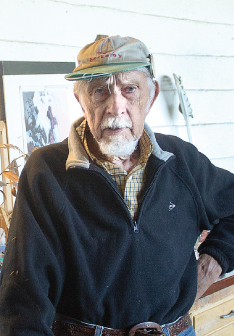

To meet Daniel Liebermann is to discover a man who at 81 still does things his own way. He lives in a home he built in the hills of Inverness, a structure he continues to add on to. The home, which is carved out of the hillside with views all the way to Mount Tamalpais, is a work in progress made from mostly recycled materials and constructed with innovative building techniques Liebermann pioneered. But doing things his own way is nothing new for the Harvard-educated architect and land planner, who in 1956 acquired an invitation to join Frank Lloyd Wright at Taliesin, Wright’s school for architects, at both the Wisconsin and Arizona campuses. For Liebermann, the experience helped launch a storied career that includes some of the most unique buildings in Marin, including the one-of-a-kind Civic Center.

What sparked your interest in architecture? In the 1930s we moved from a Princeton, New Jersey, suburb to a Dutch farm that had been added to and grown upon for 300 years and had grounds that were at one time remodeled by Frederick Law Olmsted. So what better experience can a 10-year-old get? I started gardening and learned much about sites, farming, landscape and architecture. I was greatly influenced by this Dutch architecture; it is the root of my architectural sensibility. Why I fell in love with it was because it was there, but these buildings were so much more deep and genuine than suburban houses. The authentic Dutch farmhouse was built not by architects or amateurs or Harvard boys but by genuine farmers who inherited the craft, handmanship and joinery and had scale and sense of place.

What brought you to Taliesin? When I went to Taliesin I had already been at Johns Hopkins, Harvard, the service and reserves, then back to Harvard and finally to the University of Colorado for an MFA in sculpture. I was bored with school; you couldn’t get your hands on anything at Harvard. So I went to Colorado to ski, mountain climb, botanize, go into nature and enjoy that altitude and do my sculpture. It was fun. I went from there to Taliesin at age 26.

I loved the place right away. I had visited before. When I left Boulder I went through Wisconsin and had an interview with Wright, who happened to be there (which was a miracle), and they accepted me. I had written two or three years earlier, and I got a letter from the secretary that there was a long waiting list. But I went and asked Wright directly, and the fact that I had come all the way from Boulder — he sort of visualized that I had come on a horse and buggy or something — impressed him. Of course, I was going from Boulder back to Princeton anyway. We had a nice chat, and I arrived at Taliesin in Scottsdale around Christmas.

I loved the place right away. I had visited before. When I left Boulder I went through Wisconsin and had an interview with Wright, who happened to be there (which was a miracle), and they accepted me. I had written two or three years earlier, and I got a letter from the secretary that there was a long waiting list. But I went and asked Wright directly, and the fact that I had come all the way from Boulder — he sort of visualized that I had come on a horse and buggy or something — impressed him. Of course, I was going from Boulder back to Princeton anyway. We had a nice chat, and I arrived at Taliesin in Scottsdale around Christmas.

What was the Taliesin experience like in the 1950s? What was it like getting to know Wright and others there? The misimpression of Wright is that he was a womanizer, but the women he went for were usually twice his size and probably twice his intellect and had their own ambition. To say that he took advantage of them is laughable. They were pretty ferocious characters who found a certain liberation in meeting a genius with a similar philosophy.

I was invited the last week I was there to stay at the school. It was announced that Wright and [his third wife] Olgivanna were coming to lunch, and that was really the high point. They came personally to have a little lunch with me and invite me to stay permanently at Taliesin, which was significant. Not that you get paid for that, but I could have lived there and I probably wouldn’t have done any architecture; I would have written — like a Walt Whitman. Being at Taliesin in Arizona gave you a perch over the whole of America at the time, with a certain wisdom, a certain perspective — what happened and what was happening — sweeping by you all in its own little eddy. Wright was born right after the Civil War; it was amazing how modern a mind he was.

It was a great time. I could have stayed at Taliesin forever.

