Roughly a week after a March press conference hosted by S.F. Mayor London Breed announcing a regional shelter-in-place order, Matt Willis, Marin County’s public health officer and a Marin native, started to feel like he was coming down with some- thing. With chills and a dry cough, he went back to his San Anselmo home, took his temperature, discovered he had a fever and called his doctor. She recommended COVID-19 testing based on the possibility of exposure to the disease and his symptoms — the test came back positive.

Before the diagnosis, Willis had visited multiple hospitals and first responders and, ironically, went to the aforementioned packed press conference as part of his work responsibilities. There’s no way to know where he picked up the COVID-19 virus but, as a physician and epidemiologist, the moment he had the first few symptoms he was tested and knew it was vital that he isolated himself in an effort to keep his wife and three children safe. He knew the pandemic was on its way, he didn’t expect to be one of the county’s first cases.

Did you see the COVID-19 pandemic coming?

As soon as the reports started coming out of China about a novel respiratory virus in early January, we of course started paying very close attention. At the beginning, the news was mainly circulating in public health circles, but we were very concerned. It quickly became clear that the virus was spreading from person to person across the region, and causing serious disease, hospitalizations and deaths. From the rate this was spreading internationally, and the fact that we’re in a region with a lot of international travel, we were fully bracing ourselves and doing everything we could to prepare.

Are you working with neighboring health officials?

Yes, we have strong collaborative relationships with health officers across the Bay Area. Mainly because we share the same challenges and are essentially caring for the same larger population. The Bay Area is a single human ecosystem, especially with infectious diseases. We talk frequently, share data and work on strategy together. All are physicians and most have backgrounds in infectious diseases or epidemiology. The trust, respect and healthy debate within this small group was a huge factor in moving forward quickly as a region when the time came.

How did you stay up to date?

I wasn’t looking to the mainstream media for information as much as public health authorities. When I did look at the media it was too confusing to sift out what mattered and what was true. It’s hard to be clear headed in decision making when the information is superficial, dramatic and all over the map — from “it’s a hoax” to “it’s the end of the world.” Fortunately, the CDC (Centers for Disease Control), WHO (World Health Organization) and academic centers offer balanced and factual information. We also built systems for tracking respiratory disease and COVID-19 activity in Marin, which was really the most important information for us. It’s a fine line between seeming alarmist and sending the message that something big is coming and we need to make some radical changes in order to save lives.

Did you ever imagine you’d see so many people in Marin wearing masks?

We’ve had pandemic response plans and rehearsing them fore-shadowed what we’re seeing now. Masks, school closures, shelter in place — we’ve practiced these scenarios, but really hoped we’d never have to act on them.

How do you think you contracted it?

I don’t know. Most people get symptoms within a week of being exposed. I was doing a lot of work with our hospitals, with first responders and traveled to parts of the Bay Area that had much higher COVID-19 incidence. We also know from the testing results from our drive-through testing site that the majority of our cases in Marin during that time were people who were exposed in our community. I could have been exposed anywhere. In some ways, I’m the example of why the shelter-in-place order was so important.

What is the biggest misconception about the severity of the physical effects?

Some people have no symptoms, some have mild symptoms. But a significant number get hit with worsening respiratory symptoms in the second week, which may be a viral pneumonia. For me, and others I’ve talked with, the worst was the constant tightness in the chest and the sense that air itself irritates the lungs. What was most unexpected was how long this period of fevers and weakness lasted — about 10 days.

How did the disease progress with you?

I first felt chills and achiness that came on quickly, followed in a few hours by a dry cough. I was tested the next day and received the results a day later. I felt OK and did some work from home for a few days before it really hit. About five days in, it took a turn for the worse with more shortness of breath and way more fatigue. Even getting out of bed was a challenge. My fevers had gone away, but started spiking again. After two weeks, the first sign of recovery was that I could get up and walk without being out of breath. From there, each day was better. I was tested for immunity, and thankfully, had a strong signal on the test for the protective antibodies. I wasn’t surprised, since my system finally fought this off. So, it looks like I now have added protection for the rest of this battle.

Do you have any idea what our new normal will be, and how long shelter in place will last?

Unwinding of the shelter in place will be approached carefully and in stages. Right now, we’re learning so much about how this virus is moving through our communities, and what’s working and what isn’t. Our initial strategy has been successful, bought us time and interrupted transmission when we had been seeing uncontrolled spread. But we can’t stay locked down forever. Our health care system is now better prepared, we have more testing capacity, we know as a community how to do social distancing. We’re in a much better place to begin to relax some of the restrictions that hurt us most. The goal is to slowly build back while monitoring case counts very closely so we can adjust our approach to prevent any second surges.

