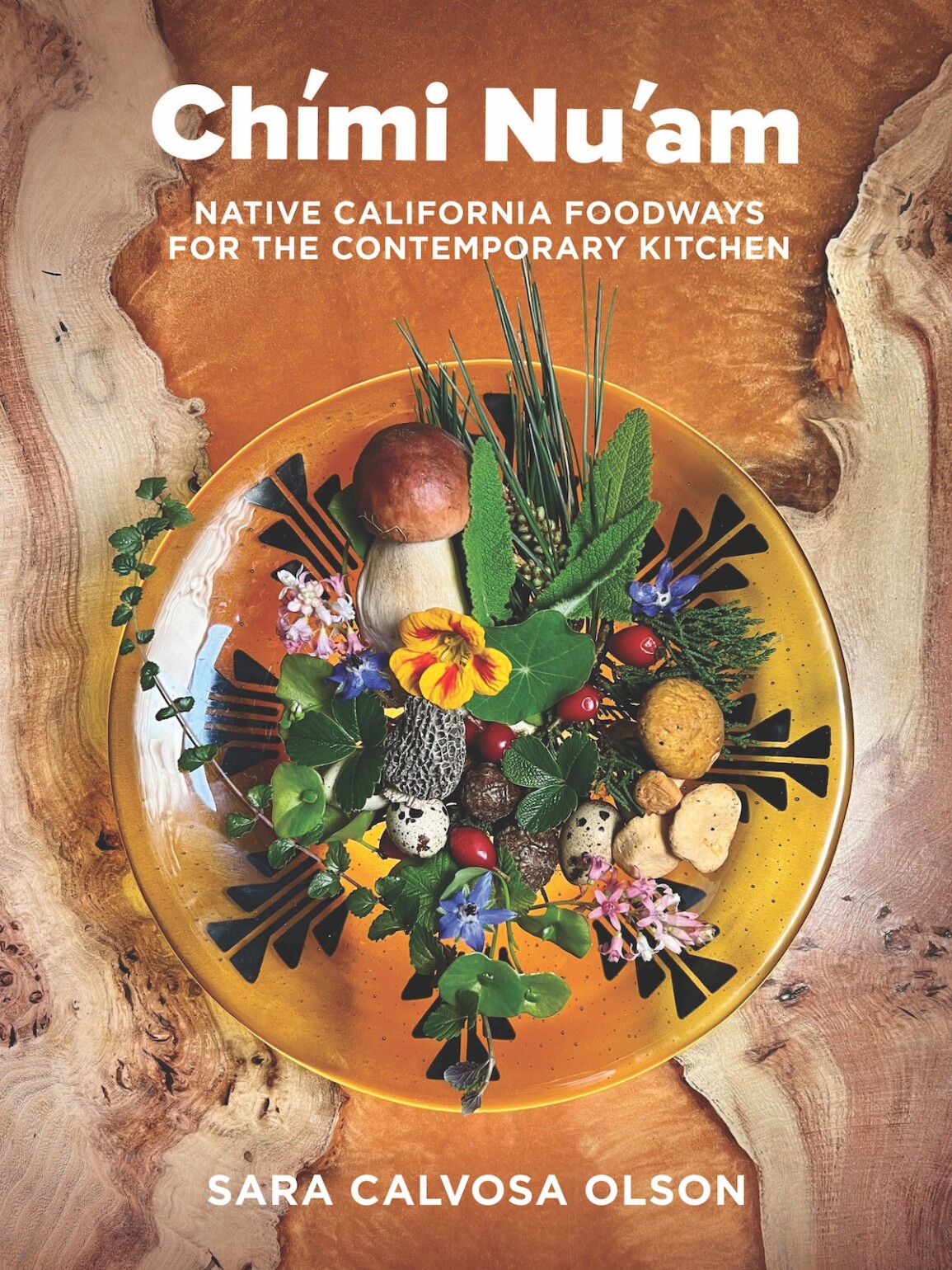

Are you on a food journey? Do you eat keto or paleo, avoid certain foods or been told by a health professional to change your diet? Food and how we eat is intensely personal, defined by how and where we grew up, who taught us to cook (or not), individual health needs, and the value we place on convenience and the local food shed. Mill Valley resident Sara Calvosa Olson is a home cook and author of Chimi Nu’am, or “let’s eat” in Karuk, the language of the eponymously named Indigenous peoples whose ancestral lands span Humboldt and Siskiyou counties.

Calvosa Olson, who is Karuk on her mother’s side and Italian on her father’s side, launched her food journey when her children were little. “I wanted my children to feel connected to this community and flowed into that through food,” Calvosa Olson says. The eldest granddaughter and eldest child, Calvosa Olson also felt a responsibility to learn Indigenous lifeways.

