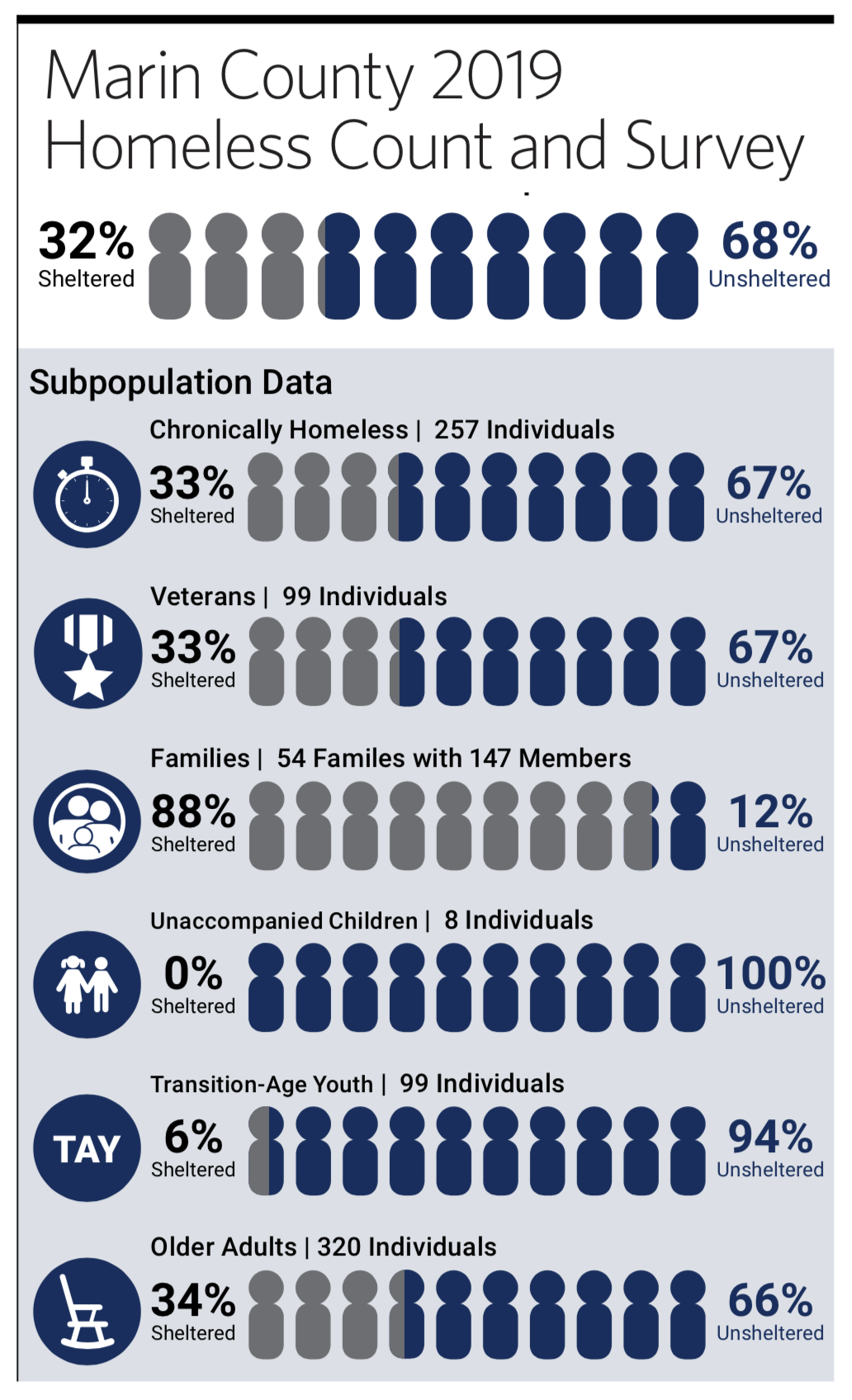

EVERY TWO YEARS at the end of January, volunteers go out into the streets early in the morning to tally the homeless in their community. This event is known as the Point-in-Time Count, and for the Bay Area overall, the 2019 results were not encouraging — San Mateo, San Francisco and Alameda counties all saw their homeless populations swell by double- digit figures, Alameda’s by an alarming 43 percent. The story in Marin was different, however. While the overall number dropped by less than 100 people, from 1,117 to 1,034 in 2019, the chronically homeless population decreased by 23 percent.

