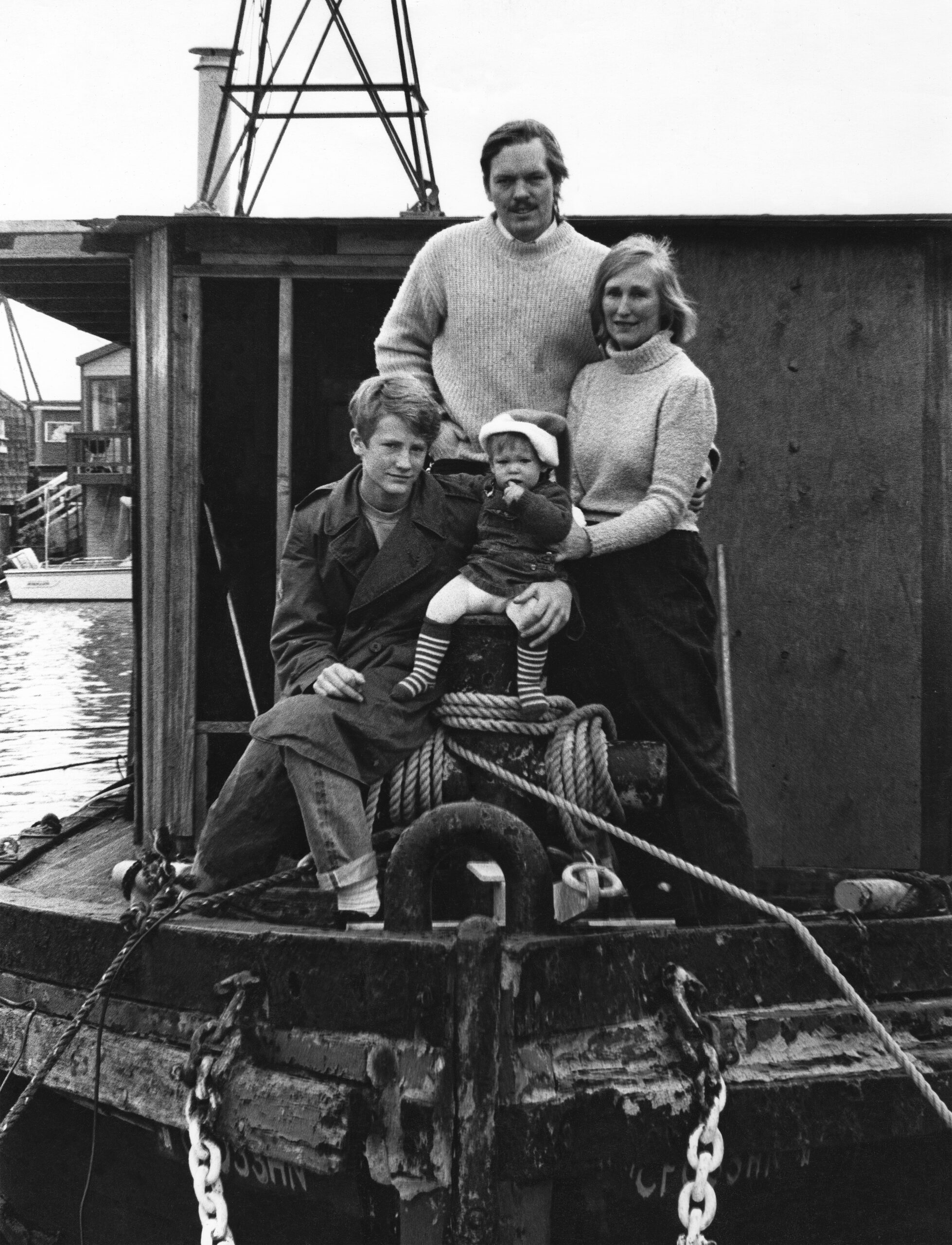

Bohemians, artists and renegades — that’s how most describe the people who lived on abandoned World War II vessels in the decades after the shipyard closed. The truth of that era, however, is as complex and diverse as the individuals and the kids they raised.

Unsurprisingly, the waterfront children of the ‘70s grew up with a freedom unheard of for youth today. They roamed the docks in packs and learned early the value of community.

Their wild and free upbringing wasn’t great for everyone. “There’s a pretty long list of people I grew up with who are not around,” said Tahoe Boaz, noting that some died and some have been imprisoned.

