Eighty years ago, temporary housing was constructed in the farmland on the east side of Highway 101 to accommodate workers who had migrated from across the county to build World War II ships in the Sausalito Shipyard, and the town of Marin City was born. This summer, Marin City is celebrating its 80th anniversary with a series of events, publications, theatrical performances and exhibits that honor the rich history that makes Marin’s only majority Black community what it is today. In addition, local leaders are initiating a capital campaign to establish the Marin City Historical and Preservation Society and Marin City Museum.

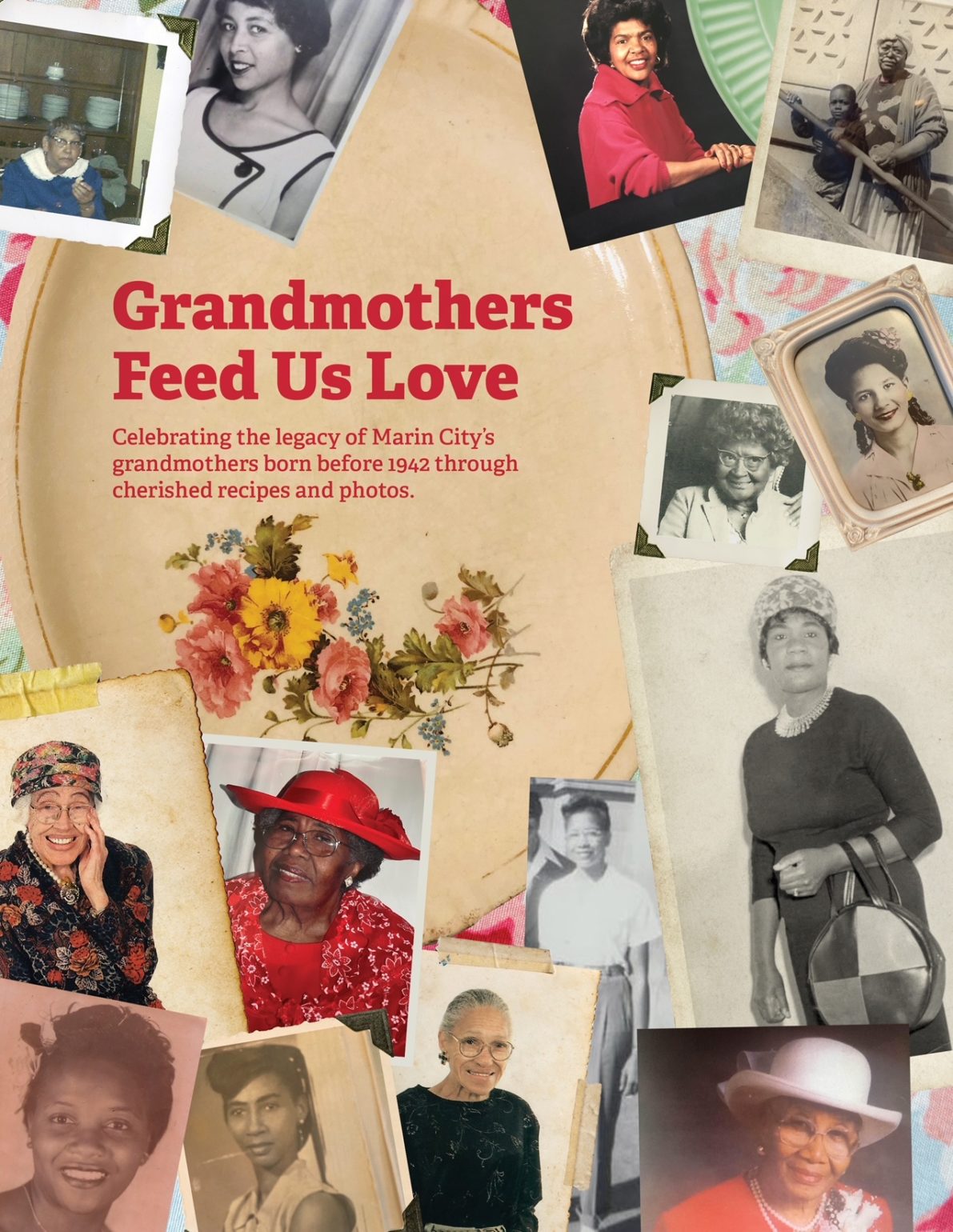

One important part of Marin City’s legacy stems from its elder women residents, known affectionately as “the grandmothers,” who arrived in Marin City in the early years, built the community’s foundation and have nurtured it for decades, according to Felecia Gaston, codirector of the #MarinCity80 celebration (in collaboration with activist and musician Jahi Torman). It’s these dedicated women who are celebrated in a keepsake cookbook entitled Grandmothers Feed Us Love: Celebrating the Legacy of Marin City’s Grandmothers Through Cherished Recipes and Photos.