This wasn’t a lucky accident. In recent years multiple agencies around the county have shifted their approach to this pressing issue. “The problem as a whole feels impossible, but when you look at one person at a time, it becomes more doable — and we’ve housed 165 chronically homeless people in the past two years by viewing it this way,” says Christine Paquette, executive director at St. Vincent de Paul Society of Marin County.

St. Vincent provides care and services to county residents in need through its “key crisis assistance” programs, which support over 10,000 people annually. A few years ago, Paquette, who has been a part of St. Vincent management for over 14 years, noticed that it was the same homeless people moving in and out of jails and hospitals and making no positive progress in their lives. So the organization started to conduct research on ending chronic homelessness and determined that the best way to handle the issue was to house one person at a time, prioritizing the most vulnerable.

Next, in 2016, St. Vincent launched the Homeless Outreach Team (HOT) program, in which a small group of case managers build trust and relationships with the most at-risk homeless residents and help them find and maintain permanent housing. “There is no scientific way to show who will make it and who won’t,” Paquette says. “By using a vulnerability index, which is a questionnaire that addresses a host of criteria, including mental health issues, drug and alcohol abuse, who has been hospitalized in the past year and so on, we are able to create a profile and determine who is in the most need.”

St. Vincent works with other Marin County partners like Ritter Center, Buckelew Services, Marin Housing Authority, County Health and Human Services, and Homeward Bound — which is currently planning to replace its Mill Street Center with a four- story, 32,000-square-foot structure that will have 60 shelter beds and 32 permanent supportive housing units on the upper levels — as well as local cities to provide such individuals with case management, mental health services and housing vouchers. Once people are in the system, they stay in it. Nationally, the success rate for someone remaining housed by this method is 85 percent; so far in Marin it is 92 percent.

But solving this issue takes a concerted effort, and the county has a multipronged approach. In addition to espousing the approach known as Housing First, in 2017 Marin County joined a national coalition called Built for Zero. It supports participating communities in developing real-time data, optimizing local housing resources, tracking progress against monthly goals and accelerating the spread of proven strategies, all in an effort to end chronic homelessness. That same year, Marin received approval from the state of California to begin implementing the Whole Person Care Pilot, which focuses on building a coordinated, evidence based system of care for the county’s highest medical utilizers.

“Chronic homelessness is kind of like the 80/20 rule,” says Andrew Hening, San Rafael’s director of homeless planning and outreach. “It’s the small percentage of people who are most visible, causing the biggest disturbance.” In San Rafael, which is often thought of as the epicenter of homelessness in the county, using the new tactics has led to a 54 percent reduction in emergency medical services calls and an 86 percent reduction in police calls for homeless people.

“There’s been a 30 percent reduction in homelessness in San Rafael since 2017, but only 30 percent of homeless live in San Rafael, and this is where the majority of the resources are,” Hening notes. But countywide efforts are being launched, including mobile shower operations in Novato and Sausalito and eight new slips for homeless anchor-out residents in Sausalito. Statewide, a new homelessness task force created by Gov. Gavin Newsom is co-chaired by Sacramento Mayor Darrell Steinberg and Los Angeles County Supervisor Mark Ridley-Thomas.

By a conservative estimate, a chronically homeless person costs taxpayers on average about $60,000 a year, housing them brings that cost down to $30,000. Through these programs, Marin has saved an estimated $5.5 million annually. With the current efforts, the county and participating agencies are setting a goal to end chronic and military veteran homelessness by the end of 2022, one person at a time.

Kasia Pawlowska loves words. A native of Poland, Kasia moved to the States when she was seven. The San Francisco State University creative writing graduate went on to write for publications like the San Francisco Bay Guardian and KQED Arts among others prior to joining the Marin Magazine staff. Topics Kasia has covered include travel, trends, mushroom hunting, an award-winning series on social media addiction and loads of other random things. When she’s not busy blogging or researching and writing articles, she’s either at home writing postcards and reading or going to shows. Recently, Kasia has been trying to branch out and diversify, ie: use different emojis. Her quest for the perfect chip is never-ending.