Bridging Indigenous and Western Foodways

As a child growing up in Hoopa, Calvosa Olson’s family ate from a hybrid of food sources. Her parents planted a large garden and preserved its bounty. Hunting, fishing and foraging were regular events. And the government provided commodity boxes with milk, cheese and other western staples. She grew to appreciate the flavors inherent to the California foodshed — fishiness, bitterness, earthiness — and to notice the disconnect between where our food comes from and how it gets to the plate. “It’s complicated,” Olson says. “You’re battling an entire systemic machine with a long history. It’s hard to extricate yourself.”

Calvosa Olson’s cookbook seeks to rebuild the lost connections to the natural bounty of Northern California while sharing how she and her family cook and eat. Recipes, like acorn manzanita waffles, wild boar pozole and peppernut mole chicken tacos, embrace seasonality and maximum utility of local ingredients. You cannot get all the ingredients called for in the 75+ recipes at a supermarket. That’s Calvosa Olson’s point. “What if you went on a different journey about food?” Calvosa Olson asks. “And doing it by centering Indigenous people the right way?”

The Journey is the Point

Acknowledging that her cookbook is “super-inconvenient,” Calvosa Olson suggests beginning a Native foods journey from a comfortable place. Start with what feels right. Comfortable using a smoker? Start with the blackberry-brined smoked salmon in summer. Then try the miso smoked salmon chowder hand pies in winter.

Don’t know where to get elk for the Elk Cottage Pie? “That is the start of your journey,” says Calvosa Olson. As part of the ‘figuring it out’ that is part and parcel of cooking from Chími Nu’am, Calvosa Olson encourages readers to forge deeper, more meaningful connections with their community. Ask questions — maybe your neighbor knows how to fish or your child’s teacher goes foraging for mushrooms. As you build these networks to Native foods, you become embedded in our local food shed. And that is the point. You are then actually becoming a part of the real community, “the one that matters, the environment.”

Look over the recipes to consider which of the many in Chími Nu’am could be the start of an Indigenous foods journey. Cataplana, a Portuguese, wintery seafood stew, asks for local seafoods found at a local market or from Pacific Native Seafood, a Native American owned, family-run business in Bodega Bay. Red chile rabbit tamales blend Mexican and Native traditions; the butchers at Mill Valley Market often have rabbit in the back (as well as elk and bison). And the cedar tips that fragrance beet-pickled quail eggs are as close as your or a neighbor’s backyard. Calvosa Olson suggests making familiar substitutes to support the journey. If elk is a bridge too far, try beef. No Tepary beans, a legume native to the American southwest, for a soup with ham hock and collards? Navy beans are easy to find.

In Community, Together

There’s an openness to Calvosa Olson’s style of cooking, an embrace of what’s close at hand, making use in winter of what’s preserved from summer, or what a neighbor shared from their garden. And a reframing of abundance. For many, thinking about food this way — as a community effort that supports the land and its Native people — is a radical perspective shift, one Calvosa Olson acknowledges. Reciprocity is not ingrained in the rugged individualism that is a built-in aspect of the American brand and way of life. Calvosa Olson’s hope with Chími Nu’am is that you, too, will connect with and support the Indigenous community on whose land we all make our homes. “Can you put something back in?,” she asks. Contribution not acquisition. Share your abundance without expecting anything in return. Is this radical or humble? Perhaps this radical/humble idea can be a part of your food journey, too.

Chími Nu’am — let’s eat!

Wild Boar Pozole

Southwest Indigenous cultural lifeways have left an indelible imprint on our California foodways. Pre-colonization, California tribes didn’t recognize state boundaries, freely migrating and trading with one another. The wide variety of foods and flavors, especially coming through Southern California tradeways, are the height of innovation when it comes to creating dishes with preserved and dried foods. Dried chiles, nixtamalized corn, dried spices and herbs—pozole embodies the flavors of Indigenous culinary refinement and style in a single bowl of soup. Also get ready to make a lot of dirty dishes, as this recipe is something you’ll spend a couple of days preparing. But it makes enough for you to be able to eat it again as delicious leftovers or freeze for another day when you just need some spicy comfort food.

Ingredients

- 9 to 10 dried chiles (I mix it up with guajillo, ancho, New Mexico, or California chiles)

- 1½ large white onions

- 2 or 3 garlic cloves

- 2 pounds wild boar (or pork shoulder), cut into stew-sized pieces

- Salt and pepper

- 1½ pounds of dried hominy/pozole

- 1 lime, cut in half

- 5 whole cloves

- 1 fresh bay leaf or

- 3 to 5 dried bay leaves

- 1 2-inch strip of dried kombu

- 1 bundle of fresh epazote or mugwort and cilantro tied together with string, about 2 ounces of each

Preparation

Garnishes: Cilantro, shredded cabbage, diced or sliced jalapeños, thinly sliced radishes, lime wedges, avocado, escabeche, toasted sesame seeds or pepitas

Serves 4 to 6

Put on rubber gloves, because nobody wants red chile eyeballs—trust me, you will absently rub your eye and be sorry. Cut the chiles down the length and remove their seeds, stems, and veins. You want your chiles to be pliable and bendy if possible. If they are brittle, handle them gingerly.

