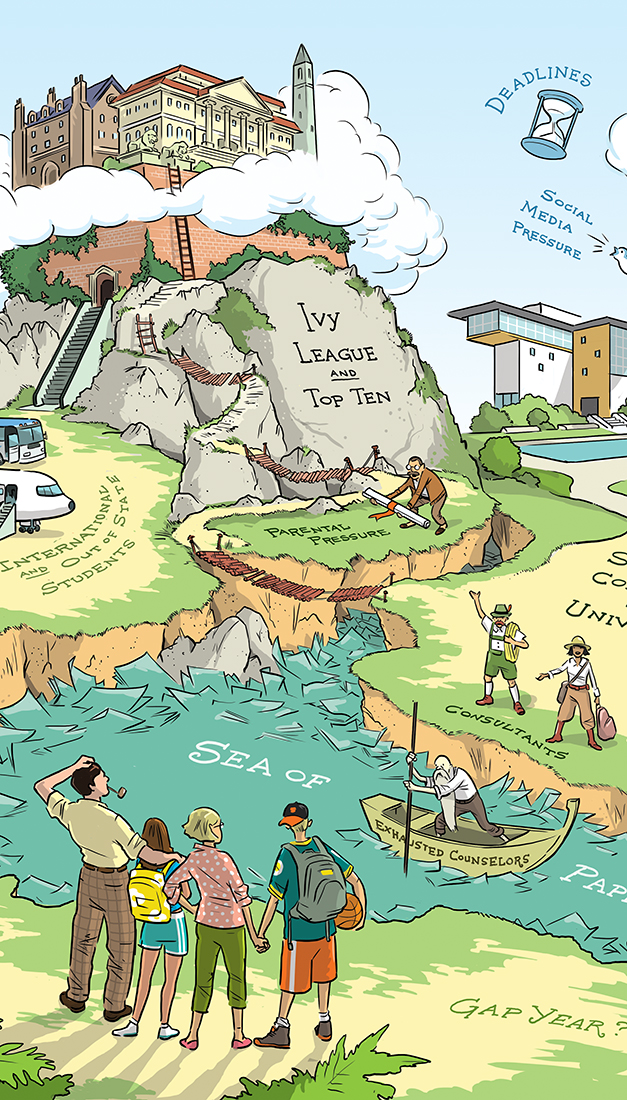

THIS FALL, WHILE some families are off visiting pumpkin patches or tasting wines in Napa, others are sitting down to begin the grueling college application process. Parents of high school juniors and seniors are poring over brochures from ivy-walled colleges, students are racing to perfect college essays and get last-minute teacher recommendations, and admissions officers are off wooing students who show promise.

THIS FALL, WHILE some families are off visiting pumpkin patches or tasting wines in Napa, others are sitting down to begin the grueling college application process. Parents of high school juniors and seniors are poring over brochures from ivy-walled colleges, students are racing to perfect college essays and get last-minute teacher recommendations, and admissions officers are off wooing students who show promise.

Anxiety has reached new levels in college admissions these days. Gone are the times when a 4.0 grade point average and a 1400 on the SAT all but guaranteed a space at Stanford or an Ivy League or UC school. Today, students with perfect grades and test scores are finding more closed doors than open ones. “You could have a 4.3 and 2200 SAT, but for selective schools like UC Berkeley and UCLA, it’s still going to be a reach,” says Laurie Favaro, a private college counselor in Marin.

The result? Students are studying harder, taking more AP courses than ever before and working with private college counselors who charge up to $400 per hour to help gain them a leg up on the competition.

“It’s a jungle out there,” says Gabrielle Glancy, an independent college consultant and former admissions director who has worked with students in the Bay Area for more than 25 years. She is also author of The Art of the College Essay, considered the book on that part of the application process.

“It’s much harder to get into college these days,” she says. “I recently started working with a student whose mom is a West Coast interviewer for Princeton. The mom told me confidentially she could never have gotten into Princeton if she applied today.”

The heightened competition stems from a number of factors. “There are too many students and not enough spots,” Glancy says. “Everyone prepares for standardized tests. The high-end students are higher-end and there are more of them.”

