It started on a Friday night, May 29th, when 16-year-old Tamalpais High School student and Marin City resident Mikyla Williams decided it was time to take action. The previous Monday, George Floyd had been killed, slowly and brutally by a police officer in Minneapolis, Minnesota. As the nation watched a video of Floyd’s death, the dam broke and outrage grew; citizens across the United States had reached a tipping point with racial injustice and police brutality. That week, as people took to the streets to demand accountability for the Black lives lost to police and vigilante brutality sheltered by systemic racism, Williams watched. Although she describes herself as someone who is not normally an organizer, she knew she needed to do something in her hometown of Marin City. Her first step was to write to her longtime mentor, Marin City community leader Paul Austin. “I was watching the protests and wanted something to happen in my community, so I wrote a text, just asking Paul, is anyone organizing anything?” says Williams. “Paul said no, nothing was organized, and he put me in touch with two other women, Lynnette Egenlauf and Ayana Morgan-Woodard, and we set up a group text and started planning.” That was the seed of what would grow into a powerful 1,500 plus person protest four days later in Marin City, a historically Black community in predominantly White Marin County.

Youth in Action

Across the country young people have taken an unrelenting lead in calling for social justice. They have used their technical skills to amplify their moral authority, creating marches and protests in small suburban neighborhoods, through major city streets, around plazas and across bridges. In Marin City, Tamalpais High student Williams, Willow Creek Academy P.E. teacher Egenlauf, and Tuskegee University student Morgan-Woodard, turned to mentors and fellow community activists to support their vision. Austin, who is CEO and founder of Marin City-based nonprofit PlayMarin and a mentor to all three young women, was elemental in encouraging them to take the reins. “It was time for the youth to lead,” says Austin. “They were like, Oh, you’re not going to attach your organization to the march? And I was like, no, this is about the youth leading this, I’m just going to help you guys make sure you have what you need.”

After the three organizers connected and determined that the event would happen in Marin City on the following Tuesday, June 2nd, they got to work. “I had a rough draft outline, where and when this should happen,” says Mikyla, “And then we added to it together and created a pretty detailed plan of what we wanted to happen.” Over the weekend the team designed flyers and posted them around town and on social media. Meanwhile, Austin supported their work, making T-shirts and promoting the event through his own social media platforms and texts. He also reached out to speakers with Marin City roots, including Sekyiwa Shakur, Tupac Shakur’s sister and director of the the Tupac Amaru Shakur Foundation, Voice of the Youth founder Berry Accius and Malachia Hoover, a current PhD candidate at Stanford’s Institute for Stem Cell Biology and Regenerative Medicine.

As the event date grew nearer, word spread and momentum built, but still, the organizers had no idea how many people would show up. “I hoped it would have a good turnout, but I had never led anything before,” says Williams. “I’ve always been more of a supporter, in the audience, not a leader, so when I got to the parking lot on Tuesday and I turned around and saw so many more people still pouring in for the protest, I couldn’t believe it.”

The Day of the Event

Protesters met at the Gateway Shopping Center in Marin City. The racially-integrated crowd carried homemade signs: “Say Their Names,” “Black Lives Matter,” “Marin City Matters,” “I Can’t Breath” and “No Puedo Respirar,” among many other slogans calling for social justice. The marchers chanted “No justice, No peace,” as they walked a short distance to gather in front of the Bridge the Gap College Prep office buildings on Drake Avenue. At that point protest and community leaders spoke about police brutality, White privilege, systemic racism and getting out the vote for November. “My body is shutting down from fear and pain. From memories of our childhood. I need us, everyone, to know that we are special!” said an emotional Sekyiwa Shakur, who grew up with her brother, in Marin City. Protest leader Ayana Morgan-Woodard asked the crowd to breathe deeply and pause for a moment of silence, honoring George Floyd and so many others who have been killed by racism, including, most recently, Georgia resident Ahmed Aubrey and Kentucky resident Breonna Taylor.