“They are the dynasty of Marin City,” writes Gaston, the founder of the Marin City-based nonprofit Performing Stars and editor of the cookbook, in the forward. They are to be forever revered,” Gaston arrived in Marin City in 1989, and says she immediately felt at home because of the support of the older generation of women. “I was a single mother with two sons, and they helped me raise my sons; that’s just who these women are,” says Gaston, adding that these elders reminded her of her own Southern aunts and grandmother. “They’re survivors with true dignity and class. They were maids cleaning in white people’s homes; they took care of their husbands and children; they washed clothes; they made sure their girls and boys were properly groomed; they sewed clothes; and they made sure their children got the best education. They made the best with what they had. And, most of all, they always cooked the best soul food for their family and friends.”

Grandmothers Feed Us Love features 146 women, 25 of whom are still living, and describes in brief where each woman was born and how many children, grandchildren, and great and great-great grandchildren they have. It also includes favorite recipes from these grandmothers, an ideal metaphor for the sustenance, culinary and otherwise, they’ve provided for the community. “Their stories! If you just sat in a circle with all of these grandmothers and heard their stories, you would be amazed, and you would feel nourished,” Gaston says. “Their recipes are authentic to Black culture. So many of these women prepared food with ‘a little of this or a little of that, a pinch of this, and a pinch of that,’ tasting their food while cooking, making do with what ingredients they had at hand.” While the women in the book may not be known beyond the reaches of Marin City, their presence strengthened a close-knit community that retains its vibrancy despite the racist history that kept Marin City segregated and prevented economic growth for the town. The grandmothers’ histories offer insight into the culture that developed as many Black shipyard workers, unable to purchase homes in other parts of Marin due to redlining (racist restrictions in real estate deeds), stayed in Marin City after the war.

Eighty-seven-year-old Wyna Barron moved to the Marin City temporary housing units in 1942 when she was a young girl. Barron, who contributed her Fried Apple/Peach Pie recipe to the cookbook, was born in 1935 in Henderson, Texas. At first, her parents went ahead to Marin City to find work, and Barron stayed in Texas with her grandmother. Her mother, Vivian Barron, whose recipe for Vivian’s Booneville Apple Cake is also included in the cookbook, found a job at the Palace Hotel in San Francisco, while Wyna’s father, Theo Barron, worked for Bethlehem Steel as part of the WWII Liberty Ship building effort. Wyna was seven when her grandmother brought her from Texas to join her parents. At the time, Barron says, the community was fully integrated with many different cultures and ethnicities working in the shipyard and living in the worker housing. Barron’s grandmother, Roxie Ann Hillman, cared for her while both her parents worked, and she recalls the other elders in the community collectively looked out for the children of the neighborhood. “All the parents of that generation were working, so families took care of each other,” Barron says. “If any of the grandparents saw misbehaving children, they were always free to say something.” When the war ended, Barron’s parents, and others in their generation, didn’t want to return to the Jim Crow racism of the South. While many white shipyard workers purchased homes in nearby towns, redlining meant that Black people had to stay in Marin City or leave Marin. “There was racism in California, but it wasn’t as bad as Texas racism, so my parents stayed and fought for many years for Marin City to become a permanent community,” Barron says. In the 1960s, Barron’s parents moved into a pole home on the hillside, where Barron lives today.

Lillian Hebert, whose German Chocolate Cake recipe is featured in the cookbook, was born in Brusly, Louisiana, in 1930, and came to Marin City with her husband in 1953 looking for work. At the time, Hebert’s husband was a carpenter, and Herbert was a domestic worker. “We moved into the barracks for the shipyard workers, and we all knew each other there. We had all come from the South looking for work, and everybody was working; we were all working for something more than what we had,” Herbert says. “Marin City was a place we could always leave the doors open. The ice man would come by and put ice in our refrigerator. We would leave our doors open because there was no such thing as people robbing each other.”

