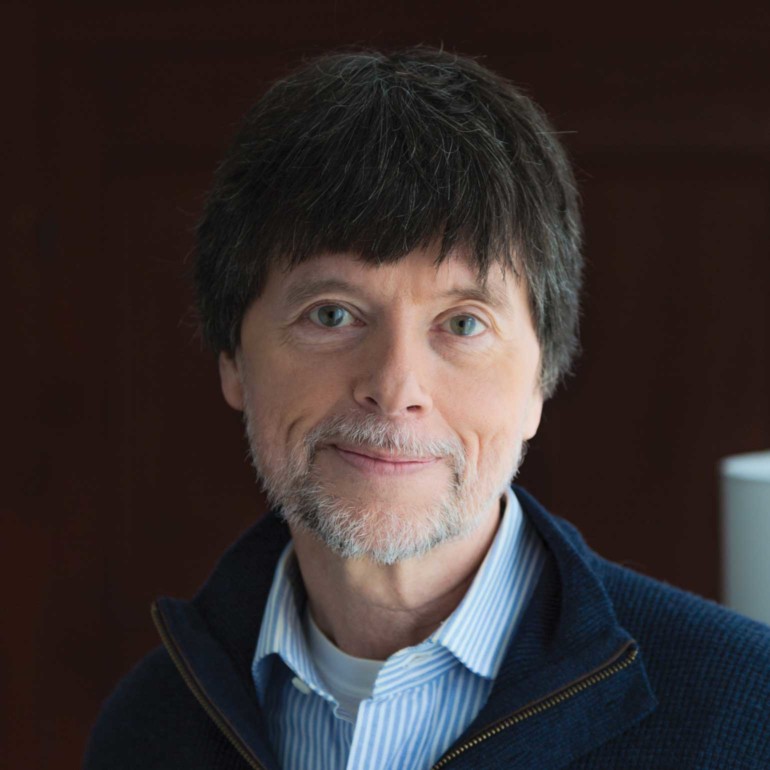

With 40 years of documentary work under his belt, filmmaker Ken Burns remains a remarkable excavator of American life. His films, including Brooklyn Bridge (1981), The Civil War (1990), Jazz (2001) and The Vietnam War (2017), have variously garnered 16 Emmy Awards, two Grammy Awards, two Oscar nominations and a Lifetime Achievement Award in September 2008 from the Academy of Television Arts & Sciences. His latest effort, Country Music, premieres September 15 on PBS. A public preview screening of the release is scheduled for July 24 in San Francisco at the Palace of Fine Arts.

1. You use a painting, “The Sources of Country Music,” by Thomas Hart Benton, which includes the myriad influences behind country music, to define the beginnings of country music. What was it about this massive, complicated American story that resonated with you?

All of the films we’ve made have, in essence, been explorations in search of answering the same question: who are we, the people called Americans? And we have also been drawn to topics that highlight some quintessentially American people or creations, from Mark Twain to Elizabeth Cady Stanton to broader topics like baseball, jazz, and the national parks (all American inventions).

Country Music combines both. It’s about a uniquely American art form and it’s filled with remarkable American characters––great artists––many of whom rose from abject poverty to follow their dreams and their talent to reach millions of people. Dolly Parton‘s parents paid the Tennessee doctor who delivered her with a sack of cornmeal. Johnny Cash‘s father was too poor to pay the Arkansas poll tax to vote. Charley Pride’s dream was that his skills in baseball or music would allow him to rise from the cotton fields of Mississippi to a better life. And so on, with many of the people whose stories we tell.

In the end, as we say, it becomes a complicated chorus of American voices, joining together to tell a complicated American story, one song at a time.

2. “The eight-part documentary was filmed over the course of eight years and was culled from 175 hours of interviews with more than 100 subjects.” How do you go about organizing such a vast amount of material and then narrow it down to a digestible format?

The process we’ve used for nearly forty years is similar to how we make maple syrup here in New Hampshire: you take 40 gallons of sap and keep boiling it down to get a gallon of syrup. We take more time than many others in collecting images and footage, in conducting interviews, and then in editing (two and half years of editing). Gathering all the extra material gives us more choices in how we ultimately tell our story. Taking that extra time provides us with the opportunity to let the story tell us what it needs to say. And the extra time allows us the chance to change our minds about how we’re telling a story, hopefully making it better.

3. How do you decide who gets left out?

This is not an encyclopedia or a laundry list of names and dates. We’re narrative storytellers who believe that biography is a vital way of telling history. And in this case, another cast of historical “characters” are songs themselves. We spend time allowing certain songs to tell their stories. For every artist whose story we tell, there are dozens of artists, songs, moments that can’t be included within our limits of time and space.

