JANE HIRSHFIELD IS your classic poet. She writes for hours in solitude; her poems appear regularly in The New Yorker, Atlantic Monthly and The Best American Poems series; and she loves to futz in the garden surrounding her Mill Valley cottage.

However, Jane Hirshfield doesn’t fit the dark brooding reputation of a typical poet. She’s an energetic talker who laughs often; she rides an Arabian trail horse in Mount Tamalpais State Park, doing Volunteer Mounted Patrol; and she belongs to a local book club whose members are mostly scientists. Born in New York City, Hirshfield was writing in big block letters by the age of 8: “When I grow up, I want to be a writer.” After attending both public and private schools, she joined Princeton University’s first graduating class that included women. Hirshfield, now 61, came to Marin County in 1979 to live at the Green Gulch Farm Zen Center in Muir Beach. She’s lived in Mill Valley since 1982.

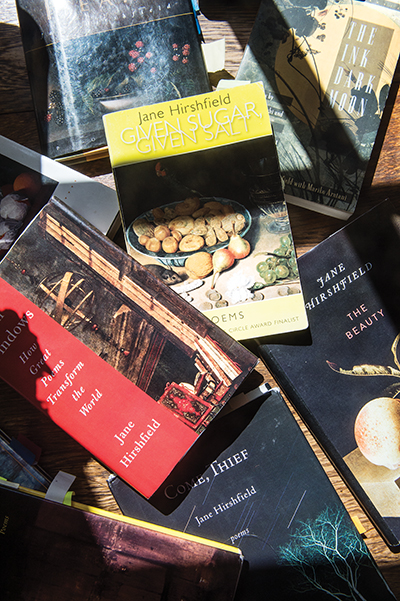

While still in college, Hirshfield had her first poem published in The Nation. Her third published poem appeared in The New Yorker and, in 1982, while she was working as a cook at Greens at Fort Mason in San Francisco, her first collection of poems was published. Six years later, Hirshfield’s poetry collection Of Gravity & Angels won the California Book Award. Since then, she’s authored seven poetry collections and two collections of essays. In March 2015, Knopf will release both The Beauty, Hirshfield’s eighth book of poems, and Ten Windows, How Great Poems Transform the World, essays she has written over the past 17 years — the first time Knopf has published two books by the same author at the same time. Hirshfield’s honors include fellowship grants from the Rockefeller and Guggenheim foundations, the National Endowment for the Arts and the Academy of American Poets — and Mill Valley’s Milley Award in the Arts.

Describe a typical day in the life of a widely published poet. Typical doesn’t really exist. This past weekend I was in Bemidji, Minnesota, at their Headwaters Poetry Festival. Soon, I’ll go to a book festival in Virginia, and then to New York for the Academy of American Poets, with whom I’m now a chancellor. My life’s closer to that of a traveling folksinger than I’d ever have imagined. I’m an introvert, I love silence and solitude — how did it happen that poetry taught me to talk with strangers and brought me to China, Japan, Poland, Lithuania, Greece, Syria, Turkey, Ireland, England and Scotland? Writing is what matters most to me — yet I spend a fair bit of my life bringing what I’ve written to people’s ears. That’s become my day job, along with some short-term teaching. Before that, I used to edit other people’s nonfiction books. Four sold over a million copies each — two by Jack Kornfield, two by Thomas Moore. Before that, I cooked, briefly drove an 18-wheel truck, did the work Zen monks do. When I’m home, though, writing is the first thing I want to do. I make a cup of coffee, turn inward and listen. I can see Mount Tam from my bedroom window. When I began writing in the morning — I haven’t always — the mountain entered a lot of my poems. Here’s a short one, from After, a book of mine that came out in 2006. The title is the capital of Lithuania, “Vilnius.”

For a long time

I keep the guidebooks out on the table.

In the morning, drinking coffee, I see the spines:

St. Petersburg, Vilnius, Vienna.

Choices pondered but not finally taken.

Behind them — sometimes behind thick fog — the mountain.

If you lived higher up on the mountain,

I find myself thinking, what you would see is

more of everything else, but not the mountain.

Let’s imagine we’re at a reading where someone says they’re unsure of the meaning of those last four lines. How would you respond? First, I’d explain where I live in relation to Mount Tam: on its hem. Then I’d ask them to think about those lines in literal terms: I can only see Mount Tam because I don’t live on it, I live below it. If I lived on Mount Tam, I’d see the bay. That’s all those lines are saying. Pretty simple. Yet when I offer this at a poetry reading, people always laugh.