Indeed, students are graduating from high school and looking for colleges at record rates. According to the Western Interstate Commission for Higher Education, the number of high school graduates in the U.S. peaked at 3.4 million in 2011 but was still high as of 2013 at 3.3 million.

The acceptance rates at top universities illustrate the application challenges. This year, Stanford admitted just 5 percent of its 42,487 applicants, the lowest percentage for any institution ever. Compare that to 25 years ago when Stanford accepted 18 percent of its applicants. Similarly, the acceptance rate for Columbia University dropped from 65 percent in 1988 to less than 7 percent today. Yale’s acceptance rate went from 17 percent to 7 percent last year.

Beyond the Ivy Leagues, acceptance rates at the top 40 private and public colleges currently range between 10 and 30 percent. With space for no more than 16,000 freshmen, UCLA received applications from more than 112,000 students for 2015 — twice as many as in 2005 — giving it an admission rate of 22 percent. Smaller liberal arts colleges’ percentages were equally low.

A drop in state funding has led UC schools to admit more higher-tuition out-of-state and international students, squeezing out some California candidates. “The UC schools were definitely hard to get into this year,” says William Breck, a 2015 Redwood High School grad who now attends University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill. “Many kids [I know] didn’t get into UCLA and Berkeley. The general vibe is that getting into the UCs is basically a lottery. The UC readers have so many applications to get through and they don’t take recommendation letters, so admission is very unpredictable.”

A drop in state funding has led UC schools to admit more higher-tuition out-of-state and international students, squeezing out some California candidates. “The UC schools were definitely hard to get into this year,” says William Breck, a 2015 Redwood High School grad who now attends University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill. “Many kids [I know] didn’t get into UCLA and Berkeley. The general vibe is that getting into the UCs is basically a lottery. The UC readers have so many applications to get through and they don’t take recommendation letters, so admission is very unpredictable.”

That unpredictability has prompted kids to apply to more schools than their counterparts in the past. Favaro says her students apply to 10 to 12 schools on average, some as many as 20.

Parents Feel the Stress

Students aren’t the only ones feeling the pressure.

“Parents today are more involved and more worried than they used to be,” Glancy notes. “High school college and guidance counselors are overworked. One counselor could have 600 students to work with. With the new SATs in spring 2016 (see sidebar) things will get even more complicated. Even trained professionals have a hard time keeping up with it all. How are parents supposed to do it?”

Audrey Shapiro, a Mill Valley parent, agrees the admissions gambit is much more complicated than back when she applied to colleges. “Most of us (parents) applied to one school, maybe two, where we knew we had the numbers to be admitted,” says Shapiro, whose two kids graduated from Tam High and now attend University of Wisconsin and Indiana University. “The process is very different for our kids. More kids than ever are going to four-year colleges. It’s a competitive world and harder to get jobs without a college degree. So parents worry — and then kids worry.”

Watching her kids stress out about applications was difficult. “We tried to take a measured approach and keep things in perspective,” she says. “This was not always easy when it seemed everyone around them was making it a very big deal.”

In affluent Marin, it’s become common for parents to hire private counselors, to help their child with everything from choosing schools and tracking application deadlines to preparing for standardized tests and writing essays. Nationwide, families are spending more than $400 million a year on these “independent education consultants,” who often charge upwards of $150 per hour, according to the Independent Educational Consultants Association (IECA). Full college admissions packages, which do not include the cost of ACT or SAT test prep, average $4,035 per student, according to IECA.

But one of the hidden benefits of such counselors is easing tensions between students and parents during such a high-stakes time. “My college counselor was great because it wasn’t up to my parents to hound me for supplements or to finish applications,” says Patty Kusnierczyk, a sophomore at the University of Nevada and graduate of St. Ignatius Prep (she chose UN because it has her major, is less expensive than other options and because it is close to Tahoe). “This created a much more peaceful home than it could have been during my junior and senior years.”

Students Speak Out

Much of the anxiety around college admissions comes from back-and-forth conversations and chatter among classmates, according to many students in Marin.

“I found one of the more frustrating parts of the application process to be the gossip within my senior class that came from it. My peers constantly wanted to know where everyone was applying and whether they were accepted or not,” says Lena Kristy, who graduated from Marin Academy in 2012 and from UCLA in 2015. “I remember one day my friend asked me, ‘So Lena, where are you applying to college?’ After I spat out the entire list of schools to her, she announced that she was keeping her list secret. I was mortified.”

