YOU KNOW THAT adage about how just one person can make a difference? We’ve all heard it, and most of us have filed it in the bin of wishful thinking under the category of “Who, me?”

Not Jane Kramer. She lives it every day.

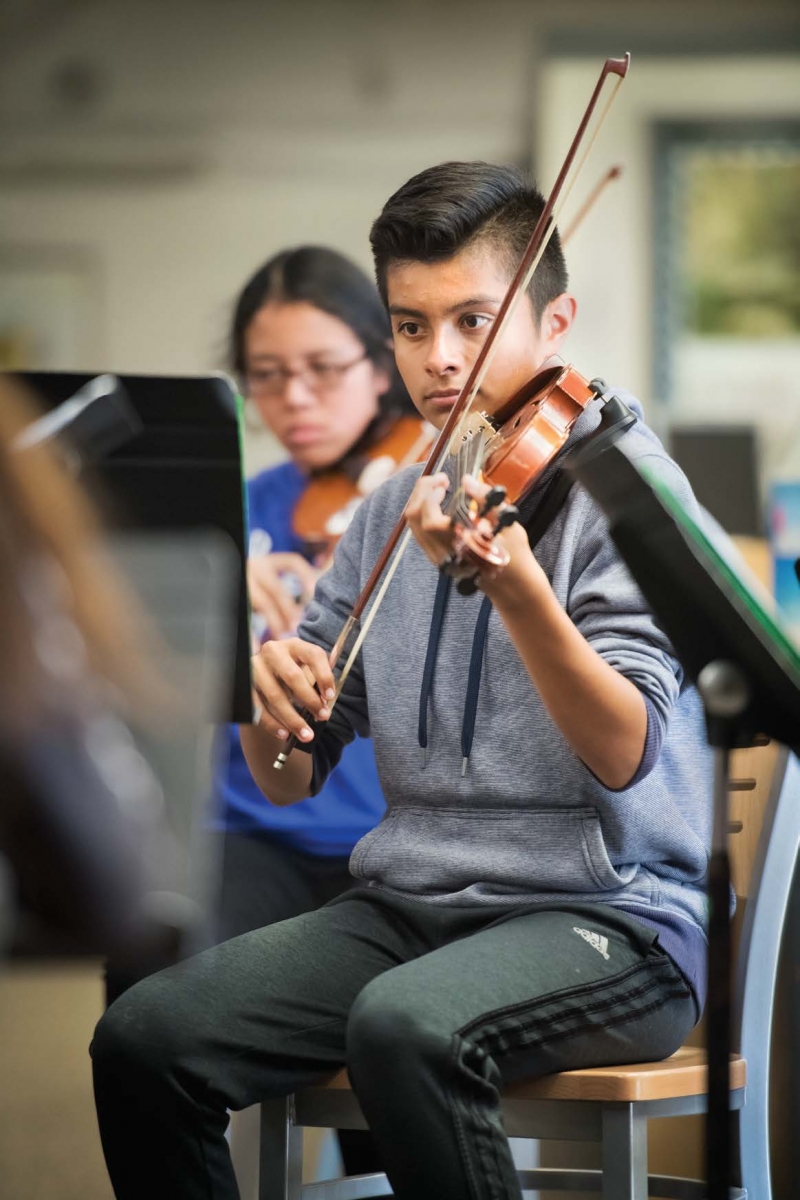

The Larkspur oboist and UC Berkeley Ph.D. is the founder of Enriching Lives Through Music (ELM), a 10-year-old nonprofit that provides free music lessons, instruments and indelible life-changing experiences to 120 children and their immigrant parents in the Canal Area of San Rafael and other Hispanic neighborhoods of Marin

ELM is the realization of Kramer’s dream to replicate the Miami music school where she came of age, the Fine Arts Conservatory, a pioneering, racially integrated program that was as much a provocateur of social change as a purveyor of lessons in the arts.

“I was 7 or 8 years old in white Miami Beach, growing up with progressive parents,” says Kramer, now 62. “And I was spending my Saturdays with black and Cuban kids. It was an amazing, formative experience for me.”

The lesson instilled in Kramer as a young woman by the conservatory’s formidable founder, Ruth Greenfield, was that for children to flourish in music — and in life — they need passion and mentorship. As an adult, Kramer saw that principle borne out when she worked in a UC San Francisco program focused on vulnerable and impoverished adolescents. “If you had a family with two sisters, for example,” she says, “why would one get pregnant and drop out of school and the other wouldn’t? What I often found was that having a passion, having something that they believed in, that they were committed to, that they felt successful at, made a difference.”

While challenging, Kramer’s work at UCSF lacked the emotional gratification music gave her. “I wasn’t passionate about it,” she says. Creating a music school in Marin addressed both issues — her need to live an emotionally compelling life and the needs of children on the margins for commitment and success.

