditional Miwok homes, basket weaving and crafting canoes used in trading and hunting expeditions. Trading played a vital role in Miwok life, strengthening intertribal relationships and fostering a sense of community.

The ancient Miwoks, known for their maritime expertise, left a lasting legacy that continues through Sausalito’s seafarers. For thousands of years, these ancient people traveled long distances in tule canoes, using clam shells as currency for trade. One of the most impressive mariners and the namesake of Marin County was Miwok Chief Marin, whose knowledge of the bay’s tides and currents made him valuable to Spanish missionaries; they changed his name from Huicmuse to Marino (nicknamed Marin). Miwoks navigated rough Pacific waters and the San Francisco Bay, regularly canoeing up the Delta to the San Joaquin-Mokelumne Rivers and into the vast wetlands of the Sierra foothills, where the Valley and Sierra Miwoks flourished. An estimated 25,000 Miwoks existed between Yosemite and the Marin coast prior to 1769.

A legacy of struggle and survival

Like all Native North American peoples, the Miwok bore the scars of colonization. Spanish missions disrupted their way of life, imposing forced labor and evangelization. The introduction of European diseases led to the first significant decline in native populations by more than one-third. The San Rafael Arcangel mission, founded in 1817, aimed to treat sick Indians.

After California became a U.S. state in 1850, conditions deteriorated further for native populations. The Gold Rush led to enslavement, displacement and discrimination of California’s Indians. California’s first governor, Peter Hardeman Burnett, infamously declared during his second State of the State Address in 1850, “That a war of extermination will continue to be waged between the races until the Indian race becomes extinct must be expected.”

As documented in “The Secret Treaties with California’s Indians” from the National Archives, the U.S. Senate secretly declined to ratify 18 treaties with California tribes in 1852, thereby revoking commitments to provide land and protection for Native Americans in the state. During the 1950s, many Indian rancherias were terminated under federal policies aimed at assimilation. Despite these challenges, the Miwoks persevered. After a century of fighting, some Miwok tribes regained federal recognition in the early 2000s.

In 2019, Governor Gavin Newsom made a formal public apology to California’s tribal leaders for the historical violence and genocide. He stated, “We can never undo the wrongs inflicted on the peoples who have lived on this land that we now call California since time immemorial, but we can work together to build bridges, tell the truth about our past and begin to heal deep wounds.”

Contemporary renaissance and voices of tomorrow

Today, modern Coast Miwoks are experiencing a cultural resurgence, showcasing their enduring spirit and dedication to the principles of connection and balance with their ancestral land. This revival comes after generations of displacement and cultural suppression. As Lucina Vidauri explains, “Our culture didn’t survive — for seven generations. After thousands of years living peacefully, the Coast Miwoks were driven out of Marin in 20 years’ time, or killed off — from disease and genocide.”

Vidauri, a court reporting assistant by day, has become a passionate educator of Miwok culture through her website, MarinMiwok.com, and its Facebook page. She inherited her father’s manuscripts — 1,000 pages documenting Miwok history and traditions — which she is now preparing for publication.

There were deep wounds to navigate. She describes the emotional challenges in revitalizing the community: “Sadness and anger arose from a historical lack of respect and acknowledgment for Miwok history. Figures like Father Junipero Serra and Sir Francis Drake were commemorated with street names, schools and statues in Marin.” Serra enslaved Native Americans, while Drake was a British slave trader.

Possibly inspired by the broader social movements like Black Lives Matter, Miwok cultural events and gatherings began to see a comeback among the approximately 3,400 descendants of the ancient Miwoks, according to the last census. The Miwok Acorn Festival, which has regained its status as the most significant event of the year over the past decade, is now celebrated at various locations, including Miwok Park in Novato, Point Reyes National Seashore, Grinding Rock State Park, Sacramento and Tuolumne. These sites often feature reconstructed cha’kas — ceremonial roundhouses representing Mother Earth — as well as traditional Miwok bark-covered homes made of redwood or cedar. The festival includes traditional dances, hand games, singing and storytelling.