In a large cast-iron pan, lightly toast the chiles over medium heat until fragrant, but keep an eye on them; if they burn, you’ll have to start over because your soup will be bitter.

In a medium saucepan, add the chiles and a few cups of water, just enough to cover them by a ½ inch. Bring to a boil over high heat, and then turn off the heat, letting the chiles steep for 10 to 15 minutes.

While they’re steeping, char ½ onion and the garlic in the same castiron pan you used to toast your chiles. Transfer them to a blender.

Using tongs, pull the chiles from the water and add them to the blender too. Pulse until the mixture becomes a thick paste, adding a couple of tablespoons of water if needed to break everything down.

In a large bowl, liberally season the wild boar with salt and pepper. Add half of the chile paste to the wild boar and stir to coat. Cover the bowl with plastic wrap and allow the meat to marinate in the refrigerator overnight. (Save the other half of the chile paste in the refrigerator for the next day.)

Soak your hominy/pozole overnight as well.

The next day, remove the bowl with the wild boar from the fridge and allow the meat to come to room temperature. Pour off the soaked hominy water. Char the lime halves in a cast-iron pan.

Put the drained hominy/pozole into a large Dutch oven and fill water all the way to the top.

Peel the remaining onion and slice off the ends, poking cloves into the top and bottom. Add it to the hominy along with the bay leaf, kombu, charred lime, and escabeche and cilantro bundle.

Bring to a boil over medium-high heat for about 10 minutes. Cover and reduce the heat to a barely detectable simmer for 1 hour; you don’t want your hominy to bounce around and break up.

After an hour, remove and discard the kombu and lime and add the boar to the hominy.

Bring back up to a boil, then turn down to a simmer, cover, and cook for another 1 to 2 hours until the meat is easily shreddable and the hominy is tender and chewy. Stir in the remaining red chile paste, adding salt and pepper to taste.

Serve in bowls with a plethora of garnishes—the garnishes are co-workers in this soup, so the more the merrier.

White Tepary Bean Soup

Tepary beans are an incredible traditional superfood, high in protein, with a low glycemic index. They’re so drought tolerant that the Tohono O’odham can grow them on the water from desert monsoons alone. In fact, they are the world’s most drought-adapted domesticated bean. Little badasses. They are denser than regular beans, and there is a marked sweetness that goes well with smoky ham and umami collards. In this recipe and always, it’s important to wash your vegetables very well in cold water. You don’t want any gritty soil left on your collard greens or chard.

Ingredients

- 1½ cups white tepary beans, rinsed and sifted for pebbles (see Note)

- 1 large ham hock, split

- 1 leek, white part finely chopped, green part reserved separately

- 1 2- to 3-inch piece of dried seaweed, such as Pacific kombu

- 3 juniper berries

- 1 bouquet garni (a “bundle of herbs” made up of bay leaf, thyme, and parsley, wrapped in cheesecloth and tied with a string, 2 to 3 ounces altogether)

- 8 cups water

- 1 bunch of collards, chopped into 1-inch pieces

- 1 tablespoon Worcestershire sauce

- 2 tablespoons olive oil

- 1 tablespoon finely chopped fresh rosemary

- 1 teaspoon white pepper

- 3 garlic cloves, finely chopped

- 1 to 2 cups wild mushrooms, cleaned and sliced or chopped

- 1 bunch of chard, chopped Rustic

- Acorn bread (page 30), for serving

Note: If you would like to make this a creamier soup, remove a couple scoops of beans and broth before adding the mushrooms and leeks. Blend the beans in a blender and add them back to the pot with everything else.

Preparation

Serves 4 to 6

In a large Dutch oven or stockpot with a lid, add the tepary beans, ham hock, the green part of the leek, kombu, juniper berries, and bouquet garni. Add the water. Bring to a hard boil over medium-high heat and allow it to boil for 10 minutes before reducing the heat to a low simmer for 1 hour.

Remove and discard the green leek, kombu, and bouquet garni and add the chopped collards and Worcestershire sauce. Cover the soup with a lid and continue simmering for 3 to 5 hours until the tepary beans are soft and the ham hock is falling off the bone. It’s all going to cook down together to make a delicious pot liquor soup.

Now, you can eat the soup just like this with some crusty acorn bread and it’s delicious. I’m extra, so I do the next step as well.