Yet many others have thrived, shaped in positive ways by their unconventional childhood. Here are five individuals who, although they have moved off the docks, continue to contribute to the community they still love.

Tahoe Boaz

Southern Marin firefighter Tahoe Boaz is doing what he always wanted. “I’m super lucky to have my dream job in my hometown,” he said. “I’m looking after the community I grew up in, every day, in emergency situations.”

Born in San Francisco, Boaz moved to Galilee Harbor (then Napa Street Pier) when he was 4. He and his father lived in deep water on a 30-foot Chris-Craft. Boaz was 13 before they had electricity; twice, candles ignited fires in their home.

“The neighbors were so important,” he said, recalling the way they helped each other in emergencies. His father often hosted dock barbecues, and everyone would hang out together. “Everyone became family.”

It wasn’t easy, however. “Some people lived on nothing,” he said. “That was something I didn’t want for myself.” Boaz admired his father, who told him, “if you work hard, you won’t get left behind.” He worked alongside his father, a talented woodworker, building many houses and restaurants in Sausalito.

Boaz grew up boating, discovering an aptitude for mechanics and problem-solving. If his outboard broke down, he’d paddle over to the yard, find a nail and use it as a shear pin. For a time, he worked as a jib trimmer, racing other people’s sailboats. He brings his experience to his Chris-Craft dealership at Clipper Yacht Harbor as well as his position as one of the drivers and instructors of the fireboat.

From a young age, Boaz was aware of the way the “hill people” of Sausalito perceived the “boat people.” It was especially hard when he’d visit friends who lived in houses with hot water and modern appliances. “We were jealous of them,” he said. “They’d open up their freezer and microwave a snack after school.”

“I’m a hill person now,” he acknowledged. “I have a washer and dryer.”

Hard work made it possible. For many people, Sausalito is unaffordable, which saddens Boaz. “A lot of the (waterfront) people have been priced out,” he said. “They moved further and further, and they can’t come back.”

Kaitlyn Gallagher

Kaitlyn Gutmann Gallagher is the teacher she is today because of her childhood and her education at Martin Luther King School in Marin City. “I have a really open mind,” she said. “I know there are more ways to be and more choices for human experience.”

An English teacher at San Domenico School, Gallagher grew up on Gate Six on The Camel. The 8x8x16 space had no walls or rooms for their family of four. “When I went to college it felt weird to close the doors!”

The waterfront children were often shooed outside. “It was very, very free — and dangerous and beautiful and scary,” she said. “It was like Burning Man. ‘OMG that’s so beautiful,’ and then, to your right, ‘That’s not OK.’”

She learned early to be wary of her environment — everything from storms to dogs that would bite and dudes to keep your distance from. She said, “We were street-smart in the houseboat way.”

Gallagher, who is also an essayist and poet, values creativity and art, which was very much supported by the community. “I was so fortunate to have the parents I do, but other kids weren’t so lucky,” she said. “I credit my parents and my brother, as well as many other adults who cared about me. I know it could have been otherwise.”

The proximity of neighbors meant everyone was connected. “Living the way we did didn’t allow for much arrogance or superficiality,” she said. “I miss how real we were with each other.”

What she doesn’t miss is the stress of wintertime. “We’d get blown around, all hands on deck, crashing into other boats,” she remembered. When she moved to a fixer-upper home in Fairfax, newly pregnant, her husband wondered why she wasn’t worried. “I told him, ‘It’s not going to sink!’”

Reason Bradley

Reason Bradley, owner of Universal Sonar Mount, is a self-taught welder and maker. He credits his waterfront childhood for creative freedom and, crucially, access to raw material.

“We had limitless amounts of wood and nails, and there wasn’t any regulation,” he said. “We’d build bicycle jumps, scavenge up some material and build something cool.”

Bradley’s first home was in the Arques shipyard on Gate Three, behind Mollie Stone’s Market. Then, around age 11, his mother and three siblings moved to the Gates Co-op. “The Co-op was pretty wild,” he recalled. “Walking on dilapidated old piers where you can see the nails and the structure underneath, you learn how to not fall in the bay.”

The hazards of boat living were tempered by caring adults. “People on the hill thought we were feral and wild,” he said. “We didn’t know any different; that’s how we were raised. Everyone had eyes on you.” His family lived on the first concrete barge built, which his sister Maude still lives on.

