One morning in 1974, when rancher Joe Pozzi was 13 years old and milking cows in his family’s dairy barn alongside his father and siblings, a green station wagon bumped down the road leading to the Pozzi’s Valley Ford property in West Sonoma. There was great excitement, Pozzi says, whenever anyone ventured down that rural road, so the children watched with intrigue as their father greeted the stranger who stepped out of the car. “Here was this guy, he had big glasses, bushy hair and an old green jacket, so he looked pretty rough,” remembers Pozzi. “After talking to him for a while my dad came back into the barn and said: ‘Damn hippy wants to build a fence for us. I told him we build our own fences.’”

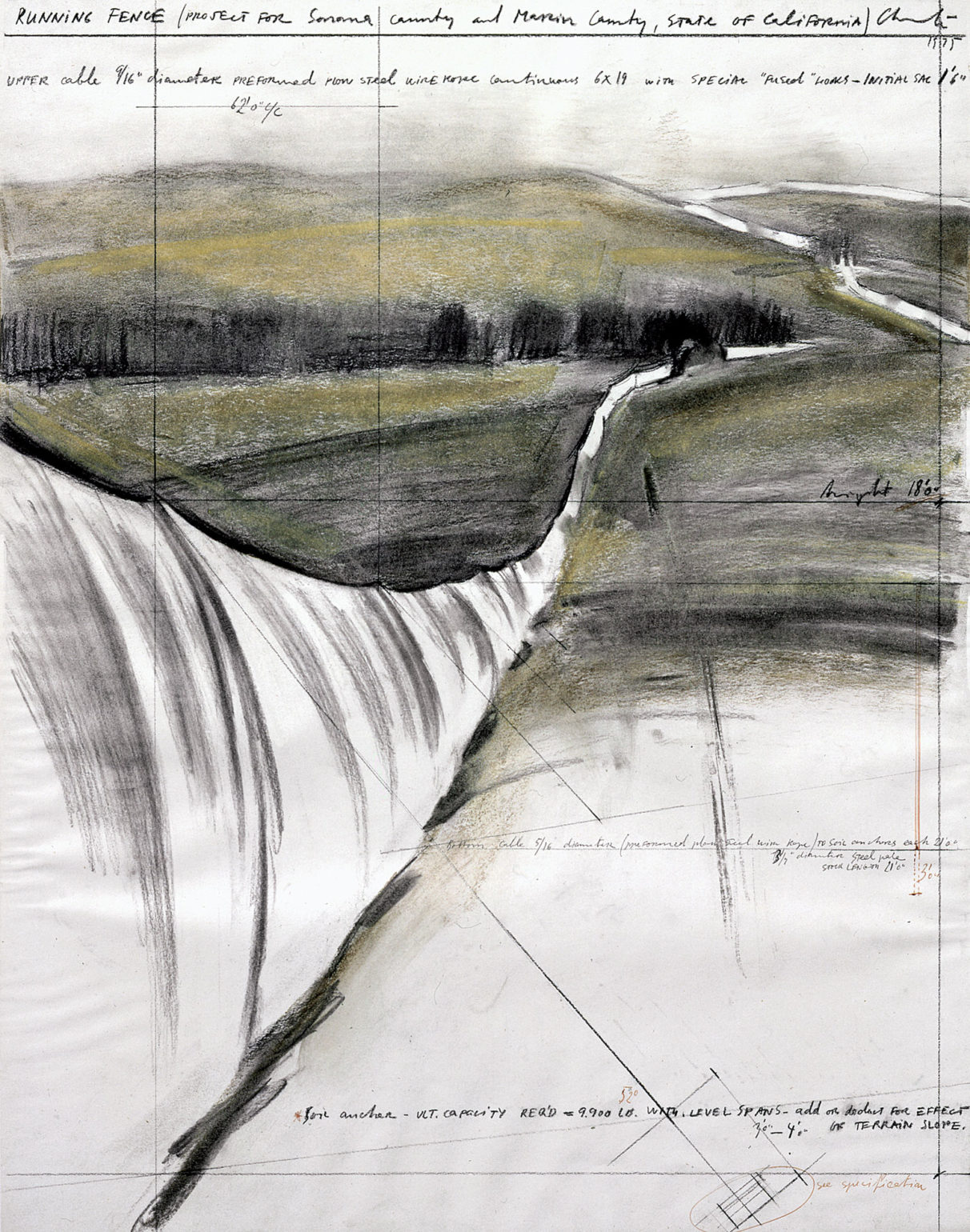

That hippy, it turns out, was renowned Bulgarian artist Christo (Christo Vladimirov Javacheff, 1935–2020), and the fence he was referring to was “Running Fence,” a “public art event” he envisioned building across the North Bay landscape. Fortunately, Pozzi’s father was kind enough to invite Christo to come back by the Pozzi ranch later, when the family was not so busy with chores, to further discuss his strange request. When Christo and his French partner and co-creator, Jeanne-Claude (1935–2009), came back that afternoon, the Italian family invited them into their home for antipasti. The eccentric artists sat with the ranch family and shared a book about a project they had completed in Colorado called “Valley Curtain,” 200 square feet of bright orange fabric draped across a high mountain pass called Rifle Gap. The Pozzi family looked through the photos in the book as Christo and Jeanne-Claude described their creative vision — a white cloth fence, almost 20 feet high and 25 miles long, meandering over the West Marin and West Sonoma hills, from the populated region along Highway 101 through semirural developments, across farmland, all the way to the Pacific coast near the town of Bodega Bay, where it would spill into the ocean.

“They were both so polite and respectful,” Pozzi says. “My parents liked them immediately and agreed then and there to let “Running Fence” cross about 2 miles of our property. That was the beginning of a great relationship, let alone a great project.” The teenage Pozzi, intrigued from the start with this duo who might as well have come from another planet, would go on to get a summer job on the project, carrying stakes for Christo and the lead engineer and head contractor as they surveyed and marked the layout of the installation.

The Pozzis were just one of the ranching families Christo and Jeanne-Claude won over as they prepared to create a temporary artwork that would exist for only two weeks. “We all thought it was goofy at first,” says Spirito Ballatore, whose family also owned a property critical to the project. “What? You’re going to build a 19-foot fence? But Christo was a straight shooter; he respected us. He was a man of his word, and my mom and dad became supporters. He very much swayed the ranchers to his side.” According to Ballatore, once his parents and other ranchers had decided that yes, the project could happen, they didn’t want the government to get involved. In hindsight, some ranchers in the West Marin and Sonoma community believe that Christo and Jeanne-Claude understood from the start that ranchers would not appreciate governmental intervention, and that they banked on the agricultural community’s support. “We laugh about it now,” Ballatore says. “They knew, no one is going to tell ranchers what they can or cannot do on their property.”