What did we learn from this situation that we can carry forward?

We learned a lot about how to protect ourselves from infections — the things that used to be seen as OCD-type (obsessive-compulsive disorder) behaviors, like wiping surfaces and washing hands compulsively, are now common. I hope we all gained respect for the devastating effects of epidemics, and that this will translate into an uptake of prevention measures, including vaccinations. This has been a giant stress test for our social systems and has diagnosed some real weaknesses. Just getting back to normal isn’t the goal. The goal is building something better. I hope we learned that we need to keep public health and emergency response systems strong and well-resourced. We learned that we need to strengthen support for our elders across the board, including working to improve conditions in facilities where people live out their last years. As we build back, I hope there will be room for carefully considering what we value most — this time of doing less and consuming less has taught us something about what we really need, or don’t need as much as we thought. I hope we can keep some of the perspective we gained during this time of slower living and not rush back to a pace and patterns that are clearly less healthy.

What changes would you like to see immediately to ensure this happens?

On a policy level, we’re seeing some changes in federal and state funding and support for public health and health care, or to ensure kids who rely on free school meals can eat when schools close, but it’s framed as crisis response or emergency support. The steps we’re taking to close gaps during the crisis need to be built into new and permanent infrastructure. On a personal level, we all have a choice about our reset point, and we don’t want to waste this chance. Families have spent more time together having meals, talking and there has been less time spent driving around.

What did you miss most under quarantine?

Being in isolation in my own house, separated from my wife and kids for two weeks was really hard.

What surprised you the most on the positive and negative side?

On the positive side, I was really able to wipe the mental slate clean —I wasn’t able to read or watch TV for a lot of it. So, it was kind of like a long meditation with my only contact being my family, messages and good wishes or meals from friends and neighbors. In that sense, it was restful and renewing. On the negative side, the uncertainty about how it might turn, especially with the pneumonia, and the possibility of needing to leave my family to go into the hospital, and where that might lead, was a fear.

What did you do to care for yourself?

My team at the county is so great, and they really encouraged me to take every step to rest and recover. I cared for myself mainly by taking the time to rest and lay low. And staying hydrated.

What did you read or watch that you thought was the most helpful for you to understand your situation?

I had a lot of doctor friends sending me articles about various strategies — the take home seemed to be I just needed to rest and wait it out. It was hard to be patient and accept there wasn’t a way to fast forward through the process. It was reassuring to see the steps our local hospitals were taking — I knew they were well prepared and, if the need arose, I’d be in good hands here.

Want to hear more from Matt? Check out his recent interview about the experience on KQED’s Forum.

COVID-19 TASK FORCE

In the first week of April, the Marin Healthcare District Board of Directors declared a state of emergency and voted to commit district funds for use during the COVID-19 pandemic to ensure the health and wellness of our community. The board established a COVID-19 task force chaired by Brian Su, M.D. to assess the community’s most immediate needs. The task force recommendations will be presented to the Health Care District board throughout the year. Testing remains the highest priority, Dr. Su says. The county’s public health department, in collaboration with MarinHealth medical center (MHMC), meanwhile has already been working to thwart exposures through a mobile testing center deployed to high-risk areas. In one instance, 80 percent of residents along with staff in an assisted living center tested positive, and because of early intervention, those cases were contained. As this magazine went to press, the mobile unit, led by Drs. Elizabeth Lowe and Irene Teper, had tested 291 people, 33 of whom were positive.

The district will also be tracking costs for staffing, supplies and equipment related to all COVID-related services and will try to recoup these costs thorough FEMA. The district has limited resources and will not be able to fund all the steps the task force recommends, so any additional financial help is welcome. Marin Magazine will be updating information about these needs online throughout the year. Dr. Su provided some examples of possible candidates for district funding:

● Portable pulse oximetry kits that measure oxygen saturation in the blood of patients who have been identified as COVID-19 positive would help guide whether transfer of those patients to a hospital is needed. People who have tested positive should otherwise remain self-quarantined. As many as 10,000 kits might be needed.

● Housing for COVID-19– positive patients in hotels, dormitories or other facilities when it is not possible for those patients to self-isolate or self-quarantine because of a social or living situation.