How did you end up in Marin? My parents decided they wanted to retire, so they moved out to the Bay Area. They can be credited with getting my architecture off the ground; you might not have ever heard of me otherwise. They commissioned me — to build my very first buildings — my house and their house, the ones in Mill Valley. I bought six acres there. The waterfall in Mill Valley was part of the property, from Cascade up to Lovell. I acquired this property and put in a road to the double clay tennis court and built their house in 1960. The setting is perfect, just a dream place.

How did you end up in Marin? My parents decided they wanted to retire, so they moved out to the Bay Area. They can be credited with getting my architecture off the ground; you might not have ever heard of me otherwise. They commissioned me — to build my very first buildings — my house and their house, the ones in Mill Valley. I bought six acres there. The waterfall in Mill Valley was part of the property, from Cascade up to Lovell. I acquired this property and put in a road to the double clay tennis court and built their house in 1960. The setting is perfect, just a dream place.

And then I built the Radius House [on the same parcel] for us, my wife Eva and I, and we moved into it when Ben, our first child, was under a year old. My daughter Wanda was born there.

What was your involvement in the building of the Civic Center? After arriving in the Bay Area I was invited to join the Aaron Green office on the recommendation of [Taliesin architect] Wes Peters and Mr. and Mrs. Wright. Aaron was the only practitioner under the Wright flag who created a joint office representing Frank Lloyd Wright and himself privately. It was an unusual and unique setup, and Aaron insisted on that.

Well, Aaron was always on the run, like a politician. He had to be to put together all these disparate and conflicting interests. [Green managed the Civic Center project for Wright and saw it to completion after Wright’s death in 1959.] Marin almost stopped the thing because of the vote [the 1960 election that brought in new Marin supervisors not in favor of the project]. We were there at that time; maddening. That stupid supervisor stopped it all with a snap of the fingers and lost millions of dollars. It was the middle of the winter, and we had about 10 contractors all signed up. But in the end this pushed it forward faster. This was the first thing that happened when I joined Green, because it was in design and projection when I was at Taliesin.

I was given a lot of the grading, contours, rough fittings of the proto-buildings, parking terraces, walls and roads, off-ramps and stuff. I was already known as a contour guru, but I was really a kid. But that is what I had developed a peculiar talent for.

I was given a lot of the grading, contours, rough fittings of the proto-buildings, parking terraces, walls and roads, off-ramps and stuff. I was already known as a contour guru, but I was really a kid. But that is what I had developed a peculiar talent for.

Most people don’t get me because all my buildings look the same. I was not an art deco type; I was in pursuit of a deeper organicism. The Civic Center — I would never have designed an enclave like that. I would have taken those hills and created a large kind of geodesic canopy covering a developed interior landscape with terraces and mezzanines inside of it. But I love the Civic Center; I think it has held up well despite all the criticism. It’s a good building.

What about Aaron Green’s work on Marin City? I was involved in some of the landscaping of that on the tail end of the project. The thing about that project, which was endearing, was that Aaron was not the snob that people may have attributed to his character. He was actually, deep down, equalitarian; very American. He wanted to do his best for the workers who came mostly from Marinship — to really dedicate a serious Wright/Green–type project to the public housing project. I’ve proposed a greening up of that site; build green houses in between, green walls. Keep what is there but convert it to a more modern usage. Aaron’s fealty to doing something worthy there was a significant thing that should be talked about when talking about Aaron.

What is your architectural philosophy? I see buildings as a very dynamical static bundle of forces. The influence of boats on me is very important. All these houses are a resolution of dynamical complex stress forces: seismic, geo, uplift, slow geophysical drifting, instability, soil, winds — all of that. You don’t see it, but it is all reading off huge numbers. These buildings are like yachts, sailboats moored at anchor or at sea. The motion isn’t as visible, but the dynamical inputs are as great. So you begin to conceive of a building that way. The final dynamic is actually the neurology of the brain — how we do or do not see things by bending, manipulating and modulating shapes that we are not accustomed to, as I did in that house in Mill Valley in 1960. You begin to discover the relativity of the perception of spatial quantity; you need to break out of the box.