Bill Bettinelli was the president of the Petaluma Chamber of commerce and a lawyer representing the ranchers during that era. He met Christo and Jeanne-Claude in 1972 when they first arrived in the area and came to his office to ask for his support in connecting to local property owners. “They were considering three different spots along the California coast,” Bettinelli says. “They were impressed by the beauty of this area, and could imagine the whole layout done visually, through developments, over hills, around groves of trees — it was the visual impact. I told them it would never happen, that they might get government approval, but they would never get the support of the farmers and ranchers. And I was dead wrong.”

From 1972 to the early fall of 1976, when they stretched the final panel of the fence into the sea between Estero de San Antonio and Estero Americano in Bodega Bay, Christo and Jeanne-Claude faced 18 public hearings and three sessions at the Superior Courts of California. They also drafted a 450-page Environmental Impact Report. All the while, a community of unlikely art activists grew around them. “Every hearing would fill up with farmers and ranchers — the panels or boards were amazed by the group that showed up,” Bettinelli says. “It became a friendly club of about 50 people who followed them around, going to every hearing, staying late into the night. And Christo would always get a reservation at a restaurant for everyone to meet up afterward.” This community went on until Christo and Jeanne-Claude both had passed away, decades later, says Bettinelli. Jeanne-Claude, whose English was quite good, was especially open and charismatic, according to Bettinelli. She had a contagious enthusiasm and connected with families in a genuine way. The friendships became so strong that people from the ranching community, including Bettinelli himself, later traveled to attend the openings of the couple’s subsequent projects, such as “The Gates,” which was conceived in 1979 and opened in New York City’s Central Park in 2005. Christo and Jeanne-Claude also returned to the North Bay for gatherings, including Ballatore’s mother’s 98th birthday, which they attended in November of 2009, just four days before Jeanne-Claude passed away of a brain aneurysm. When Christo spoke publicly about “Running Fence,” he would reference not only the elaborate technical construction, but also the social dimensions — the surprising alignments that crossed cultural and political lines. In the minds of the artists, “Running Fence” included the unfurling of civic and community experiences over time, the entirety of the years-long permit process, the antagonism as well as the friendships formed, and the relationships that endured, like an after-image of the billowy, winding cloth fence.

