IT MAY BE THE COUNTRY’S SECOND-OLDEST footrace, eight years younger than the Boston Marathon. But when it comes to natural beauty, distilled suffering, and true character(s), the Dipsea is second to none.

Begun in 1905 by members of San Francisco’s venerable Olympic Club, the 7.1-mile race from Mill Valley to Stinson Beach turns 100 this year. On the morning of June 12, 1,500 runners will do what Dipsea runners have done for a century: labor up the 676 steps near Old Mill Park, then climb some more before opening up their legs on the descent to Muir Woods. There begins the oppressive climb to Cardiac Hill, followed by a swift (ideally) downhill run to the ocean.

Roots, ruts, steps, and crowds make this event much more perilous than the average fun run. It is grueling, gorgeous, and—this is Marin, after all—a bit wacky. The Dipsea handicapping system, which awards head-start minutes based on age and gender, has resulted in winners ranging from nine-year-old girls to 70-year-old men.

To celebrate the Dipsea’s centennial, we profiled five of its legends, including 98-year-old Jack Kirk, who started in every Dipsea from 1930 to 2003. Yes, Kirk’s record is a mind-boggling feat of longevity. It is also a measure of the deep and abiding pull this race exerts on those who run it.

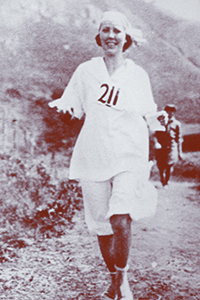

EMMA REIMANN

EMMA REIMANN

Before troglodytes in blazers decreed in 1928 that women be banned from racing distances longer than 200 meters—why, the tender creatures might swoon from the effort, might compromise their reproductive systems!—there were the Women’s Dipsea Hikes.

Separate from the men’s Dipsea races (which consistently drew fewer participants), the hikes were held from 1918 to 1922. They were groundbreaking events, possibly “the first women’s long-distance races in the United States,” according to Barry Spitz’s Dipsea: the Greatest Race (Potrero Meadow Publishing, 1993). Despite being called hikes—to elude the Amateur Athletic Association’s ban against women competing—they “were bona fide races,” says Spitz.

The greatest of the Dipsea hikers was Emma Reimann, whose father, William, ran a newsstand on Mill Valley’s Lytton Square. Runner-up in 1919 and ’20, she won the hike in 1921, getting over the course in a brisk 1:16:15. She cut four minutes utes off that time the following year, setting a course record for women that would stand for 47 years.

Reimann was denied the chance to defend her title: The hikes were discontinued after 1922. Doctors insisted that the race was too strenuous. Church groups found the attire too provocative. Such were the mores of the times, even in Marin.

In a brief article headlined “The Dipsea Amazons on the Trail,” the May 15, 1920, Mill Valley Record describes that year’s hikers as “a blithesome group” who “proved for the third straight time that girls can cover the track and enjoy it.” Indeed, a half century before the AAU got its head out of its backside and allowed women to run more than half a lap around the track, the hikers had indeed proved something: that the exclusion of their gender from distance events was based on ignorance and myth. On the eve of the Dipsea centennial, we salute Emma Reimann and her “blithesome,” pioneering ilk. They weren’t hiking. They were running their asses off.

DON PICKETT

Mr. Dipsea is 77 now, his last competitive race two years behind him. “I still jog a little bit,” says Don Pickett with a rueful smile. “I hate to even use the word jog. But I have to.”

For the second time in his life, it appears that Pickett’s running days are at an end. The first time came half a century ago. After running track his freshman year at Oregon, Pickett hung up his spikes. The new coach, Bill Bowerman, told the kid he had talent. “But I didn’t listen,” says Pickett. “It was always a regret that I stopped.”

There is a pause, and he says, “I think I made up for it.”

He moved to the Bay Area, married, and joined the Olympic Club, where he sang in the chorus and hung out in the bar. Disgusted, finally, by his advancing dissolution—“too much gin and cigarettes,” he says—he resumed running in his late thirties, on the club’s 25-laps-per-mile track. He first ran the Dipsea in 1965, finishing 71st.. Among the gifts he received for his 40th birthday, in 1968, were three extra Dipsea head-start minutes.

He won the race, but just barely, passing an 11-year-old boy 20 yards from the tape. “As I turned to comfort him,” says Pickett, “my coach from the Olympic Club shouted, ‘Let him alone!’”

Pickett’s most storied display of sportsmanship came five years later, when an Australian named Joe Patterson stopped him at a fork in the trail.

“He said, ‘Which way, mate?’” recalls Pickett, who could’ve won by sending the Aussie to the right: “He would never have known the difference, and would’ve come in a minute behind me.”

Instead, Pickett told Patterson to follow him …. and lost to the Aussie by 11 seconds.

Pickett’s Dipsea legacy transcends his ’68 victory, his nine top-ten finishes, and the four family trophies he won running with his son Toby. For years, the post-Dipsea “Survivor’s Dinner” at his Tiburon home was as much discussed as the race itself. In his jaunty white longshoreman’s hat, he became the collegial, smiling face of this race, its unofficial ambassador: Mr. Dipsea.

