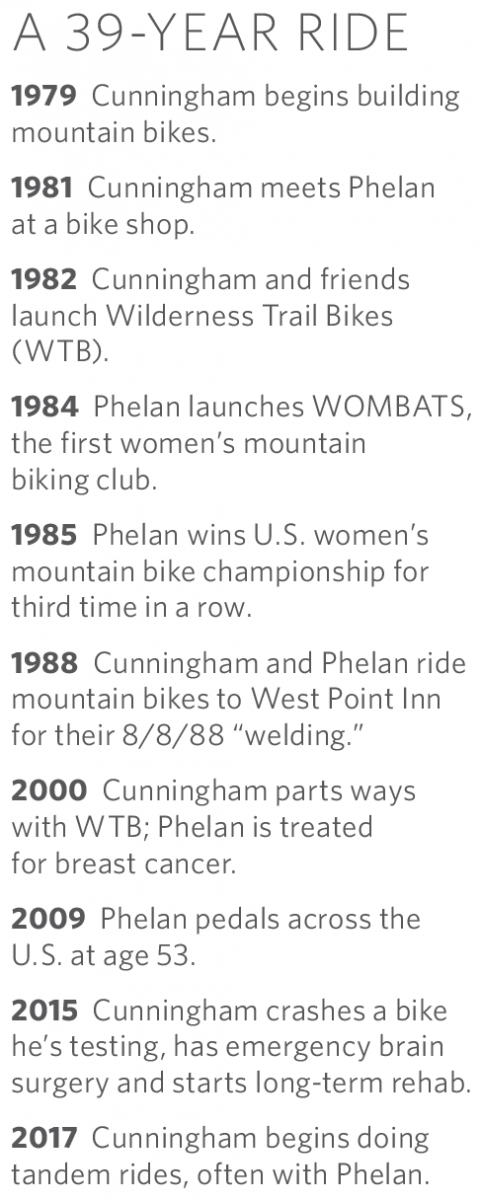

TWO CATACLYSMIC EVENTS forever changed mountain-bike pioneer Charlie Cunningham’s life. The first was the day in 1981 when Jacquie Phelan crashed into his world with the force of a mountain biker hitting pavement. The second was the day that metaphor became real — when he crashed on a solo ride in 2015. Phelan and a bevy of friends have been picking him up ever since.

TWO CATACLYSMIC EVENTS forever changed mountain-bike pioneer Charlie Cunningham’s life. The first was the day in 1981 when Jacquie Phelan crashed into his world with the force of a mountain biker hitting pavement. The second was the day that metaphor became real — when he crashed on a solo ride in 2015. Phelan and a bevy of friends have been picking him up ever since.

Cunningham, 69, has fond memories of the first “crash,” when he met Phelan in the bike shop co-owned by her then-boyfriend Gary Fisher. He has no memory of the second crash.

In the intervening years, between the pairing of this dynamic duo and the despairing fall that changed everything, the couple endured a Pacific Crest Trail’s worth of highs and lows. A high point was the weekend in 1988 when Phelan oversaw Marin’s first mountain bike festival and then married Cunningham outside West Point Inn.

“The festival was partly an excuse to have a lot of leftover beer and wine for the wedding the next day,” she says with her trademark mischievous grin. By then, they were the first couple of mountain biking: Phelan known for her flamboyance (often competing in wild costumes) and Cunningham for his bike-building brilliance (both are in the first group of Mountain Bike Hall of Fame inductees).

“The festival was partly an excuse to have a lot of leftover beer and wine for the wedding the next day,” she says with her trademark mischievous grin. By then, they were the first couple of mountain biking: Phelan known for her flamboyance (often competing in wild costumes) and Cunningham for his bike-building brilliance (both are in the first group of Mountain Bike Hall of Fame inductees).

Cunningham, a UC Berkeley aeronautical engineering student turned mountain bike fanatic, was a pioneering figure in early bike design. Road bikes and cruisers were ill-suited to trail riding, so he introduced welded aluminum frames, sloping top tubes, single chain-rings, roller-cam brakes and other key innovations. “I was driven by wanting to create bikes that worked best for me and fortunately they also worked well for everybody else,” he says.

Phelan kept busy going undefeated among U.S. women in her first five years of racing and in her activities as founder of the first women’s mountain biking club in 1984 (WOMBATS), which grew to 800 members nationwide.