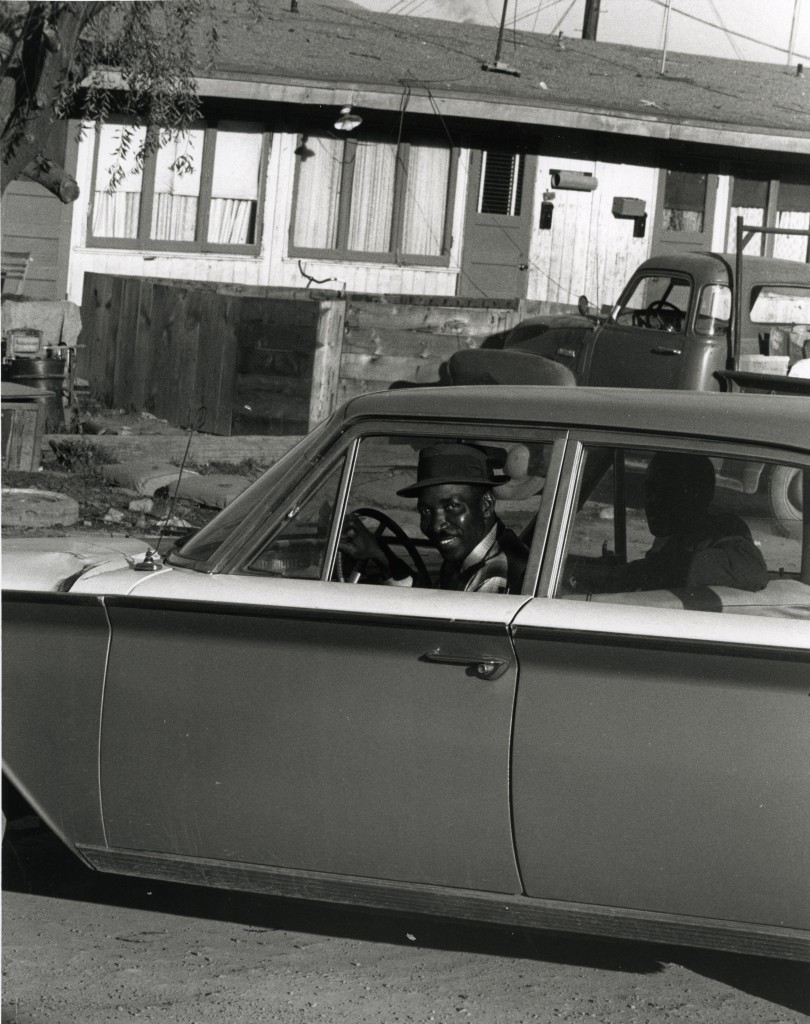

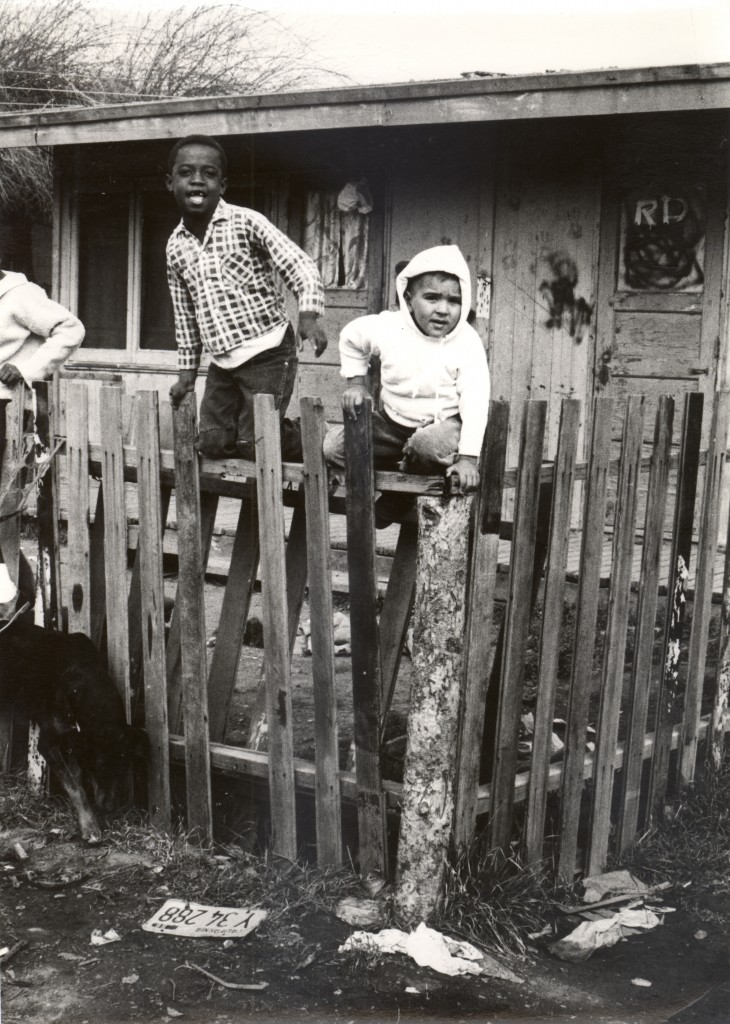

Marin’s Long History of Discrimination

In the first weeks of June, thousands of Marinites of all races have donned decorated masks, made signs and peacefully walked streets and plazas, often kneeling for 8 minutes 46 seconds, the time it took the officer kneeling on Floyd’s neck to kill him. The protests revealed a significant portion of the county’s population that is ready to take to the streets and demand changes to disrupt the foundations of systemic racism, but it would be difficult to find a Marin community that has lived with the obstacles and pain of unexamined racism, day after day, year after year, in the way the Marin City community has. The death of George Floyd struck close to home for the residents of this long-segregated city set in one of the nation’s wealthiest and whitest counties. The community, once a racially-integrated town built to house the Sausalito shipyard workers during World War II, became a primarily African-American enclave after the war when White former shipyard workers were able to purchase homes in surrounding Marin suburbs, making investments that would lead to generational wealth for their families, while discriminatory real estate covenants prevented the Black community from buying property outside of Marin City. In spite of municipal racial zoning being deemed unconstitutional in 1917, legally-enforceable covenants with racially restrictive language were put on property deeds and held up by neighborhood associations, real estate boards, and other organizations. They were outlawed in 1948, but many private parties still adhered to them until the passage of the national Fair Housing Act in 1968. Additionally, when the shipyard jobs dried up, Black workers had more difficulty finding jobs than their White counterparts due to prevalent racial prejudice. The combination led to an intractable economic disparity that persists today.

Creating Equal Opportunities for the Marin City’s Youth

