Looking back at how one of California’s most iconic structures came to be, one could argue that San Francisco didn’t need the Golden Gate Bridge but that San Francisco and some counties to the north wanted the Golden Gate Bridge.

In the 1930s, when the bridge was built, San Francisco’s population was approximately 500,000 while Marin County had only about 50,000 people. At the same time, across the bay, as the San Francisco–Oakland Bay Bridge was being constructed, Oakland’s population was nearly 300,000. Oakland and San Francisco — each centers of commerce, citizens and culture — indeed needed an efficient means of moving people and things across the water.

Could the same be said of San Francisco and the more sparsely populated areas to the north? Hardly. And that is what made the Golden Gate Bridge such a tough sell.

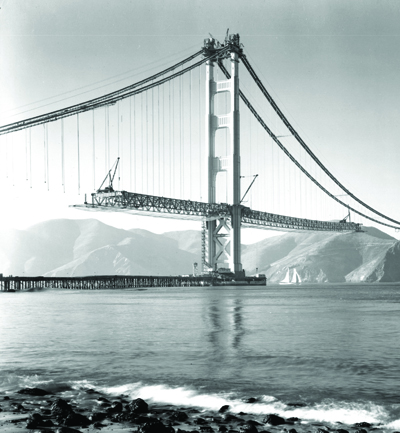

Serious talk of bridging the Golden Gate was initiated in the August 26, 1916, edition of the San Francisco Bulletin by columnist James Wilkins, who also had experience as a civil engineer. “Such a bridge, of course, would be of the suspension type,” Wilkins wrote, “and it will be longer than any other structure of its type in the world.” Surprisingly — considering today’s era of contentious public hearings, lawsuits, environmental considerations and difficult-to-negotiate labor contracts — in just over 20 years, Wilkins’ fantasy would become reality.

But it wasn’t as simple as it sounds. The building of the Golden Gate Bridge had all of the typical modern-day problems and more. In fact, many historians say constructing the Golden Gate Bridge was the easy part; getting to the ground-breaking was much more difficult.

The bridge concept was set aside when World War I erupted. But following the armistice, county supervisors from both San Francisco and Marin quickly voted to “investigate the possibility of bridging the Golden Gate.” Such stirrings caught the attention of a Chicago engineer named Joseph B. Strauss, already a builder of some 400 bridges, who came west to investigate such possibilities. Strauss, just over five feet tall and seeking engineering immortality, proposed an ugly, cagelike cantilever-suspension hybrid span and estimated its cost at more than $17 million.

The bridge concept was set aside when World War I erupted. But following the armistice, county supervisors from both San Francisco and Marin quickly voted to “investigate the possibility of bridging the Golden Gate.” Such stirrings caught the attention of a Chicago engineer named Joseph B. Strauss, already a builder of some 400 bridges, who came west to investigate such possibilities. Strauss, just over five feet tall and seeking engineering immortality, proposed an ugly, cagelike cantilever-suspension hybrid span and estimated its cost at more than $17 million.

If design wasn’t Strauss’ strong suit, smart, savvy and unrelenting salesmanship was. He understood San Francisco didn’t need a Golden Gate Bridge. If one were to be built, Strauss realized, it would be because folks in desolate areas to the north wanted it. So in January 1923, he went to Santa Rosa, where banker Frank P. Doyle (as in Doyle Drive) convened a daylong convention; there, a group named Bridging the Golden Gate was formed.

By May of that same year, the California Legislature, under the Coombs Bill, authorized the formation of the Golden Gate Bridge and Highway District, whose job it was to design, construct, finance and operate a bridge across the Golden Gate Strait.

The struggle wasn’t over. Over the next five years only six of the 13 Northern California counties eligible to join the Bridge and Highway District elected to do so, including parts of Mendocino and Napa counties, along with all of Sonoma, Marin and San Francisco counties and Del Norte County on the Oregon border. Why only six? Primarily because county supervisors knew that soon taxpayers would be asked to guarantee the construction bonds by allowing liens against their homes, croplands, vineyards and businesses in the event that the bridge wasn’t built or came in over budget, or that the tolls couldn’t cover construction costs. It was a big risk indeed.

page: |

1 |

| |

2 |

| |

3 |

| |

4 |

| |

5 |