At a young age, he worked beside his godfather Peter Lamb, a shipwright, and with boatbuilder Jon Bielinski. “He took me under his wing,” Bradley said. “I worked on Annabelle in the Arques shipyard until I was 12, 13 years old.”

In his teens, he gravitated from wooden boatbuilding to metalworking and machining. He sailed in the Pacific Northwest, crabbed and logged in Alaska and worked on film sets. In the early 2000s, he teamed up with his friend Alexander Rose to build BattleBots for the reality TV series.

Bradley is proud to work in the Marinship. “I try to give back,” noting that he restored the iconic sea lion statue after it was knocked over in a storm. When there’s an issue in town, people say, “‘Oh, Reason can fix that, he’ll know what to do.’”

Bradley now lives in Mill Valley, in an 1890s house, with gardens and fruit trees. His ties to Sausalito remain strong. “Our shop is in Sausalito, my heart is very much in Sausalito, my community,” he said. “I don’t miss it a lot because I’m very much still here.”

Krystal Gambie

Krystal Gambie is the third child of a large and well-known family headed by Penelope and Michael “Woodstock” Haas. Artist and activist, her parents started an alternative press. Counting half siblings, the couple eventually had six children.

Gambie was born in The Down Winter, a floating home built by Ray Speck. Her sister Alissandre Haas and half-sister Melissa Pergerson, who still live on the docks, run a successful design shop, Tile Fever, on Gate Five Road. Gambie has just returned to the area after living in Baltimore. She is the owner of Waterfront Wonders, a Sausalito gift shop that pays tribute to the waterfront community with art, books and more.

What Gambie treasures from her past are the freedom and independence to make things and explore. “We built our own floats, hands covered in blisters and rust,” she said.

The kids of the waterfront roamed all over Gate Six. “We were the funky friends club, and our playground was really big,” she recalled. “We’d go under the docks and spook people who were out walking.”

When her parents broke up, Joe Tate took in Gambie, her sisters and her mother. “Everybody’s boat was leaking back then, and for him to take us in was really amazing,” she said.

She’s happy where she lives now, on Caledonia Street. “I love it, but it’s an apartment,” she said. In her childhood home, on the water, “It felt like we had more. We weren’t limited that much.” In communal space, they had chickens, goats and a garden.

“I do romanticize it a lot,” she said, noting that there were challenges. “Water was always leaking on us. There was a group of kids who were scarred.”

Still, Gambie misses the connections. “It was so open and tight-knit and available and supportive,” she said. “A lot of the community were outcasts, and that’s why they came — to find family.”

Alexander Rose

“I’m a person who loves to build things,” says Alexander Rose, an industrial designer and co-founder of the Long Now Foundation. “Growing up in a junkyard was magical. There were infinite things to build with.” He remembers making forts, minibikes, catapults and even a zipline.

Rose, who lives in Mill Valley now, was shaped by his parents’ experiences. His father, Timothy, was the first artist to rent space in the ICB Building, subletting and recruiting artists to create the studios and gallery it is today. His mother, Annette Rose, served as county supervisor. She was catalyzed by their eviction from their first houseboat. “It defined our lives. My mom wouldn’t have gotten into politics,” he said. “When you’re marched out of your house by sheriffs with a nine-month pregnant mom, it makes a huge impact.”

Since 1997, Rose has been working with computer scientists to build a monument-scale, all-mechanical 10,000-year clock. He has made winning combat robots with Reason Bradley and built large pyrotechnic displays for Burning Man.

His childhood inspired him to see the humanity in everyone. “The people that society might push aside because they don’t fit the norm have huge amounts of value,” he said. “They have a lot for us to learn from — they are interesting and amazing people.”

“It was a time when people could live in Marin, where interstitial people lived in interstitial spaces and did art and were creative,” he said. The changes in the waterfront don’t make him happy. “Anybody who didn’t buy anything got pushed out. That’s the saddest part.”

The waterfront children remain close, aware that they were seen as misfits. “From the outside it looked scary, but everyone was our friend,” he recalled. “There was no door we couldn’t go through in that community.”

“We were mixing with the intelligentsia and the weirdos,” he added. “I don’t know if there is another place in the world like that.”