Social media exacerbates the stress, St. Ignatius graduate Kusnierczyk says. “Online, you see the smartest kids are going to certain schools and you think that to prove you’re smart you should go there too,” she says. So “a lot of the time, students don’t choose the ‘best fit’ but the school with the big name or reputation or schools where you know people who already go there.” Also, “people you know who are already in college post things to make it look like they’re having the time of their life and you believe it. What people don’t tell you is that no matter where you go, your first semester away at college is challenging academically and socially. Social media doesn’t do justice to that fact.”

For Kusnierczyk, the hardest part of the process was trying to keep up her grades while getting all her applications “perfect and in on time.” Peer pressure upped the ante. “A lot of the time you’re competing with your friends for your dream schools,” she says. “I remember I’d rank myself and judge myself based on my classmates’ applications. It was difficult to congratulate those who got into schools before I did because you’re concerned about yourself.”

For Kusnierczyk, the hardest part of the process was trying to keep up her grades while getting all her applications “perfect and in on time.” Peer pressure upped the ante. “A lot of the time you’re competing with your friends for your dream schools,” she says. “I remember I’d rank myself and judge myself based on my classmates’ applications. It was difficult to congratulate those who got into schools before I did because you’re concerned about yourself.”

Katie Toepel, another St. Ignatius grad and now a sophomore at the University of Texas, Austin, says the application process is tense on two counts. “There’s the stress of getting accepted into one of these so-called brandname colleges, accompanied with the stress of the aftermath of being rejected from them,” she says. “I know those two things probably sound the same, but they’re slightly different. The ‘stress of acceptance’ is the standard anxiety surrounding not knowing where you stand against all the other admits, not knowing whether a college likes you or not, and not knowing where you’re headed next year, in general. The ‘stress of the aftermath’ is the anxiety over telling your peers that you didn’t get into X, Y or Z college, because they might think you’re inferior, dumb or unworthy.”

Another Way

In fact, for many students, aiming straight for university placement doesn’t always make sense. For those hoping to save money, explore the world a bit, or improve their grades to get into a better school later on, community college can be a great choice. Approximately 15,000 students make the switch from two-year community colleges to UC schools each year. If you walk around a UC campus, one in every three students you see is a transfer from community college.

Sam Pannepacker, a Redwood High School graduate, worked at the Apple Store in Corte Madera and took classes at the College of Marin for two years before transferring to the Pratt Institute in Brooklyn, where he is studying industrial design. “The uncertainty of how I wanted to spend my college career, and really the rest of my life, made spending a little extra time exploring new paths the best option,” he recounts. “I hoped to transfer in to a state or UC school with my credits.”

But working at Apple opened his eyes to “the relationship people have with products” and inspired his interest in industrial design. He also improved his people skills, discovered a direction and learned to be responsible for his own schedule — benefits he couldn’t have envisioned when he graduated. “Once I moved to Brooklyn, the freedom of living away from home in a city was new, but was not overwhelming as I imagine it would have been (straight) out of senior year.”

A Needless Frenzy?

While the admissions process can seem overwhelming, there are ways to get through it without breaking a sweat or the bank.

First, parents should take a close look at the numbers before they panic. Sure, admit rates are dropping for the most selective schools, the 100-or-so that accept fewer than 25 percent of applicants. But according to the College Board, a century-old nonprofit created to expand access to higher education, the U.S. and Canada have more than 2,500 accredited four-year colleges, and most of them accept two-thirds of applicants.

A 2012 report by the National Association for College Admission Counseling is also less dire: it found that colleges have actually become only modestly more selective over the past 10 years. The average public four-year college admitted 66 percent of applicants in 2013, down from 70 percent a decade earlier. For private schools, the 2013 acceptance rate is down from 70 percent to 63 percent.

A 2012 report by the National Association for College Admission Counseling is also less dire: it found that colleges have actually become only modestly more selective over the past 10 years. The average public four-year college admitted 66 percent of applicants in 2013, down from 70 percent a decade earlier. For private schools, the 2013 acceptance rate is down from 70 percent to 63 percent.