So we have to make a lot of choices and all the choices are hard choices. We realize someone else might have made different ones, but we do our best in telling the sprawling history of country music as it emerged from its diverse and tangled roots and grew and evolved over the course of the twentieth century––sprouting new branches and occasionally returning to its roots. Part of our process is to involve a number of historical advisors and experts to review the script and come to early screenings of the film-in-progress to tell us what we’ve left out or what we’ve got wrong. We take that advice into consideration as we move forward.

Loretta Lynn‘s first draft of her classic autobiographical song “Coal Miner’s Daughter,” she told us, originally had twice as many verses, so she could tell a fuller story of her life. But it was too long to fit on a record, so it had to be cut down and certain things had to be left out. We have to do the same thing.

4. You source interviews from a huge range of performers, writers, relatives, session musicians, and radio personalities but Marty Stuart appears regularly in the movie. What drew you to him as a figure that could anchor the series?

When he heard we were doing a documentary history of country music, Marty sent us a letter generously offering any help he could provide––and we’re happy that we went to him early to take him up on it. He helped us in so many ways, from suggesting storylines to pursue to making introductions to people we wanted to interview. Among country artists, he’s recognized as an unofficial historian. He’s got an amazing collection of artifacts, photos, letters and other things––enough to create his own museum––but most important, he’s been in the business since he was 13 years old; he’s heard all the stories from the music’s icons in person, and he loves to pass those stories along!

He also has a big heart and an infectious passion for country music and its relationship to the broader songbook of all American music. He and Rosanne Cash probably appear in the series more than any other people we interviewed. They have insightful things to say about the music’s early history, about certain songs and artists, and then, in the later episodes our chronological narrative catches up to their own lives and careers. There are others––Vince Gill, Kathy Mattea, Ricky Skaggs, Dwight Yoakam, Ketch Secor––who were also very helpful, beyond sitting for interviews, but it’s hard to imagine what the film would be like without Marty and Rosanne’s early and important contributions.

5. Rockabilly, hillbilly, bluegrass, mountain music, hillbilly country, are these genres all country?

One of the things we learned in this project is that country music isn’t––and never was––one style of music. It’s always been a mix. And it’s always been interacting with other styles of American music. It came from what we call “the rub” in our first episode: the intermingling of Anglo-Celtic fiddle tunes and ballads passed along in Appalachia, church hymns, work songs, minstrel songs and the blues. And as it spread in the twentieth century, by virtue of the new technology of radio and recordings, it sprouted many new branches of its own: Western swing, the singing cowboy, honky tonk, bluegrass (a syncopated version of traditional string band music), the smooth Nashville Sound, the harder-edged Bakersfield Sound, the “outlaw” music of Willie Nelson and Waylon Jennings, and so on.

In the 1950s, when so-called “hillbilly” music mixed with rhythm and blues and gospel in the swirling Mississippi River eddies around Memphis, rockabilly was born, a precursor of rock and roll. Elvis Presley, Johnny Cash, Carl Perkins and others were at the forefront. Wanda Jackson became known as the “Queen of Rockabilly” and she’s a wonderful presence in the film.

As we show over the course of the eight episodes, record companies and marketers always needed a name for the music. At first, partly out of happenstance, it was labeled as “hillbilly” music, which was sometimes used as a derogatory term––toward both the music and the people who liked it. Then it was lumped under the title “folk.” Then it was “country and western,” and then “country.” While the shifting names are an interesting story in their own right, the larger point we make is that names and narrow categorizations or stereotypes are, in a sense, meaningless or misleading. As Wanda Jackson told us in her interview: “Don’t overthink this. Just enjoy it.”

6. And cross-over nomenclature comes up again in episode 4, when Willie Nelson’s version of “Crazy” is referred to by Ray Walker of the Jordanaires as “kinda western” and Patsy Cline’s version is “country.” And Cline’s version topped the Pop charts. Does calling anyone performer’s music a certain style matter for the sake of the documentary?

As I mentioned earlier, the different names of different styles of country music––or any music––can be helpful sometimes in distinguishing them, but taken too far they can be confining. We are in the camp of the great artists who appear in our film. Willie Nelson, who was as influenced by the jazz guitarist Django Reinhardt as much as by his other musical hero Ernest Tubb, told us: “I think the lines are only imaginary and that you have to put them there because they’re not there in the beginning. It’s music.”

The great Brenda Lee talked about being called rockabilly, then rock, then pop, then country, but “when a singer is absolutely passionate about what they do, I don’t think you should pigeonhole them. Because if you ask us artists, when it’s all said and done, it’s music. That’s all it is.”