* * *

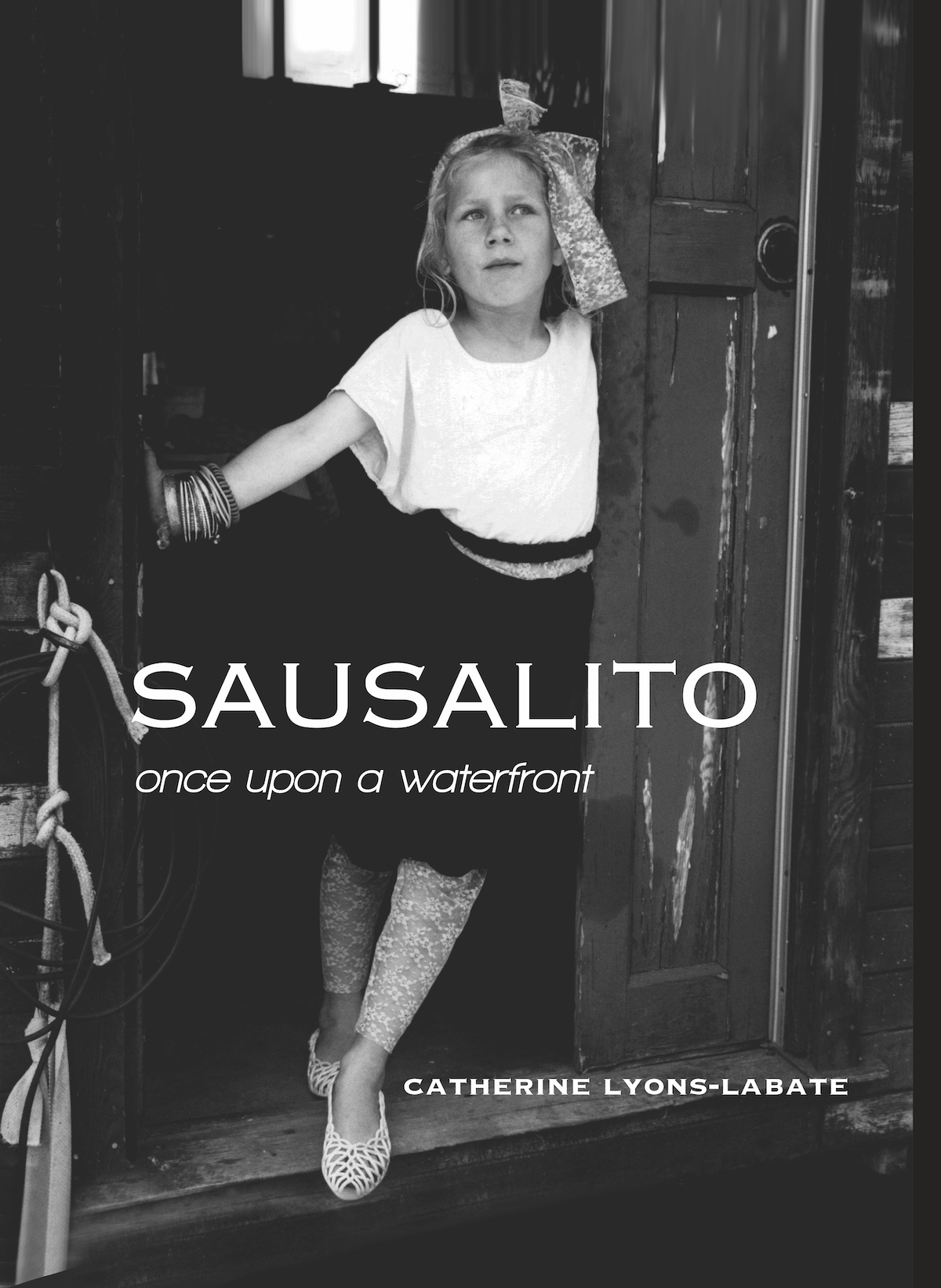

Jennifer Gennari is a children’s book author and editor. She has lived on the docks since 2010. Learn more jengennari.com. Unless otherwise noted, all photographs are from the book Sausalito: Once Upon a Waterfront, written by Catherine Lyons-Labate with her original photos. Once Upon a Waterfront contains over 180 photographs, dating from 1983–2005, of the Sausalito Gate Co-operative and stories from the people who lived there.