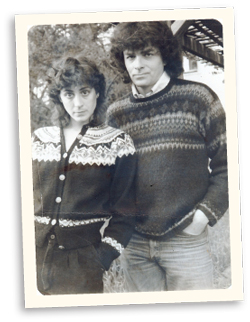

When Ellen Munger’s boyfriend and musical partner left the room for a break during a therapy session in 1983 the psychologist turned to the young girl and said, “He is going to kill you.”

But Munger didn’t listen. She remained convinced she could help Ken Ford, the musical genius 13 years her senior. “I had no idea what was going on with him,” she recalls. “He would plead with me to help him stop. He was having a nervous breakdown and the music in his head turned to voices.”

Eventually the breakdown turned into a full bipolar psychotic episode, and Munger found herself far away from the hopes and dreams she’d had as an 18-year-old Indiana singer/songwriter new to New York. Although music was still part of their life together, gone were the off-Broadway shows and rock opera material the two had been writing. In their place were a growing isolation and a constant fear. “He had seven personalities, all of which wanted to dismember me,” she says.

In what would prove to be a fortuitous move, Munger and Ford came to Oakland and rented an apartment just a few blocks from Munger’s sister. Soon came an experience so horrible, she still doesn’t remember everything. “It was 54 days of battery, torture and rape,” she says. “I was within seconds of being killed. I still can’t comprehend it.”

Munger’s sister soon realized the couple were not touring, but holed up in the apartment, and called the police. The responding officers found a cool and collected Ford, but were startled to see mad writing and drawings of Jesus all over the walls. They soon restrained him, led him out of the house in a straitjacket and put him on a 72-hour psychiatric hold.

“I wasn’t even in my body then,” Munger says of the rescue.

A New Identity

After the hold expired, Munger’s family paid to send Ford back to his hometown of Philadelphia, but he soon contacted Munger and told her he was coming to kill her. At that time, in 1983, domestic violence language was not written into the law, and it took an unprecedented court case before Ford could be committed for inpatient treatment by the California Department of Mental Health. But his commitment was only for six months.

After the hold expired, Munger’s family paid to send Ford back to his hometown of Philadelphia, but he soon contacted Munger and told her he was coming to kill her. At that time, in 1983, domestic violence language was not written into the law, and it took an unprecedented court case before Ford could be committed for inpatient treatment by the California Department of Mental Health. But his commitment was only for six months.

Finally, Munger recognized that the only way to survive was to go underground. “By then, I was putty; I was gone,” she says. “I was just doing what people told me to do.”

She was persuaded to join a pilot program of the Alameda County district attorney’s victim/witness assistance program, in its first year of operation. Before Ford could gain release, Ellen Munger had become Kathryn (the name of her grandmother) Keats (the name of her favorite poet) and disappeared from the public eye, and from the stage.

Although she no longer performed in public, she worked behind the scenes in film and in 1989 met her husband, actor Richard Conti. They married and moved to Marin a few years later and had two children.

Finally, Freedom

Then in 2005, everything changed. Ken Ford was dead, and Kathryn Keats could begin to connect her past to her present and her future: “The minute I found out Ken was dead, I did music again.”

But first, she had to tell her husband and her kids who she really was.

“I had an idea, but had never got the specifics,” Conti says. “I knew she had a traumatic past. But then she started singing and I had never seen her like that; it was amazing to watch.”

Keats released an album in 2007 called After the Silence. It was therapeutic to work on, but didn’t quite capture the sound she was after. This was when longtime friend and Marin percussionist Joe Venegoni stepped in.

“I said, ‘Come on, Kathryn, let me put a real band around you,’” recalls Venegoni, who also had been unaware of Keats’ past. “But when she did come out I was impressed with the material, the songs. The potential in them is incredible.” The band he assembled included himself and notable musicians Michael Manring on bass, Celso Alberti on drums, Jeff Oster on flugelhorn, Kelly Park on piano, Barbara Else on flute and Tom Lattanand on guitar. The band is booked to play Yoshi’s July 8, and an album featuring their mix of jazz, blues and pop is in the works.

“All these people have helped me catch up [as a vocalist],” Keats says. “You can’t know what it is like to have music back.”

Keats is also working with local producer Narada Michael Walden on a song to help launch a public awareness campaign about domestic violence and child neglect, and she’s talking with the YWCA about extending the campaign’s reach. “We need to commit to saying, ‘Let’s end this,’” she says. “We have to take the shame out of this [for the victim].”

Keats admits it’s a little strange to go from always being in hiding to the phone ringing off the hook, but she’s enjoying her new life and never turns down an opportunity to tell her story if she thinks it will help someone escape abuse. As Venegoni tells her, “You’ve lost all these creative years, but now let’s go. You can’t keep a good spirit down.”

Listen to a Track

"The In Between" by Kevin Gerzevitz