Second, keeping expectations in check can remove a lot of the pressure, angst and drama. In her book Teach Your Children Well, Marin psychologist Madeline Levine writes about a straight-A student who “lies in bed for days” after rejection from her top-choice college. “She will not get up, and when I visit her at home, all she can say through her streaming tears is, ‘It was all for nothing. I’m a complete failure.’”

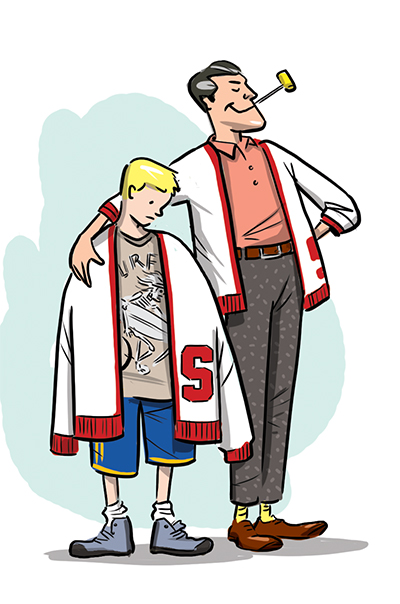

In a local talk Levine gave on “raising successful children,” she reminded Marinites that not every kid is meant to go to Harvard or Stanford. She also cautioned parents against living out their hopes and dreams through their children: “Dad didn’t get into Harvard, so he pushes his child to get into Harvard. He buys a Harvard bumper sticker even before the kid gets in.”

For a pivotal destination like college, “status shouldn’t matter,” Levine adds. Students should choose a school “where they will find their tribe, where they will feel comfortable, engaged and valued.” Indeed, examples abound of successful and influential people who attended state universities and far-from elite schools. Oprah Winfrey graduated from Tennessee State; Warren Buffett went to University of Nebraska.

Gregg Easterbrook of the Brookings Institute supports that view. “An ivy diploma reveals nothing about a person’s background, and favoritism in hiring and promotion is on the decline,” he wrote in an Atlantic piece called “Who Needs Harvard?” in 2004. “Most businesses would rather have a Lehigh graduate who performs at a high level than a Brown graduate who doesn’t.”

Students concur. “Just know that wherever you end up, whether it’s your reach or your safety school, you can be happy,” says Evy Roy, a Marin Academy graduate who is now a senior at Tufts. “It’s about the communities you find and the people you meet, not the school’s prestige.”

Redwood High grad William Breck adds, “College isn’t all about the name of the school; it’s about what you do there. If kids really understand that, then making a decision will be gratifying, not stressful.”

A New Look at the SAT

IN 2016, THE SAT returns to a 1600-point test rather than the 2400-point model implemented in 2005. Instead of the current Reading and Writing sections that count for 800 points each, the verbal half of the test will revert to a single 800-point Evidence-Based Reading and Writing section, similar to the old exam. Math will still be an 800-point test. The essay will become optional. Test-wide, the material covered will adhere more closely to the Common Core standards for both Reading and Math. The quarter-point penalty for wrong answers will also be removed.

Overall, these changes will bring more advanced content and harder questions. For example, the new reading section includes passages typically found on the more difficult SAT Subject literature test (Subject tests are separate content-based tests used to show achievement in a specific area). To gauge deeper comprehension, three of the 24 reading items don’t just test a student’s ability to spot a right answer, but require explanation of why it is correct. These “show me the evidence” questions require students to identify where they found support in the passage for their choice. Since these questions come in pairs, if you err on the first question, you’ll most likely get the second one wrong too.

The math section of the new SAT includes a greater number of Common Core–type questions, which test not just problem-solving ability but understanding of underlying math fundamentals in real-world scenarios. Word-based math problems abound: students will need to step back to understand what the variables and the constants signify. One practice test taker said it felt like a high school Algebra II/ trig final, touching on items like coefficients, constants, smooth curves and quadratic equations.

Students will have more time per question in the new SAT, but the more difficult problems warrant that. In fact, “I’m recommending that none of my students take the first three rounds of the new SAT (March, May and June of 2016),” Anthony Green, the New York–based SAT and ACT tutor to the rich and famous, told Business Insider. “Why let students be guinea pigs for the College Board’s marketing machine?” He recommends the ACT instead.