PlayMarin’s CEO Paul Austin grew up in Marin City and returned to the community in 2004 to become director of the Marin City Recreation Center. As a teen at Tamalpais High School, he had thrived on sports teams, and believed that many of his social and leadership skills were developed through team activities. However, upon returning to his community he noticed that the youth of Marin City were being left behind as the surrounding privileged communities increasingly turned to expensive travel and club teams for sports and other extracurricular activities. He founded PlayMarin to close what he calls the “activities gap,” aiming to give underprivileged Marin City kids an opportunity to build on team experiences, and also offering racially integrated teams for kids of all races.

“I worked in public and in private schools in Marin County, and I just wanted Marin City kids to have some of those same opportunities, activities after school that they can take part in and to learn leadership and to be part of a team,” says Austin. “We are super segregated, here, but the rest of Marin still feels like it doesn’t affect them. Here in Marin County kids are lined up after school — they’re going to Chess Club, they’re doing drama, they’re playing sports. Kids in Marin City deserve to have the same opportunities.” One of Austin’s big pushes is for space and updated buildings for youth, and he has forged partnerships with groups such as the Warriors and basketball star and coach Jennifer Azzi’s Azzi Academy to fund and make improvements in his students’ facilities. “We have a ball field here, but it’s outdated. You can’t even play on it. It’s 20 years old, it has rocks in it, it’s uneven. If you look at every other county, everyone else has turf that kids can go play on, that feels good. We have our rec center, which is 75 years old, and there’s no room to do anything. There’s no room for a makers’ space, arts and crafts. There’s no space. Just imagine growing up in Marin City, and you are looking at everything else that sparkles in all the other communities.”

