Would you take this bait? Hundreds of acres of prime Marin real estate are yours, provided you have “a school or seminary of learning” completed on the site in two years.

No way, you say? It takes too long to get any project through planning, entitlements, design review boards and final approvals? Maybe so, but that was the offer tendered in 1853 when Marin was a wide-open county and San Rafael had a dozen or so disheveled homes and a mission in even worse condition.

And, it wouldn’t be easy, because the person capable of pulling off the feat was 2,800 miles away.

Here’s the story: on his deathbed, San Rafael land grantee Timothy Murphy promised 317 acres of land to Joseph Alemany, the first Archbishop of San Francisco. But as with any good Irishman, there was a catch to Murphy’s offer: the acreage would revert back to Murphy’s heirs unless a school was operating on the premises within two years. And as often happens, the best man for the job was . . . a woman. At the time, however, Sister Frances McEnnis was living with the Sisters of Charity of Saint Vincent de Paul in Emmitsburg, Maryland.

According to A Mission That Endures: A History of St. Vincent’s School for Boys by Peter Rudy, when notified by Archbishop Alemany that the Sisters of Charity were needed to care for children orphaned by a recent cholera plague, Sister McEnnis and a small band of nuns agreed to make the hazardous trip and immediately headed west. After a grueling cross-country journey, they raised the necessary funds and made sure the school was open for students on January 1, 1855—beating Murphy’s deadline by ten days. As for naming the school, Sister McEnnis reached back to her roots: it would be called St. Vincent’s.

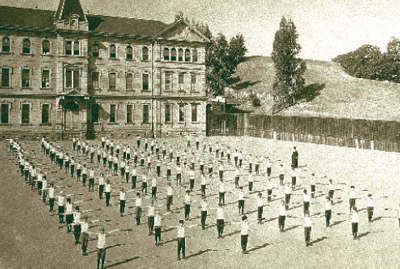

By 1868, the orphanage was housing 150 boys. By 1884—after initiation of farming operations, building expansion and outreach, and bringing in the Dominican Sisters to help with teaching—St. Vincent’s was home to nearly 500 orphaned as well as neglected or abused kids.

By 1868, the orphanage was housing 150 boys. By 1884—after initiation of farming operations, building expansion and outreach, and bringing in the Dominican Sisters to help with teaching—St. Vincent’s was home to nearly 500 orphaned as well as neglected or abused kids.

On May 19, 1888, half the St. Vincent’s campus was leveled by a disastrous fire; fortunately, no one perished. As one era ended, another began. Soon an expansion was under way, involving gas-lighting, a new wing and a pre-graduation technical training program for the boys. In 1893, when a consistent source of water for bathing, drinking and fire protection was discovered nearby, St. Vincent’s had not only recovered from the fire, but was well on its way to a safe and independent existence.

Around the turn of the century the Dominican Sisters stepped out from St. Vincent’s and the Christian Brothers stepped in. A 34-piece band plus football and baseball teams were worked into the curriculum. In the 1920s, Father Francis McElroy was named director of St. Vincent’s; his first moves were to bring back the Dominican Sisters and commence a rebuilding effort, which produced the Renaissance-style buildings—including the spectacular Most Holy Rosary Chapel—that dominate St. Vincent’s today.

“Father McElroy was a friendly man, a wonderful man,” recalls Angelo Leoni, 87, a resident of St. Vincent’s from 1934 to 1937. “He was very proud of the school and we were always afraid of offending him.” Dr. Leoni, who went on to attend USF and medical school in the Midwest, has been a Petaluma general practitioner for decades (as well as father of ten and grandfather to 27). “St. Vincent’s set me on a good path,” he says. “Everyone had a job; we all had to work.”

Mill Valley’s Jim Conley, now 83, also lived at St. Vincent’s during the 1930s, but had a slightly different experience. “Even though I was always in trouble, Father McElroy was like a father to me,” he says. Crowley’s mother died when he was six and, in May of 1936, when he was 12, Father McElroy tenderly informed Conley that his father had just passed away. “Without Father McElroy and St. Vincent’s, I’d be in San Quentin today,” he confides. “I was definitely headed that way.”

About 325 boys lived at St. Vincent’s when Conley and Leoni were there. By the time Elvy Zanandrae entered at the start of World War II, the school was home to nearly 350. “Father McKenna had replaced Father McElroy,” he recalls, “and though in his picture he looked mean as all hell, he was a kind and nice person.” By his own admission, Zanandrae, known as “Zany” at St. Vincent’s, “was always getting into trouble, quite a few fights; I didn’t like the confinement.” Yet in retrospect, he feels his years there were good for him: “The school was practically self-sufficient and there was always competition—football, baseball, basketball—and being on a team was the only way we could get off campus and meet girls.” Zanandrae, now 72, lives in Larkspur with Lynn, his wife of 47 years.

In the 1950s and ’60s, St. Vincent’s evolved from its institutional past to become a residential facility serving a younger male population in need of longer-term acre. Then in the 1980s, St. Vincent’s established a Foster Home Program to enhance the prospects for some of the boys returning to their birth parents. St. Vincent’s also created the Timothy Murphy School—named for the Irishman who issued the long-ago deathbed challenge—to provide for the boy’s special needs. Under the leadership of Michael Marovich, the school also became more attached to the Marin County community. A 25-member advisory board was created and special projects—a pumpkin patch, a Christmas tree lot—brought the surrounding Marinites closer to the organization and its mission.

Today, St. Vincent’s is part of the Catholic Charities CYO, a nonprofit organization that provides programs and services to boys regardless of religious affiliation or socioeconomic status. The school is registered as a residential treatment center with the State of California’s Department of Social Services. Currently, St. Vincent’s accommodates 60 at-risk boys from abusive and troubled backgrounds.

Today, St. Vincent’s is part of the Catholic Charities CYO, a nonprofit organization that provides programs and services to boys regardless of religious affiliation or socioeconomic status. The school is registered as a residential treatment center with the State of California’s Department of Social Services. Currently, St. Vincent’s accommodates 60 at-risk boys from abusive and troubled backgrounds.

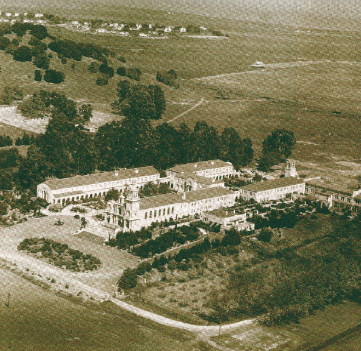

EDITORIAL NOTE: Unfortunately, St. Vincent’s itself is currently at risk. Due to a lack of adequate funding, its magnificent 80-year-old buildings are falling into serious disrepair. This fall, the Marin County Board of Supervisors will be considering restrictive land use policies recommended by the county planning commission for St. Vincent’s 780 acres of land. If approved by the Board of Supervisors, these policies will effectively preclude any opportunity for St. Vincent’s to develop less than 15 percent of its acreage for an affordable senior citizens’ housing complex. If allowed to proceed, such development would generate funds necessary to build new facilities, restore the historic buildings, and establish an endowment enabling St. Vincent’s to continue the work that was begun over 150 years ago.

Image 2: In 1934, two boys admire the Most Holy Rosary Chapel, which was completed in 1930 and still holds Sunday services.

Image 3: St. Vincent's buildings-located off the 101 freeway between San Rafael and Novato-and completed in 1930, are now falling in disrepair.