Eighty-nine-year-old Anne Robinson came from a family of Italian immigrants in Youngstown, Ohio, and contributed her recipe for Pizzelles to the book. In 1955, wanting to escape what she saw as closed-minded thinking of Youngstown, Robinson joined the Air Force where she met her husband, Marin City native Glen Robinson, who passed away in 2005. At the time, the couple had to keep their interracial relationship secret. “We were afraid we’d get killed, so we kept the relationship a secret and snuck around to see each other,” Robinson says. Both Anne and Glen were stationed at the Air Force base in Hayward, so they would head off to Marin City on the weekends where Anne was warmly welcomed by Glen’s family. “We spent a lot of our time in Marin City, where Glen’s family and all of our friends were, so that was our community,” Robinson says. “I found that as much as Black people have suffered in this country, they’re still the most welcoming and loving families.”

When the Air Force found out Glen planned to marry Anne, a white woman, they sent him to Eielson Air Force base outside of Fairbanks, Alaska. “They sent Glen as far away as possible,” Robinson says. The couple moved to Eielson together and had their first child there before returning to Marin City. After renting in Marin City, they found an affordable house to buy from friends who lived in Homestead Valley, in Mill Valley, but as an interracial couple with biracial children, they were fearful about the move. “We had heard that the first Black people to move inside the city limits of Mill Valley had their home burned down,” Anne says. “Our friends who sold us the house and gave us a loan had a welcome-to-the- neighborhood party for us before we moved in so that we would know who the bigots were in the neighborhood. Three people didn’t come, and so we knew how they felt.” Anne opened a pre-school at their home in Homestead Valley, which she operated for 22 years, and Glen became a community leader, appointed by Jimmy Carter as the first Black person to head a U.S. Marshal’s office (for the Northern California region) and serving on the Marin County Board of Education for 40 years.

It’s the life stories of Marin City citizens like these three grandmothers that Gaston hopes to document and preserve. Marin City is the only Marin County town without a historical society, and a primary goal of the #MarinCity80 program this summer is to launch a capital campaign to create a Marin City Historical and Preservation Society and a Marin City Museum. Gaston sees the celebration as an opportunity to collect the documents, artifacts and memorabilia of the town’s distinct history. In addition to the cookbook, the #MarinCity80 celebration will include historical exhibits, a play and a Labor Day Weekend event.

“All the things Black people had to go through just to stay in Marin — it’s been a constant fight,” Gaston says. “But throughout that fight, people have maintained their dignity.” “The 80th celebration is more than an event; it’s the beginning of focusing on the legacy of Marin City. The cookbook is part of this — it’s our grandmothers’ legacy. They’re proud, and I’m also so proud to be the curator of this heritage book.”

To order Grandmothers Feed Us Love: Contact Felecia Gaston/Performing Stars, at 415.332.8316, email [email protected] or order through Book Passage in Corte Madera at 415.927.0960.

Vivian’s Booneville Apple Cake

From Vivian Barron

Prepare 4 cups thinly sliced apples. Add and mix in 2 cups sugar and let stand in large mixing bowl.

In separate bowl, mix:

- 2 cups flour, sifted

- 1 tsp baking powder

- 1 tsp salt

- 1½ tsp baking soda

- 1 tsp cinnamon

- ½ tsp nutmeg

Mix above ingredients into apple/sugar mixture.

Then add and mix in:

- ¾ cup vegetable oil (I use canola)

- 2 well-beaten eggs

- 1 tsp vanilla

- 1 cup each chopped walnuts (I use pecans) and raisins (cook the raisins)

Pour into large, floured pan. Bake in 350°F oven for 40 minutes. While cake is still warm, pour and spread glaze over cake.

Glaze:

Melt butter and mix with 1 cup powdered sugar, vanilla and apricot brandy.

For More From Marin:

- 31 Things to Do This August: Marin City’s 80th Anniversary, Curtain Theater Returns to the Mill Valley Amphitheater, and Outside Lands at Golden Gate Park

- How the Austin Family’s Historic Marin City Pole Home Became at the Center of a Legal Fight Against Discriminatory Housing Practices

- A Marin City Native Gives Back With STOP, a Music Therapy Program That Supports At-Risk Youth

Kirsten Jones Neff is a journalist who writes about all things North Bay, with special attention to the environment and the region’s farmers, winemakers and food artisans. She also works and teaches in school gardens. Kirsten’s poetry collection, When The House Is Quiet, was nominated for the Northern California Book Award, and three of her poems received a Pushcart nomination. She lives in Novato with her husband and three children and tries to spend as much time as possible on our local mountains, beaches and waterways. For more on her work visit KirstenJonesNeff.Com.