There are places that happen to you and places you choose. For photographer Dorothea Lange, California was both. She was 23 years old when she left her native New Jersey and arrived in San Francisco. The year was 1918 and she thought she was just passing through — instead, she stayed for the rest of her life.

The city Lange found was just a decade old, having been almost totally destroyed in the earthquake and fires of 1906. Then, as now, it was a city on the edge of the continent, a place of beauty, promise, and tragedy. Then, as now, it had little use for memory.

In the three years I spent researching and writing The Bohemians, a novel about Dorothea Lange’s early years in San Francisco, I’d traced her footsteps in the City on several occasions. I visited the site of her portrait studio at 540 Sutter Street. For a while it was a hair salon — now it stands empty. I wandered around North Beach, the favorite haunt of artists and writers in Lange’s day. Most of all I wanted to see Montgomery Block, the four-story artist’s colony that had been the beating heart of Bohemian San Francisco, but the building disappeared decades ago, one of countless places lost to development. The Transamerica Pyramid stands there now.

Every visit put more distance between my world and Lange’s. Her San Francisco was gone, and so was the feeling of that place. Not completely, but just about.

I’d already turned in The Bohemians when I thought to drive out to Steep Ravine, where I knew she’d stayed at a small cabin near Stinson Beach. Turns out I’d been looking for Dorothea Lange in the wrong places; in the end I found her in Marin, where I grew up and where I live now.

It was the son of William Kent, the Marin landowner and congressman, who built the cabins at Steep Ravine in the 1930s. Kent leased them to San Franciscans seeking an escape. They were primitive then, and they are primitive now. The cabins belong to Mount Tamalpais State Park and can be reserved for up to a week for a hundred dollars a night. There are no showers, no electricity and no heating, save for an indoor wood stove and an outdoor barbecue. Campers bring their own bedding, food, and cooking stoves — just as Lange and her family did over fifty years ago.

Her time at Steep Ravine was a kind of homecoming. She’d spent time in Marin during her early years in the Bay Area, when she was married to painter Maynard Dixon. Dixon was a fixture of Bohemian San Francisco, but increasingly he felt the pull of wilder landscapes, which he felt embodied the “real California.” Dixon and Lange took trips out to Marin in the 1920s and 1930s, which was then a collection of small towns. Later they would take their children to visit friends in Mill Valley.

Dixon and Lange divorced in 1935, but she never lost her feeling for this part of Northern California. Between 1957 and 1964, Lange and her husband Paul Schuster Taylor, a professor at U.C. Berkeley, rented one of the small, weathered cabins clustered on the edge of a rocky bluff overlooking the ocean. Sometimes their adult children came with their families; sometimes their grandchildren came out on their own.

Nineteen fifty-seven, the year she first stayed at Steep Ravine, was one year after Lange completed Death of a Valley, which documents the violent erasure of a Northern California community of Monticello. A wild horse streaking in terror across the valley, the upended earth, people uprooted and adrift — the images are an indelible act of witness. For Lange what happened at Monticello represented just one story in enormous change in the Bay Area and California. It was a disquieting reminder of the ravages brought on by modern industries. For her, the environmental damage, while searing, couldn’t be measured without accounting for the human cost, which was both a material and spiritual loss.

This is the background against which she and her family began to visit Steep Ravine. A polio survivor, she’d walked with a limp all her life. In her early sixties, she began to experience a spate of health crises. Her work had always required travel, and as her body grew more frail, it took a different turn. To photograph the “familiar,” she hung a camera on a hook in her kitchen and kept another in the living room so she’d always have one handy.