SHIRLEY MATSON

Shirley Matson didn’t even jog until her early thirties. It was six more years before she worked up the nerve to enter a race—a three-miler around Lake Merritt in Oakland in 1977. She came in second, and thus was born a stellar age-group running career. Matson, 64, has gone on to set a jaw-dropping 187 U.S. National Age Records (62 age group, 125 single age). In 1992, she was the nation’s top over-50 female runner, and became one of the first two distaff members of the Olympic Club, whose members immediately asked her, “Why don’t you run the Dipsea?”

She was a road racer, she explained. She didn’t do dirt. Despite her understandable qualms about venturing onto the Dipsea’s sinister terrain, she did enter, finishing second on her first try behind the defending champ, a ponytailed 10-year-old named Megan McGowan. A year later, Matson held off former Olympic marathoner Gabriele Andersen to win by 30 seconds. Matson’s subsequent victories in 2000 and ’01 made her the first woman to win three Dipseas. Then came last year.

“Nagging hip and butt pain” had kept her on the shelf in the months before the race. She let it be known, during that time, that two-time winner Melody-Anne Schultz would be the favorite. But Matson recovered from her injuries, and drew inspiration from Birdstone’s upset of Smarty Jones at the Belmont Stakes. “Even an old nag can come out of the bushes, surge to the lead, and hang on,” says Matson, who, while running nothing like a nag, did surge to the lead, then held off Schultz.

Matson crossed the finish a bit bloodied, having scraped her right knee and elbow in a headlong fall. Despite that spill, it was obvious that even if she is a road racer at heart, this four-time Dipsea winner has made the dirt her friend.

RUSS KIERNAN

Russ Kiernan ran his first Dipsea in 1970. No one who saw the craggy-faced 32-year-old huff his way to a middle-of-the-pack finish would have guessed that he would become one of the most successful runners in the history of this race. Over time, says Kiernan, now 67, his pain threshold expanded along with his knowledge of the course. “It’s mind over matter. Now, when I’m halfway up Dynamite and part of me says, ‘I can’t do it,’ another part of me says, ‘Bull—I did it last week.’”

He has since won 23 black shirts (awarded to top-35 finishers), none for a finish lower than 16th. He has won the Dipsea twice, come in second three times, and recorded an astonishing 22 top-10 finishes. A fearless descender—he is renowned for devouring Steep Ravine four steps at a time—he is also a repository of time-whittling shortcuts, and has shared, with anyone who cares to read them, a highly useful list of Dipsea time checks. (Those wishing to finish in 70 minutes, for instance, should be at the top of the steps in 8:30, and at the top of Cardiac in 48 minutes.)

He has since won 23 black shirts (awarded to top-35 finishers), none for a finish lower than 16th. He has won the Dipsea twice, come in second three times, and recorded an astonishing 22 top-10 finishes. A fearless descender—he is renowned for devouring Steep Ravine four steps at a time—he is also a repository of time-whittling shortcuts, and has shared, with anyone who cares to read them, a highly useful list of Dipsea time checks. (Those wishing to finish in 70 minutes, for instance, should be at the top of the steps in 8:30, and at the top of Cardiac in 48 minutes.)

This generosity is offset by Kiernan’s miserliness when it comes to sharing his hard-earned “alternate routes.” As he wrote in his popular “Dipsea Tips,” first published in the Tamalpa Gazette, “You’ve all been well brought up by your parents. They taught you proper etiquette: not asking people their ages or how much money they make. Dipsea shortcuts belong in the same category. It’s not proper to ask.”

He has won the race twice, and will be a favorite on June 12. “Every year, I may get 10 or 12 seconds slower,” Kiernan allows. “But every year, I gain another minute. One of these days I’m gonna be at the finish line before I start.”

JACK KIRK

It is believed to be a world record: Jack Kirk started and finished every Dipsea from 1930 to ’02. That’s 66 Dipseas (the race was canceled twice during the Great Depression and four times during World War II). The moment the streak ends is captured in The Dipsea Demon, a documentary by Drow Millar. A tottering Kirk approaches Cardiac some three and a half hours into the race. At this pace, he’s at least another two hours from finishing. Race officials offer him a ride to Stinson. He refuses at first, but eventually relents.

“There comes a time,” he says. “I think I reached that time.”

What a time it was! He finished second in his first Dipsea, and was again runner-up in ’36. Twice he ran the fastest time. But it was not until 1951 that Kirk first won the race, digging deep to hold off Paul Gentili, whom he beat by 10 seconds. He won again as a 60-year-old in 1967, surviving two falls to win by a mere five seconds.

He failed to mellow with age. Ten years ago, the then-89-year-old spent 16 days in the Mariposa County jail following a rock-throwing incident with some trespassing adolescents. Incarcerated, he simply ran laps in jail. “I told ’em the Dipsea’s coming up, you gotta train for the Dipsea,” says Kirk, now 98. “They opened my cell door, so I could run laps indoors.”

Wheelchair-bound in ’04—he broke his hip the previous winter—Kirk was Dipsea’s honorary starter. After the race, he was presented with a new trophy, the Jack Kirk “Dipsea Demon” Award for “determination, perseverance, and performance.” It is a fancy award—two-tiered, with winged creatures, ornate columns, and a golden cup. Like Kirk, it is a piece of work.

Later, a woman he did not know knelt beside him and said, “See you next year.”

Replied Kirk, “Let’s hope.”

Looks like he’s going to make it.