In 2005, Kramer secured a grant from her undergraduate alma mater, Vassar College, that came with the mandate to “pursue a passion and/ or take a risk.” She took a yearlong sabbatical from her work at UCSF to devote herself “to becoming a musician again.”

“At the time, my [own] kids were pretty young. I’d wake up, I’d play my oboe all day. It was great. The truth is I don’t think I could have done ELM without [the grant]. I needed to reground myself in my passion for music before I could turn my attention to the school.”

Shortly after her leave, Kramer took the first steps toward the creation of ELM. She bought 15 plastic recorders for $5 apiece and began teaching kids at San Pedro Elementary School in San Rafael and at what was then called Pickleweed Park Community Center in the Canal.

She didn’t foresee what ELM has become — 120 students, 14 teachers; at least eight classes a week in four locations (including a new six-room space on Kerner Boulevard); a six-figure budget that pays for instruments ($800 a cello, $200–$400 a violin), transportation and salaries; and a guest conductor from the Youth Orchestra Los Angeles who leads the end-of-semester concerts.

“I didn’t think it would be what it is now,” Kramer says. “I was happier than I’d ever been just teaching music to kids who wouldn’t otherwise have had the opportunity. I didn’t have this vision for creating orchestras.”

What opened Kramer’s eyes and led to the earliest iteration of ELM as it is today happened in 2008 when she learned of El Sistema, the internationally acclaimed Venezuelan youth orchestra program created 43 years ago by economist and composer Jose Antonio Abreu, who had the idea of using classical music to improve the lives of poor children.

“When El Sistema jumped onto the international scene, I was already doing the same things,” Kramer says — seeking “social justice through music.” Suddenly, she envisioned a much grander program. “I applied to the Marin Community Foundation and got a grant to start teaching weekly violin classes.”

ELM has since grown incrementally, fueled by Kramer’s pursuit of funding (“I love writing grant proposals”) and persistence. Over the years, the program has added cellos and wind and brass instruments, recruited top-notch teachers, and moved from performing in the community center to assembling a full orchestra onstage at the Throckmorton Theatre in Mill Valley.

“One big challenge now is finding space to have the big ensemble concerts with more than 85 kids each playing an orchestral instrument,” Kramer says. “We continue to outgrow our rehearsal and concert spaces as we grow as a program.”

For her, though, the music is a means to another end. “The deeper purpose for ELM — and something I care about the most — is to give our children choices in their lives,” she says. “That’s what it comes down to.” ELM also provides kids with “the chance to be excellent. They might not be natural musicians, but in ELM they experience success. They know that if they work hard then they can be successful.”

Kramer recognizes that most of the kids are not going to be professional musicians (although several have already performed at a national level). ELM must be about “more than the music,” she says. “They say El Sistema is primarily a social program and not a music program, a social program that uses music. I mostly believe that that’s what ELM is, too: something that produces social, emotional, psychological and intellectual benefits and the creation of community through music.”

A key element of the ELM community is the parents, who invest themselves in the program by cooking for the students, raising money and learning alongside their children about music. A parent ukulele ensemble now performs with the children.

“The parent involvement means everything,” Kramer says. “One of the most important predictors of kids’ success is parents’ engagement in their lives. You can imagine with immigrant families how hard it can be sometimes — when kids are speaking a different language and are part of a different culture — for parents to stay engaged. ELM, I think, is an amazing way for parents to be engaged.”

In a video on ELM’s website, several parents talk about what ELM means to them and their families. Rosa, a mother from Mexico City whose daughter plays the cello, says she and other parents have formed their own community. “We spend time together and support each other,” she says. “We have someone to rely on in case there is a need that is outside of the music program. If one of us is going through a hard time, we have someone who will be there for us.”

Many members of the community have been moved by the positive program that Jane Kramer has created. For demonstrating that with persistence and passion one person can indeed make a difference, Kramer is being inducted this month into the Marin Women’s Hall of Fame.

“I am humbled by it,” Kramer says. “One of my mentors was a woman named Ethel Seiderman (founder in 1973 of Fairfax–San Anselmo Children’s Center). “She was just passionate about social justice for underprivileged families. She was the one who kept me going no matter what obstacle. She won this award in 1992. I feel honored to be in her footsteps.

“Truly, creating and growing ELM is my life passion. I have more energy, drive and focus than I ever have had in my life,” Kramer says. “I am doing what I believe in and what I think I can contribute my best to. It has made me brave, courageous and passionate. I feel incredibly privileged.”

In May, ELM’s end-of-the-year concert will include a tribute to composer Leonard Bernstein, who would have turned 100 this year. His daughter commissioned a special version of the song “Somewhere” from Bernstein’s West Side Story, to be played by ELM’s and other El Sistema– modeled orchestras around the world. More information is available at elmprogram.org.

This article originally appeared in Marin Magazine’s print edition under the headline: “The Right Notes”.