When construction finally began in 1976, it took five months of nonstop industry, employing skilled labor as well as paid students and other workers to work on construction. Ballatore was 20 years old, just out of community college, when he joined the project putting up stakes and driving a service truck. Many local students joined the project because Christo and Jeanne-Claude paid them well. “Minimum wage was $1.75, and they paid me $7 an hour,” Ballatore says. “It was a good job. There was no place else where I could make that kind of money.” The estimated cost of the project was $3 million dollars, an extraordinary amount of money in the 1970s, and the artists paid for the project themselves. Christo would periodically return to New York to paint and sketch, and to sell his work to raise money for the project. In the end, the fence involved 200,000 square yards of white nylon fabric, 90 miles of steel cable, 2,050 steel poles, 350,000 hooks and 14,000 earth anchors. “It was fascinating to me as a kid, all the materials showing up, all the hustle and bustle,” Pozzi recalls. “The project was majestic, and I thought, if someone can do this, you can do anything.”

On September 10, 1976, “Running Fence” was completed, connecting the Highway 101 corridor to the Pacific Ocean, and stitching together the municipalities and the 59 families who allowed the fence to cross their property. An estimated 2 million people came to the region to witness the flowing white line that captured coastal light as it hugged the curves of nature and accented the trappings of human industry. Pozzi recalls terrible traffic clogging the unimproved rural roads during that brief period. And then, two weeks later, “Running Fence” was gone without a trace, the materials disassembled, the cloth, cables, pipes and clips all donated to the ranchers. “If you look at some of the cattle guards out here today, you’ll see they’re made out of those pipes,” Pozzi says. “The temporal nature of the fence only added to the mystique,” says Mill Valley resident and photographer Chris Coughlin, who recently brought his aerial photos of “Running Fence” to light, as seen on these pages. In late June of this year, 50 years after Christo and Jeanne-Claude initiated the “Running Fence” project, members of several of the farming and ranching families who made the fence possible came together for a panel at an event organized by Elizabeth Bishop of the Tomales Regional History Center. When Coughlin heard about the event, it spurred him to search through boxes of slides he had in storage. Coughlin and his brother, Jim Coughlin, were taking flying lessons when the project was under construction, and had snapped approximately 30 photos from the air, which he never shared publicly, before now. “We were flying out of Sonoma’s airport, flying over the area in a Cessna 152, so we had the best seats in the house to see the project and to feel part of the flow of the fence,” Coughlin says. From Coughlin’s perspective, then and now, the project was “incomprehensible.” He believes Christo and Jeanne-Claude found a unique moment in time when people were willing to put aside conventions and fears of liability and accept the audacity of a project like “Running Fence.” “Over time, the beauty of the project has only grown, and like any good art, it’s still percolating 50 years later,” says Coughlin of the view from his training flights. “It still feels like, What did I see? Was it a dream?”

Kirsten Jones Neff is a journalist who writes about all things North Bay, with special attention to the environment and the region’s farmers, winemakers and food artisans. She also works and teaches in school gardens. Kirsten’s poetry collection, When The House Is Quiet, was nominated for the Northern California Book Award, and three of her poems received a Pushcart nomination. She lives in Novato with her husband and three children and tries to spend as much time as possible on our local mountains, beaches and waterways. For more on her work visit KirstenJonesNeff.Com.