“Right before the pandemic, I began hosting gatherings in Marin,” Vidauri recalls. “I was amazed when nearly 100 people attended, and in San Geronimo, some of whom were mixed Coast Miwok descendants.” Participants processed feelings of grief and anger. “I suggested to them, ‘It’s time, come back!’” she emphasizes, underscoring the emotional journey of reclaiming their cultural identity.

These gatherings rekindled a long-lost sense of ancient community in Marin, leading to the establishment of the Coast Miwok Tribal Council of Marin, a governance body formed under Public Law 93-638. This model of ‘self-determination,’ Webb notes, ‘provides greater autonomy in governance compared to the federally recognized ‘tribal sovereignty’ model.’ While gaming revenue can offer significant benefits to federally recognized tribes, not all California Natives identify with the casino industry. The complexities of tribal governance today, reflected in issues such as membership dis-enrollment and election disputes, reveal the diverse perspectives and unique paths each tribe navigates in preserving their heritage and autonomy.

In the recent year, the Coast Miwok Tribal Council achieved a significant milestone by raising $1 million to purchase 26 acres of ancestral land in Nicasio for Coast Miwoks. “We’re very grateful to Marin County. They helped buy the property for us to reform our village. We were scattered. Now we have blessed the land for gatherings and for our people to come back to,” Webb adds.

Theresa Harlan, another Coast Miwok descendant, is pursuing historic-district status for her family’s homes and access to host native gatherings within a National Park Service jurisdiction. Her family, the Felixes, lived at Marshall Beach and Felix Cove until they were forcibly evicted by ranchers in the 1950s. Harlan emphasizes, “This land is part of our creation story. It’s where we come from. And it’s where we need to be to continue our traditions and our culture.”

Recent developments at the state and federal levels have shown promise for tribal interests. In April 2024, California announced $107 million in grants for tribal co-stewardship and nature-based solutions, supporting buybacks of 38,000 acres of private lands once occupied by indigenous tribes. At the federal level, Secretary of the Interior Deb Haaland, the first Native American to serve as a cabinet secretary, has been instrumental in advancing tribal interests, stating, “Restoring tribal lands is not just about righting historical wrongs; it’s about empowering indigenous communities to be the stewards of their ancestral territories.”

Progress continues to be made. “Offering respect and acknowledgement to Miwoks is a new positive change,” Vidauri notes. “Many businesses are acknowledging that they are on Miwok land, which is unceded land. Curriculum in schools is changing now.”

“It’s most important to reach the children,” she says, drawing from her own experience of learning Miwok oral history from her father. Her great-great-grandfather was Chief Camillo Ynitia, the last chief of Marin and a friend of the famous Chief Marin during the missionary period.

Looking to the future, Vidauri envisions more positive cultural events and a cultural center. “I would like to have more Powwows and ‘cultural days’ in Sausalito and greater Marin,” she says. “We don’t want to be known for the 20 years of violent turmoil that drove us away. We want to be known for our peaceful ways and customs.”

Efforts to preserve and share Miwok culture are ongoing. Sky Road Webb contributes to this mission through his many roles: Councilman of the Coast Miwok Tribal Council, President of both the Marin American Indian Alliance (MAIA) and the Miwok Archaeological Preserve of Marin (MAPOM), and advisory board member for the Museum of the American Indian and the Miwok Archaeological Preserve of Marin (MAPOM). As a master storyteller, Webb plays a crucial role in passing down Miwok traditions and knowledge to future generations.

Webb announces, “MAIA’s 3rd Annual Marin Powwow, which is open to the public, will be held mid-March next year in a San Rafael high school gym, featuring Powwow drum and dance, California Indian Big Time dance, Azteca Danza, Hawaiian hula, fry bread and vendors.” These events offer Miwok and non-Miwok community members, especially younger generations, opportunities to experience and appreciate Coast Miwok culture.

The Miwok people’s story is one of resilience, adaptability and revival. As we observe Native American Indian Heritage Month this November, we honor their legacy by exploring the Miwoks’ rich history and ongoing contributions to the cultural and ecological fabric of Marin. Future issues will feature Miwok mythologies, diverse perspectives and detailed views of their historical tapestry and enduring legacies.

This harvest season, consider participating in native autumnal activities like the Miwok Acorn Festival or Trade Feast. We also invite readers to share what they would most like to learn about Miwok culture and history.