Why is that? They recognize that it’s talking about the human condition, our fallibility. The poem shows that we’re always looking from some limited perspective, that whatever we see, there’s always something we can’t, because it’s behind our head, or we’re looking in the wrong place. That’s something human beings like to be reminded of. We like being kept a bit humble, if it’s done gently. The poem punctures sureness and pride. It also says something obvious you’d never think about unless it’s put in front of you — how blind we are to most things most of the time. Jokes and poems both often work like that. They let you see what you already know but always forget. That somehow delights us, the way playing peek-a-boo delights a toddler.

Do poems come to you quickly and get written quickly? Or are they the result of labored rewrites and revisions? I usually have a good sense of the full poem by the end of the first draft, but they all get some rewriting, and asked if they might be made better. “Vilnius,” the poem we just discussed, came rather quickly, and stayed fairly close to the words it arrived in. Others go through as many as 85 revisions. (I do use both sides of the paper, to respect the trees.) But it’s rare for me to struggle with a single poem for months. I can think of only one, a poem in which I was trying to find some adequate response to the 1989 Velvet Revolution in Eastern Europe. For a time it seemed as if enormous political change might occur almost entirely without violence, and yet, given the history of suffering and bloodshed in those countries, simple happiness seemed an insufficient and superficial response. My unease proved prescient — later came the enormous horror of Bosnia.

Please talk more about how you begin to write a poem. Sometimes poems come of what feels like their own accord — a line begins to say itself in my ear, I listen, I write, another line arrives. Other times, I’m shaken in some way, by an event in my life or the larger world’s life, by a thought, a fear, a grief. Finding a poem is what lets me find a way through what feels like an impenetrable thicket. Poems are answers to the questions that can’t be answered.

For someone missing the poetry gene, what can be done to appreciate poetry? It helps if you enter a poem with your ears and your heart, not just your mind. The text on the page, the shape of the lines, is a score for conducting inside yourself a piece of experience that needs your voice, your life’s own experience and knowledge and response, to be played. Poems hover between inner and outer worlds. They’re messages holding the kinds of thinking and feeling we’re often too shy to speak aloud. The most powerful moments of our lives cry out for the deepening and acknowledgment that hard-to-find words can bring them. Poems let you enter those moments more fully, and they also stop them from fading. They set the colors of your inner life the way fixatives set a dye, and they enlarge the range of what you can see and feel. One more thing is important: if a poem doesn’t speak to you, set it aside. Find one that does. No one will like all poems any more than one person will like all pieces of music.

Speaking of music, are song lyrics often considered poetry? Absolutely. Leonard Cohen’s lyrics, Bob Dylan’s, the Grateful Dead’s, have all been published as poetry. The kind of poem I write is called lyric poetry — originally, all poems were sung to some strummed lyre, or koto, or drum.

Looking back on your life, was there a poem or a book of poems that strongly affected you? The first book I bought as a young girl was a book of Japanese haiku, one of those small, one dollar books from Peter Pauper Press. In fifth grade, I fell in love with Walter de la Mare’s “The Listeners.” It’s a marvelous evocation of the mysterious life all around us, the life we can’t ever know but feel is there. That poem raised in me a sense of vastness I still turn to poems to find.

Regarding the future, is technology threatening poetry? I’m not worried. As long as poetry is read at weddings and funerals, poetry is fine. When young people fall in love and write poetry to one another, poetry is fine. In our darkest moments, poetry still is what tells us we’re not alone. Over 10 years ago, a poem of mine appeared in The New Yorker — which has a circulation of around a million readers. I still get letters about it. One came from a woman who found the poem on her late mother’s refrigerator door and read it at her memorial service. And there are ways that technology helps keep poetry alive. Technology’s a stamp, not a rival letter. One line I wrote has been tweeted all over the world, mostly it seems by young people, and it just keeps going. It’s a line I’d never have guessed would have a life of its own, “How fragile we are between the few good moments.” I’ve tried to imagine what note it strikes. I think it allows space for a person to acknowledge the harder patches of a life. If one person admits they feel fragile, others can feel less solitary in their own fears or grief. Even in happiness, poems keep us company; knowing you aren’t alone in itself helps people. It tells us our fates and blows are shared by all.