7. The Nashville sound seems to anchor the story of many of the performers, and this sound may be what many think of when they think of country. What should viewers think of as “country?

What we hope people come away from our film thinking is that country music has never been constrained and confined into one simple category. Like America itself, it’s too big for that. At its best, it takes the most basic, universal human emotions and experiences that we all share, and turns them into art. It all begins with a song. And at its best, in its wide-armed embrace, country music and its songs can remind us that we’re all in this together.

People have their own conceptions of what country music is––sometimes they think it’s something they are sure they don’t like––but based on what we’ve encountered in the screenings we’ve had of it, they learn that country music is something much broader than they imagined. And they find songs and artists they love, regardless of their preconceptions. For those who already love country music, we’ve found that there are stories and songs and characters they weren’t familiar with, and they come away wanting to hear more from a branch of country that’s new to them.

We don’t think of our films as the “final word” on any topic. We think they’re introductions to a part of American history. We hope our films inspire people to try to learn even more––by reading books, traveling to the places history was made, and in this case, listening to some great music.

8. In the episode two excerpt, Willie Nelson mentioned that he started as a promoter. How do you elicit these little nuggets from your interview subjects?

We’ve been doing interviews for our films for nearly forty years. It’s a crucial part of our process and our storytelling. What we’ve learned is that people respond best if you’re not simply marching them through a list of questions or simply looking for them to say something to fill a hole in a script. It’s not a test, it’s a conversation. You listen. You engage with them. You let them take you places you didn’t anticipate.

We had been told before the interview with Willie (on his bus, of course) that he probably would only have time for five or six questions. But once we got started, it went on for about an hour and a half. I think he enjoyed it. He had some great insights about the music, about other songwriters like Kris Kristofferson, about important moments in his life and career. Near the end, I asked him how he would like to be remembered. He said, “That he was the oldest man in the world” and laughed. Pure Willie.

9. Once you move past the first few episodes, the diversity of the clips lessens to be mostly white performers, except for Charley Pride in Episode 5. The announcer even makes mention of his first album, released without info about his race, so he will be considered only as “just another southern, white country singer.” Wynton Marsalis makes mention of this, too. Has country music become whiter over time? Is its appeal (historically) mostly to white audiences?

An important part of the history of country music is how intertwined it has been with all American music, and the influence of African Americans on many of the major artists is incredible. We didn’t “discover” it; it’s always been there, though perhaps it’s sometimes been overlooked or forgotten.

When he was out searching for songs, A.P. Carter brought along Lesley Riddle, a black slide guitarist. Carter wrote down the words and Riddle remembered the melodies to teach Sarah and Maybelle. He also taught them a gospel song from his African American church, “When the World’s on Fire,” which the Carters recorded. Then they used the same melody for a new recording, “Little Darling, Pal of Mine.” Woody Guthrie, a Carter Family fan, liked that melody, so he used it for his classic, “This Land Is Your Land.” That one story of that one melody’s journey is a wonderfully complicated American story.

Jimmie Rodgers, the “Father of Country Music,” listened to the music of the black railroad crews he served as a water boy in Mississippi; when he started recording, his songs were essentially the blues with a yodel he threw in. Bill Monroe had two musical mentors, his Uncle Pen and a black musician named Arnold Shultz, who gave him an appreciation for the blues. Hank Williams told people the only education he got in music was tagging along with Rufus “Tee Tot” Payne, an African American. Johnny Cash spent afternoons picking and singing on a porch in Memphis with Gus Cannon, who had recorded so-called “race” music in the 1920’s. Rockabilly, as I said, came about from the mix of gospel, rhythm and blues, and country music.

We tell the story of DeFord Bailey, a black harmonica player who was one of the first stars of the Grand Ole Opry in the 1920’s and 1930’s, and how when he traveled for performances in the Jim Crow South, if a restaurant refused him service, his white musician friends would leave with him and drive until they found a place where they could all eat together. And we tell the story of Charley Pride’s early career in the 1960’s–the prejudices he encountered, but also the friendship with other artists who helped him face and overcome those prejudices as his enormous talent made him a major star.

We also tell the story of Ray Charles, the great rhythm and blues star who, when he was finally given total creative control over his next album, chose to do a collection of country songs––proving that the cross-fertilization of music went in both directions across the racial divide.

As Wynton Marsalis points out a number of times in the film––as does Rhiannon Giddens and Darius Rucker––musicians of both races have always known what our culture and society too often don’t want to admit: that is the universality of music and how racially mixed it’s always been. “You take country music, you take black music,” Ray Charles said, and “you got the same goddamn thing exactly.”