Disparity in the County

While Marin County is known as a progressive, politically liberal community, statistics about how we live tell a different story. In 2009, the U.S. Department of Housing and Development (HUD) investigated why Marin’s two largest minority populations, African-Americans and Latinos, were geographically concentrated in just two neighborhoods (Marin City and the Canal District of San Rafael, where the majority of the Latinx population lives) and these neighborhoods are the most impoverished communities in the county. Then, just two years ago, in 2019, the Sausalito-Marin City School district was investigated for violating California equal protection laws and was ordered to desegregate by the 2020-21 school year. The glaring disparities between our predominantly White communities and our communities of color — and the racist history and economic system that created and perpetuates them — are a good place for Marin County residents who would like to examine their own privilege to begin, says Austin.

Working for a Solution

For decades, Black communities across the United States have been crying out, asking Americans to recognize that racism is a problem that originates in White communities, that it is a problem we all shoulder and that it takes an active effort to fight against segregation and economic disparity. It takes self-education on the part of those with privilege and a willingness to challenge habits, to take an unfamiliar route and move outside of your own bubble. In creating Play Marin, Austin’s aim was to support the youth of his community, and also to offer Marin’s privileged mostly-White families an opportunity to more actively integrate themselves. And, he has seen the efforts of some Marin County residents in this regard: “What I started to find was a lot of parents wanting to bring their kids to Marin City because they value diversity,” he says. There is a contingency of parents from surrounding communities who come to Marin City to enroll their children in his programs, Austin says, because otherwise their children will not have an opportunity to meet kids of color or kids from different economic backgrounds.

It’s Time to Change the Systems

The national protests in the wake of George Floyd’s death have been notable for their diversity and because they have been powered by the younger generation. The Marin City protest on June 2nd exemplified this movement, and for Paul Austin, the diversity and, especially, the energy and focus of our youth, offers a reason for hope. Ayannah Green who grew up in Marin City and Corte Madera and is currently a student at Howard University spoke at the protest which she described as “a beautiful event, a huge, diverse turnout, and an opportunity to highlight our experience of being Black here in Marin.” Green’s message is that this moment is about more than just Black rights; it is time for all of us to change a system that perpetuates racism and violence against Black people. Several speakers asked protesters to educate themselves, to ask themselves to do better and do more, and to examine systems, from the national level to the local level, as they hold representatives accountable. In the words of youth activist and organizer Morgan-Woodard who was interviewed for a video about the protest: “We are here wanting to start a conversation about not only what has been done to us, but what we can do as people to come together in solidarity and to actually change the future, based on our own actions, with the help of our allies.”

This article originally appeared on Better.net.

For more on Marin:

- Juneteenth: A Brief History Lesson

- How to Keep a Positive Mindset During the Coronavirus Crisis

- Keep the Olympic Spirit Going in Marin: Join the Marin Magazine Decathlon

Kirsten Jones Neff is a journalist who writes about all things North Bay, with special attention to the environment and the region’s farmers, winemakers and food artisans. She also works and teaches in school gardens. Kirsten’s poetry collection, When The House Is Quiet, was nominated for the Northern California Book Award, and three of her poems received a Pushcart nomination. She lives in Novato with her husband and three children and tries to spend as much time as possible on our local mountains, beaches and waterways. For more on her work visit KirstenJonesNeff.com.

Kirsten Jones Neff is a journalist who writes about all things North Bay, with special attention to the environment and the region’s farmers, winemakers and food artisans. She also works and teaches in school gardens. Kirsten’s poetry collection, When The House Is Quiet, was nominated for the Northern California Book Award, and three of her poems received a Pushcart nomination. She lives in Novato with her husband and three children and tries to spend as much time as possible on our local mountains, beaches and waterways. For more on her work visit KirstenJonesNeff.com.