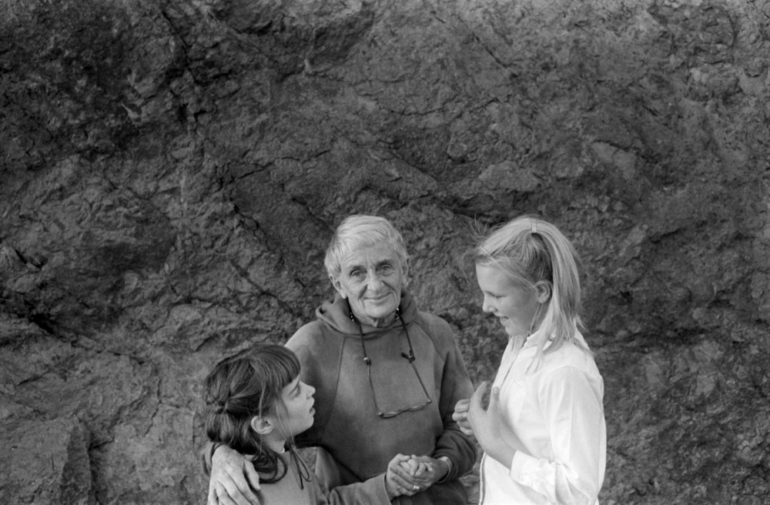

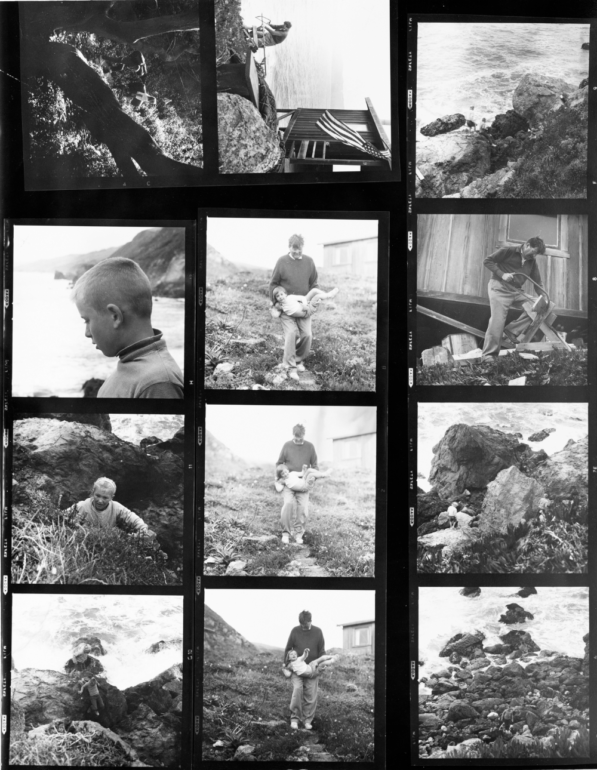

When she came out to the beach, her cameras came with her. At Steep Ravine, she could fall into the embrace of both nature and her family. Her pictures of it pulsate with the loud, messy thrill of children let loose into a raw landscape. Though physically frail, Lange’s eye was a sharp as ever. She had a particularly keen eye for distilling human emotion through gestures of the body. It’s this quality that distinguished her famous Depression-era photographs, but now she turned that eye on what was close: her family, the cabin, the beach, the sea.

Her photographs of Steep Ravine are some of the most tender and candid she ever took. To Lange, the cabin symbolized freedom, a theme she tried to capture in the more than 1,000 photographs taken during her time there. The pictures show Lange’s grandchildren cavorting in the sand, climbing boulders, and exploring the green cliffs thick with calla lilies.

“It became a special place to be together,” she wrote. “[It] made us all feel, the moment we went over the brow of that hill, a certain sense of — not peace particularly or enjoyment — [but] freedom.”

She wanted to do something with the pictures; she ran out of time. Lange died in 1965, three months before the major retrospective of her work at MOMA and before she could put together the book she planned to make with her Steep Ravine pictures. To a Cabin was published posthumously in 1973 by Margaretta K. Mitchell, a fellow photographer who’d also spent time at the cabins with her family. It is the book Mitchell imagined she might have produced.

To a Cabin is an astonishing, though little-known book. Lange rarely took self-portraits. In interviews she comes across as forthright, but fully in control. She was not a person given to self-revelation. To a Cabin, and the Steep Ravine pictures, are a kind of autobiography — the only kind of autobiography we have of her. The book includes pictures taken by her long-time collaborator, Rondal Partridge. Some of the loveliest images are the ones in which she steps away from her camera and submits herself to it. We see her with her pants rolled up at the knee, her feet bare. Always there is a camera slung around her neck.

One day this winter I drove out to Steep Ravine. I’ve been to Stinson Beach dozens of times, but this was my first trip to this part of the coast. The tide was high. Huge breakers thundered against the rocks. The fog had claimed the view, as it will do. What held me there was a sense of how far out on the edge of the world I stood. Except for the sound of the waves and wind, it was silent, and I was alone.

“Freedom, the circumstances under which people, children and their parents, and their friends, feel unlocked and free.” These are the things she sought — and found in this place.

In the stillness of a winter day, I thought about how a photograph can pull you back to a place and also back to your truest self. In that moment I could see Marin as it was a hundred years ago, when houses were few and far between. I could see it as it had been in 1964, the last year Lange had come here with her family. It was easy to image the sense of freedom she felt here. It was easy because it was the same freedom I felt. After years of searching, she’d brought me to a place as beautiful as it is timeless, a place where I could feel the shadow of something that was nearly lost but survived after all.

Dip more into the world of Dorothea Lange with Jazmine’s novel The Bohemians (April 2021), imaging the friendship between the photographer and her Chinese American assistant in 1920s San Francisco.

Dip more into the world of Dorothea Lange with Jazmine’s novel The Bohemians (April 2021), imaging the friendship between the photographer and her Chinese American assistant in 1920s San Francisco.

More from Marin:

- Looking to Get Away? Try One of These Local Work from Hotel Packages

- Sustainable Activewear from Bay Area Fashion Brands

- How to Restore, Revive and Thrive in 2021

Jasmin Darznik is a New York Times bestselling author. Her debut novel, Song of a Captive Bird, was a New York Times Book Review “Editors’ Choice” book and a Los Angeles Times bestseller. Darznik is also the author of The Good Daughter: A Memoir of My Mother’s Hidden Life. Her books have been published in seventeen countries and her essays have appeared in the New York Times, Washington Post, and Los Angeles Times, among others. Darznik was born in Iran and came to America when she was five years old. She holds an MFA in fiction from Bennington College, a J.D. from the University of California, and a Ph.D. in English from Princeton University. Now a professor of English and creative writing at California College of the Arts, she lives in the San Francisco Bay Area with her family.