● Mobile testing centers to test all residents and staff members of the 10 skilled nursing facilities, 50 residential care facilities for the elderly, and two behavioral health facilities in Marin. A mobile testing center consists of a van staffed by one physician, three nurse practitioners or physician assistants, testing materials, and Personal Protective Equipment. Regular repeated testing may be needed for up to a year at these facilities.

● Population antibody testing, when a reliable method is established, to help quantify regional prevalence of COVID-19.

● PPE and personnel for skilled nursing or residential care facilities where there is an outbreak and subsequent staffing shortage. On-call nursing and other workers will be needed to meet this demand.

● Pop-up testing centers for areas of outbreak, including underserved communities like Marin City and San Rafael’s Canal area and the homeless.

● Contact tracing training to quickly find and reach prior contacts of a patient found to be COVID-positive. At least 50 volunteers, including 10 Spanish speakers are needed by the county public health department for this purpose, along with full-time supervision of the process by qualified nurses.

TESTING

At the end of April, Marin County was conducting 150 viral detection tests a day. Experts believe the county should work toward a goal of testing two out of every 1,000 people which equates to 500 tests daily for Marin County’s population. Testing should focus on the highest-risk populations, such as patients in skilled nursing and long-term residential care facilities, people in densely occupied residential settings, and health care providers. The county already has several testing sites, run by Marin County Public Health, Marin Health Medical Network, One Medical in San Rafael and Golden Gate Urgent Care, for symptomatic individuals or those who may have been exposed.

TELEHEALTH

Marin residents may be avoiding treatment for emergent or urgent medical issues unrelated to COVID-19 for fear of being exposed to the virus in ERs or doctors’ offices. But local emergency rooms are using universally established precautions, and almost all area physician practices now offer telehealth appointments and in-office visits when necessary. Telehealth consultation can often be just as effective as in-person visits, notes Dr. Su, so patients should feel confident they can still get safe medical care and attention if needed.

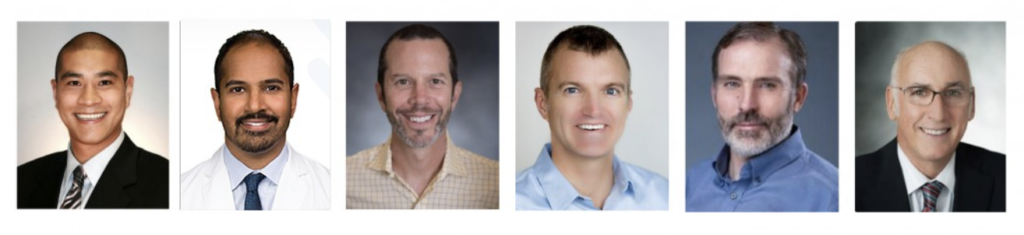

THE TASK FORCE INCLUDES:

Brian Su, M.D. Task force Chair; Director, Marin Healthcare District board and Director of Spine Surgery, MHMC

Ramo Naidu, M.D.

Director of Pain Management, MHMC

Jason Ruben, M.D. MHMC Emergency Room Chair

Gregg Tolliver, M.D., MPH prior Chief of Staff at MHMC; Chief of Infectious Disease at MHMC

Matt Willis, M.D., MPH Marin County Public Health Officer

Lee Domanico CEO of MHMC and Marin Healthcare District

How to Help

Here’s some ways you can help those working hard to keep us healthy during the coronavirus pandemic:

MarinHealth is accepting donations of critical supplies for our frontline care providers. Our donation site is able to accept the following items:

More from Marin:

- Home Meal Delivery Services for Bay Area Residents Sheltering in Place

- The Best Free or Low-Cost Online Courses to Take Right Now

- My So-Called Shelter-in-Place Life

Mimi Towle has been the editor of Marin Magazine for over a decade and is currently the national editorial director of Make it Better Media. She lived with her family in Sycamore Park and Strawberry and thoroughly enjoyed raising two daughters in the mayhem of Marin’s youth sports; soccer, swim, volleyball, ballet, hip hop, gymnastics and many many hours spent at Miwok Stables. Her community involvements include volunteering at her daughter’s schools, coaching soccer and volleyball (glorified snack mom), being on the board of both Richardson Bay Audubon Center and then The EACH Foundation. Currently residing on a floating home in Sausalito, she enjoys all water activity, including learning how to steer a 6-person canoe for the Tamalpais Outrigger Canoe Club. Born and raised in Hawaii, her fondness for the islands has on occasion made its way into the pages of the magazine. If you want more, she’s created a website, HawaiiIslander.com.