10. How have your other projects, such as Jazz, influenced what you put together for Country Music?

My film on jazz obviously influenced my understanding of all American music and helped shape our approach to telling the story of songs and artists. In Jazz by the way, the critic Nat Hentoff tells the story of Charlie Parker going into a bar in Manhattan, putting a nickel in the jukebox and playing a Hank Williams song. His be-bop band mates were shocked and asked him, “Bird, why are you playing that?” Parker answered, “It’s the stories. Listen to the stories.” When we were interviewing Marty Stuart, unprompted, he recounted the same story––so it’s in both films.

But all of our previous films influence and connect with whatever new film we are doing. In Country Music‘s second episode, “Hard Times,” we describe how the music––because of the free medium of radio––actually flourished during the Great Depression. We’ve covered the Depression era in many previous films: from Baseball and Jazz and The Roosevelts to The National Parks and The Dust Bowl. With each topic, it allows us a new layer of dealing with this searing moment in history. We love the opportunity to re-encounter parts of the nation’s past from a different angle; it’s part of the discovery process that makes us feel lucky to be doing what we do.

11. Merle Haggard and Emmylou Harris are the only Californians in the press clips (and Haggard’s family hails from Oklahoma and Harris grew up around the South). Should Californians think of country music as Southern? If not, what makes the music and its history resonate outside of the South?

Merle Haggard was born in California. His parents were “Okies” and he experienced the stigma many Californians placed on the migrants from the South and Southwest, but that doesn’t mean he’s less of a native Californian. Likewise, in two episodes we tell the unforgettable story of the Maddox family, sharecroppers from Alabama who came to California (they at first thought they would walk) riding the rails in the early 1930’s, and worked their way out of poverty with their music in the Central Valley as they became known as “the most colorful hillbilly band in the world.” It’s a terrific, California story.

Buck Owens wasn’t born in California, but try to tell folks in Bakersfield that he’s not a Californian. Some people called it “Buckersfield” because he did so much to bring it into the spotlight with his “Bakersfield Sound.” Rosanne Cash was born in Memphis, but at a young age her family moved to Los Angeles and she describes her life and early career as being the product of urban Southern California. (Her breakthrough hit, “Seven Year Ache,” she explains in the film, arose from an argument she had with her husband on Ventura Boulevard.)

Gene Autry and the singing cowboy craze was born when he started making “B” movies in Hollywood. The flashy sequined suits that so many country stars wore came from Nudie Cohn’s tailor shop in Hollywood. The Byrds, the Nitty Gritty Dirt Band, Gram Parsons, the Flying Burrito Brothers, and country rock––those have a lot of California in them. Glenn Campbell’s national television show was broadcast from California. Barbara Mandrell is a Californian. Johnny Cash redeemed his career with his live concert at Folsom Prison; he also performed at San Quentin several times, where an inmate named Merle Haggard heard him and decided maybe music would be a way for him to turn his life around.

Emmylou Harris’s self-described “conversion” to country music occurred when she came from an East Coast folk club to rehearse with Gram Parsons in California for his first solo album. After he died––in California––her landmark solo albums were all produced in California with California musicians called the Hot Band. Ricky Skaggs spent time in California as a member of Emmylou’s band; she learned some bluegrass style and he got an appreciation for electric guitars and drums. The reason Dwight Yoakam came to California––where he broke through singing honky tonk songs at punk rock venues––was because, he said, that was where Emmylou Harris was making music. Dwight says, “I was born in Kentucky. I was raised in Ohio. But I grew up in California.”

I’m sure I’m overlooking some other people and stories from our film, but my point is that while many of the roots of what we now call country music undeniably originated in the American South, once it started being recorded and broadcast on the radio, the music spread and evolved across the entire nation, including California. It’s an American art form and it resonates with everyone, regardless of their region. Just ask the thousands of people who attend Hardly Strictly Bluegrass each year; I don’t believe they think they’re coming to a Southern event.

12. Why preview this project in the Bay Area?

We are doing previews of Country Music in every part of the nation, more than thirty different cities, just as we do for all of our films. PBS is the largest television network in the country, and we enjoy bringing our latest documentary to show excerpts in conjunction with local stations. The Bay area has consistently been one of the strongest regions for us in terms of interest in our continual effort to tell the story of America and its culture and its history. And I always love coming back!

13. Do you have any other connection to the Bay Area generally or Marin specifically that our readers should know about or appreciate?

I think viewers will quickly recognize the voice of my good friend Peter Coyote, who lives in the Bay Area. Peter has been narrating our films for more than a decade. He’s a remarkable person and equally extraordinary talent. He brings the narration to life, creating a wonderfully spoken voice that carries us through time. His voice is almost always present but never intrusive. It is an art.