In a separate pan, heat the olive oil over medium heat and sauté the remaining chopped leeks until they begin to soften, 2 or 3 minutes. Add the rosemary, white pepper, and garlic and sauté for another 1 to 2 minutes. Add the mushrooms and chard and sauté until just cooked, another few minutes. Don’t overcook the chard if you can help it; you want it to still have some bite.

Before adding the contents of the sauté pan to the soup, use a slotted spoon to scoop the ham hocks into a bowl. Shred the meat and discard the bones, and return the meat to the soup along with the mushrooms and leeks from the pan. Serve with crusty acorn bread.

Miso-Marinated Black Cod

Black cod goes by many names, sablefish, butterfish and blue cod among them. Its indulgent texture and mild flavor also benefit from any number of preparations.

But few will tempt with the type of name or tastiness of what Mario Garcia, executive chef at Carmel landmark Grasing’s, does with black cod.

When the Trust requested a fun and easy recipe, he promptly unveiled what he titles “Monterey Bay-Caught Yuzu-Miso-Marinated Butterfish with Sesame-Ginger Soba Noddles and Crispy Garlic and Chili Bok Choy.”

That sounds incredible, and perhaps a little intimidating, but give it a chance. It’s sneaky doable and the type of recipe that can empower normies to take on a delicious local protein and win the potluck. It’s particularly good right now, when yuzu is in season. And the crispy garlic-chili sauce can be made ahead of time and goes great on all sorts of dishes.

Ingredients

- 5 6 oz pieces of black cod/sablefish/butterfish filets

- 6 each baby bok choy

- 1 cup aka (red) miso

- 1 cup granulated sugar

- 1 cup aji mirin

- 1 cup good sake

- 1/4 cup yuzu juice

- 1 package of soba noodles

- 1/4 cup sesame oil

- 1 medium piece fresh ginger (peeled and grated)

- 1/8 cup rice vinegar

- 1/2 cup soy sauce

- 2 tablespoons honey

- 1/2 cup shredded purple cabbage

- 1/2 cup julienne carrots

- 1/4 cup sliced green onion

- For crispy chili garlic

- 1/2 cup fresh garlic sliced

- 1/2 cup shallots thinly sliced

- 2 tablespoons red chili flakes

- 1 tablespoon toasted white sesame seeds

- 1 teaspoon sugar

- 1/2 cup sesame oil

- 1/4 cup vegetable oil

- 1/4 tablespoon soy sauce

- 2 bunches green onion chopped

- 1 medium piece fresh ginger sliced

- 1/2 teaspoon of kosher salt

Preparation

For the yuzu miso marinade, combine miso, sugar, aji mirin, sake, yuzu juice in a medium sauce pan on a medium high flame. Mix until well combined. Allow to simmer and reduce until liquid has thickened and a dark amber color has been produced. Remove from heat, allow to cool for 15 minutes. Add yuzu and mix well. Allow to completely cool and set aside.

Rinse and pat dry the butterfish. In a food safe container cover the butterfish with miso yuzu paste and allow to marinate for at least 12 hours (overnight is best). Remove butterfish from marinade wipe off any excess miso and place in roasting pan bake in oven at 450 degrees for 8-10 minutes until a deep golden caramelization.

For the crispy garlic-chili sauce: In a small pan heat vegetable oil and fry shallots until golden brown, remove from oil allow to dry and cool. Fry sliced garlic until golden brown remove from oil and allow to cool. Add ginger and green onion, allow to fry for 1-2 minutes, then remove ginger and green onion from oil. With infused oil at 350 degrees, in a small heat proof bowl add chili flakes, sesame seeds, sugar, soy sauce, add hot oil to mixture allow to slightly cool add crispy shallots and garlic and salt. Mix in until well combined

For the baby boy choy, bring a pot of water to a boil season with a 1/2 cup soy sauce. Cut box choy lengthwise in half and wash, then blanch until tender and remove from heat.

In a large pot bring water to boil, cook soba noddles until tender (5-6 minutes), stir occasionally so the noodles don’t stick. Drain in colander and rinse under cold water.

In a small bowl combine sesame oil, grated ginger, soy sauce, and honey, whisk together until combined, set aside.

In a hot medium sauté pan with a tablespoon of vegetable oil add julienne carrots, shredded cabbage, and green onion. Stir fry for 30 seconds, remove from heat. In a medium bowl add soba noodles, stir-fried vegetables and drizzle sesame-ginger mixture, toss until well combined.

Plate soba noddles, top with butterfish and baby bok choy, drizzle crispy garlic chili oil and serve!

If you want to explore the local food shed more deeply, Calvosa Olson is happy to talk about it. You can find her at @thefrybreadriot on Instagram.