In the San Geronimo Valley, there are four villages. The oldest is San Geronimo, second from the east. Historians have been trying to answer a seemingly straightforward question for decades: how did San Geronimo — the village and the valley — receive its name? This valley, even with a colonial history that spans over two hundred years and an indigenous history at least three thousand before that, has, it seems, been just far enough off the beaten path to have eluded in-depth historical research.

When J.P. Munro-Fraser wrote his 1880 History of Marin County, California, the settlement at San Geronimo is mentioned just a few times, and in passing — it was part of Nicasio township and had just ten homes (its train station was named “Nicasio/San Geronimo,” in that order.) Coast Miwok oral history doesn’t locate any year-round Native American village sites in the valley before the Spanish arrived in the Bay Area at the turn of the 18th century, and archeologists haven’t identified any either. There is a pervasive sense that the Valley was, and continues to be, an outlier.

Two historians have delved into the naming of the Valley, but neither were able to reach a definitive conclusion. Louise Teather’s 1986 Place Names of Marin suggests a theory — that its namesake is a Coast Miwok man baptized ‘Geronimo’ by the Spanish. But as recently as 2007, Marin historian Betty Goerke contradicts Teather’s thoughts in her book Chief Marin, and reminds us that further investigation is needed. How did this beautiful valley end up bearing the name of the Catholic church’s patron saint of archaeologists, librarians and students? How did the settlement of San Geronimo go from a single ranch to become the Valley’s community hub of today? And how do we reconcile the existence of slavery in a place that is now so peaceful?

I’ve found myself becoming steadily more fixated on this overlooked history since I started studying the San Geronimo Valley, maybe because I can’t help but feel that there is more at stake than just knowledge of a place name for my hometown. It feels like there is an opportunity, in finding the answer to this question, to in some small way begin to make right a terribly imbalanced historical narrative, one that has heavily favored colonists’ voices over Indigenous Peoples’ truths.

We are at a juncture where, in a world that is increasingly spreading outwards, people are more and more looking to root down in their communities. We see this in the local and organic food cultivation movements, and in land conservation, especially in Marin County. But when it comes to the history of the Americas, embracing place means uncovering painful truths about the treatment of Indigenous Peoples and coming to terms with them. It also means feeling encouraged by an understanding of how thousands of years of Native American knowledge can help us move forward more gracefully in place, and how descendants of these tribes are still very much here, striving for the preservation and continuation of their cultures.

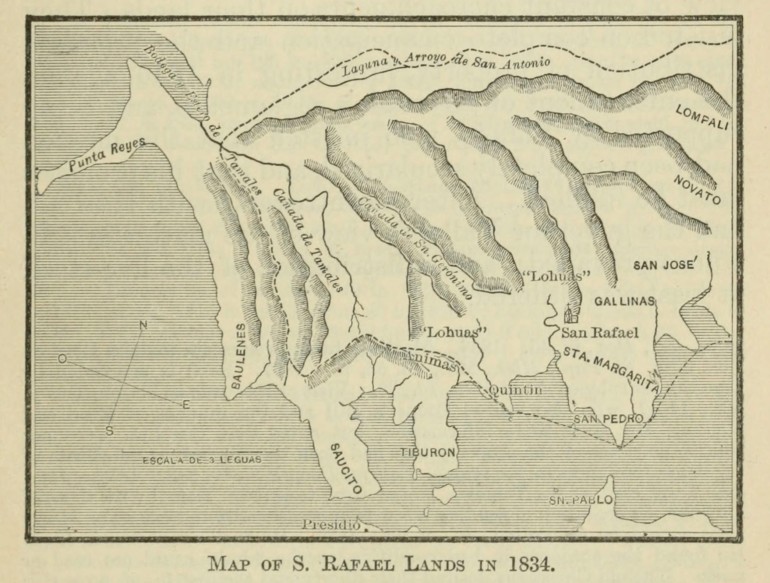

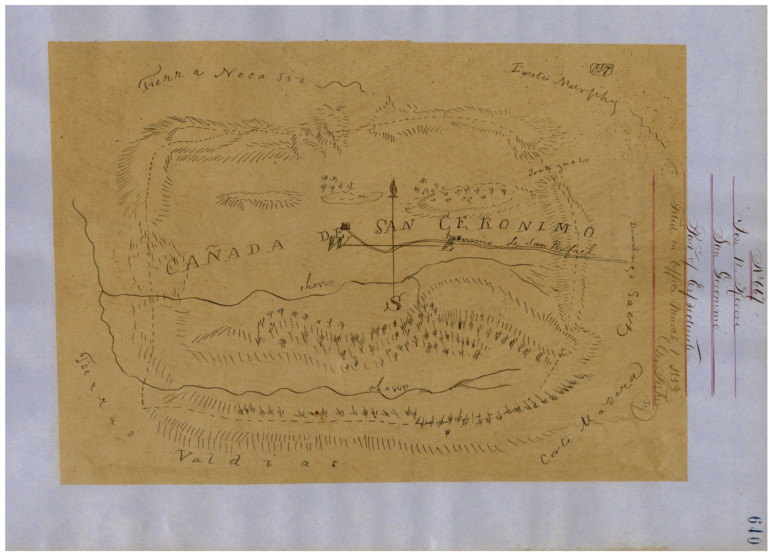

We do know a few things for certain: San Geronimo was the first colonial settlement established in the Valley proper. The name La Cañada de San Gerónimo (Spanish for ‘San Geronimo Valley’) was in place by 1834 when it appeared on a map of former mission lands in the area we now know as Marin County. Most remarkably, we know there surely was a Coast Miwok Native American named Jumle who was about 24 years old when he was baptized Geronimo at San Francisco’s Mission Dolores on April 23, 1808. Geronimo advanced in status through the mission system. He was recognized for his skills as a vaquero (cowboy), reaching the level of alcalde, a type of overseer position that granted him some authority and a certain amount of freedom to leave Mission San Rafael for official mission business — for one, some think, to tend to herds of livestock in the San Geronimo Valley.