The couple’s lows converged in 2000 when, in a messy settlement, Cunningham ended his connection with Wilderness Trail Bikes, the company he co-founded, and Phelan was treated for breast cancer.

Eventually they got back in the saddle, as Cunningham became a freelance inventor and custom bike builder and Phelan got healthy enough to resume leading mountain-bike camps and even pedaled across America. By 2015 they were metaphorically cruising on a smooth fire road like the one that starts shouting distance from the treehouse where they sleep each night, elevated behind the ramshackle house they call Offhand Manor.

Then came the crash. One moment, Cunningham was flying down Fairfax-Bolinas Road near their Fairfax home, testing out a road bike he’d just built for Phelan, and the next he was flagging down a ride, his body as broken as his cracked helmet. The cause of the fall remains a mystery — perhaps he was struck by a deer or hit by a driver. He spent three days in the hospital with a head injury, broken ribs, and a broken clavicle and pubic bone. “Oddly, his bike was fine,” says Phelan, “but his life and his wife were shattered.”

Then came the crash. One moment, Cunningham was flying down Fairfax-Bolinas Road near their Fairfax home, testing out a road bike he’d just built for Phelan, and the next he was flagging down a ride, his body as broken as his cracked helmet. The cause of the fall remains a mystery — perhaps he was struck by a deer or hit by a driver. He spent three days in the hospital with a head injury, broken ribs, and a broken clavicle and pubic bone. “Oddly, his bike was fine,” says Phelan, “but his life and his wife were shattered.”

He couldn’t speak for a month, couldn’t walk without a cane for three months. “I had terrible headaches, but then I seemed to recover quickly,” Cunningham says. But six weeks later the headaches returned, just after Phelan had flown to Japan for the Single Speed World Championships. “I told myself, ‘I’ll get over this,’ but it was excruciating, so I finally took a taxi to the ER.” Hours later he was near death and underwent emergency surgery for a subdural hematoma (bleeding in the brain). Phelan immediately flew home and spent the next two months visiting him at the hospital during a slow recovery that will never fully end.

Challenges remain each day. “I can’t remember what I did five minutes ago,” he says, with a smile that shows he has come to terms with his impaired short-term memory. His head injury also affected his directional sense (he gets lost easily), his vision (he’s 90 percent blind and has tunnel vision) and visual processing (he can’t read anymore). Yet it’s his diminished balance and coordination, which prevent him from safely riding a bike, that bother him the most. “Mountain biking through nature was the way I relaxed and expressed my appreciation for the earth,” he says.

Remarkably, he’s attempted solo rides alongside Phelan, but after two spills he’s turned to riding a borrowed road tandem or donated mountain-bike tandem with his wife or a friend at the front. He also does two-and-a-half-hour hikes each morning on one of two memorized routes, devours books-on-tape and is driven by Phelan to appointments to try to improve his eyesight and visual processing — sessions paid for through a GoFundMe account.

“The amount of help I’ve received is mindblowing,” he says. More than $140,000 from 2,100 people has poured in, mostly from strangers who heard or read about his circumstances. For Phelan, getting breaks from her near-constant attention to Cunningham has come in the form of donations of time from many in the tight-knit mountain biking community. People stop by to make a home repair, perform bodywork, cook a dinner, or as fellow mountain-bike pioneer Joe Breeze has done, join Cunningham for a tandem ride.

“The amount of help I’ve received is mindblowing,” he says. More than $140,000 from 2,100 people has poured in, mostly from strangers who heard or read about his circumstances. For Phelan, getting breaks from her near-constant attention to Cunningham has come in the form of donations of time from many in the tight-knit mountain biking community. People stop by to make a home repair, perform bodywork, cook a dinner, or as fellow mountain-bike pioneer Joe Breeze has done, join Cunningham for a tandem ride.

“The first bike I show off when I give tours at the Marin Bicycling Museum is the 1979 aluminum mountain bike — the first one ever — that Charlie made,” Breeze says. “More than a dozen features on that bike were ahead of their time, which shows what a visionary he was. And he’s still got it. He’s still a strong cyclist on tandem rides and more conversant than ever. He’s always out to improve on his abilities and that has never changed. He’s come a long way.”

This article originally appeared in Marin Magazine’s print edition under the headline: “Charlie’s Angels.”