Armed with this foundational knowledge and a healthy dose of speculation, Goerke and Teather come to two different conclusions. Teather seems to have found evidence that the San Geronimo Valley was named in honor of this valued Coast Miwok alcalde. But Georke thinks it’s unlikely that the Spanish would place the honorific San (Spanish for “saint”) in front of an Indigenous person’s name. She suggests that the San Geronimo name had some other, still unknown, derivation. Perhaps both theories are correct. Maybe Geronimo was so much associated with the area that “Geronimo,” his baptismal name, stuck, and the “San” was later added in the tradition of Spanish place saints’ names across the state.

We know for certain that this happened in nearby San Anselmo, which had earlier been known as La Cañada de Anselmo. Anselmo was the baptized name of the alcalde who sometimes oversaw the area now known as San Anselmo under Mission San Rafael. Without further examination of correspondence between mission officials, we can only guess, but San Anselmo gives us a crystal clear parallel model, and I am motivated to uncover the full story.

A disturbing truth we do know is that subjugation of Native Americans was the basis of the mission system — including in Marin. By 1833, the system of Native American forced labor that made the existence of Mission San Rafael possible was coming apart at the seams during the secularization of California’s missions. Mexico had become independent of Spain in 1821 and had been gradually dismantling the Spanish mission system from within in part to distribute mission lands to Mexican settlers. During this time the missions’ Native American inhabitants were to be released from servitude and the missions’ property was to be distributed. All said and done, it had taken just 57 years for colonizers to destabilize thousands of years of relatively peaceful Coast Miwok cultural growth and existence.

By 1850, in the wake of the mission system’s demise, the last traditional Coast Miwok villages were all the way north in Bodega Bay, while mission survivors formed settlements across Marin. Back in San Geronimo, a Mexican military officer named Rafael Cacho had been taking advantage of the upheaval of Mission San Rafael’s demise by freely grazing cattle in San Geronimo as early as 1839 on land that should have been the Miwoks’. The Coast Miwok had been promised by the Mission a fair allotment of the former Mission’s land and property holdings, but instead many were coerced into working for Mission San Rafael with nominal compensation, even after its official closing.

Meanwhile, the livestock, the Mission’s greatest material asset, were siphoned off to colonial landowners like General Mariano Vallejo and Timotheo Murphy under the auspices of “safe keeping.” Joseph Warren Revere, grandson of Paul Revere, describes purchasing the San Geronimo Valley in 1846 from Cacho in his 1878 autobiography Keel and Saddle. During his four years as rancho owner, Revere raided, captured and enslaved Coast Miwok from the Bodega Bay area, ostensibly as retribution for a horse theft, ordering them to produce adobe bricks for building on the San Geronimo rancho. His adobe home was near the southwestern corner of the former golf course property, just across Nicasio Valley Road from the San Geronimo Community Presbyterian Church of today.

His perspective was quite typical of colonists of the era. “The prisoners thus pressed into our service were divided equally among our party, submitting resignedly and even joyfully to their fate,” he wrote in Keel and Saddle. He lauds the success of his party’s raid on the Bodega Miwok rancheria where he and his ranch-owning allies fired “shot after shot” against the Miwoks “ruder Indian weapons.” This wild account definitively places enslaved labor in the San Geronimo Valley sometime between 1846 and 1850.

Today, 175 years later, if you walk the green open fields of the former San Geronimo National Golf Course on a warm spring afternoon, you can almost feel the weight of the land’s past and these accumulated centuries of history. Despite this burden, the land is resilient and forgiving, and it’s not hard to imagine why people have gravitated for hundreds of years to this bright sunny spot that is nearly at the geographic center of the San Geronimo Valley floor.

There is more to learn about the town of San Geronimo and Jumle’s presence in La Cañada before his death in 1824. Where did he live? Did he indeed operate a ranch, and what was its extent? Who were the Miwok who tended the ranch with him, if any? Was the San Geronimo Valley or the settlement of San Geronimo first to receive the name? And so, our original question leaves us with many more.

In the same harsh reality where the US economy was built on the backs of enslaved African Americans, in Marin and across California the painful truth is that Indigenous Peoples’ slavery and coerced labor built our early economy, paving the way (sometimes quite literally) for its future growth. Whether or not we will ever know the exact truth behind the geographic place named San Geronimo is important, but it is less meaningful than the truth before our eyes: it is long overdue that Marin’s Native American voices take their rightful place at the forefront of the county’s past and present.

Today’s Coast Miwok descendants have no land in Marin County — many live outside of and far from Marin, yet visit frequently with their families and feel a powerful connection to the earth here. Maybe, someday soon, we can find a way to return some pieces of this paradise to the descendants of its original inhabitants. If we could, it would be a start.

How to help:

There are many ways to learn more about the Coast Miwok people: marinmiwok.com (run by coast Miwok activist Lucina Vidauri), Betty Goerke’s Chief Marin, the book Interviews with Tom Smith and Maria Copa, edited by the Miwok Archeological Preserve of Marin (MAPOM), and Dawn of the World by C. Hart Merriam are just some. MAPOM also offers classes and events led by Coast Miwok culture bearers on their culture and history.