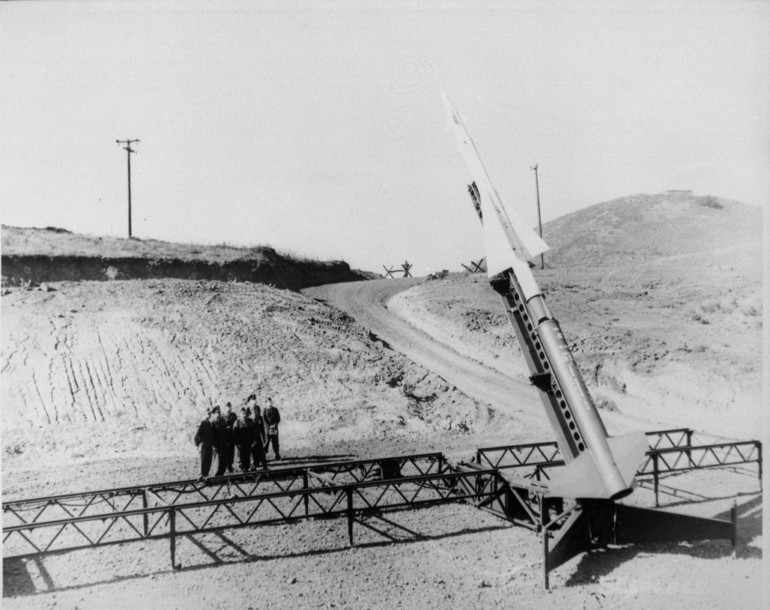

A web of narrow pathways winds up from Rodeo Beach, through pink ice plant blooms and over rugged, sandy outcroppings, to hilltops with 360-degree views of the San Francisco skyline, velvety green cliffs, and a royal blue sky arching over the wild ocean below. The Marin Headlands offer visitors a front row seat to the peaceful majesty of our planet, which makes it especially difficult to process the park’s legacy of near-destruction. The land housed a maze of tunnels, bunkers, radars, elevators and magazines that made up the SF-88 site at Fort Barry, one of 280 Nike nuclear missile launch stations built across the nation between 1953 and 1974 in the Cold War era.

The Nike Hercules anti-aircraft missiles, operated by the U.S. Army, were considered the last line of defense against Soviet fighter planes carrying hydrogen bombs, in the case that they eluded the U.S. Air Force and Navy. The nooks and crannies of the Marin Headlands offered ideal camouflage for the maze of spaces housing the warheads and their operators. These missiles each carried a force greater than the bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Japan, combined, and their operators were young soldiers, some only 18 and 19, whose training was focused on mental preparedness to execute a launch. Oral histories and docent tours given by veterans at Fort Barry — the only Nike site in the country preserved as a museum to remind the public of the reality of this chilling era — tell tales of false readings and launch emergencies; one countdown, in particular, brought our nation perilously close to nuclear war.

Today, a preponderance of school groups and history buffs visit the Fort Barry museum; the rest of us frolic on the beach and along the nearby hiking trails. This is the human way — until something presents itself as an immediate threat, we find it difficult to pay attention, especially if the issue feels complex, or we see no clear path of action to create change. “One of the major problems is that it isn’t until the situation is so catastrophic that people engage, and with nuclear arms, at that point it’s really too late,” says Mill Valley resident Pam Hamamoto, former ambassador to the European Office of the United Nations in Geneva under President Obama.

Currently, Hamamoto sits on the board of Ploughshares Fund, the largest U.S. philanthropic foundation focused on nuclear weapons. “We’re more vulnerable than people understand,” she continues. “We’ve been close so many times, so it’s amazing that nothing catastrophic has happened, by accident or malice.”

The issue of nuclear arms is complex because it involves a global world order, national security policy, our military-industrial complex, defense budgets, and both domestic and international politics — and an understanding of history. In brief: In the 1940s, physicists developed the ability to use nuclear fission and fusion to build weapons, and the U.S. and other nations began to build nuclear warheads. Hiroshima and Nagasaki offered a tragic illustration that no nuclear war is acceptable to humanity, and the defense strategy of global leaders, most notably the U.S. and what was then the Soviet Union, evolved into a strategic approach called Mutually Assured Destruction, or MAD, a national security approach based on the idea that both parties have nuclear weapons of mass destruction, which offers assurance that neither party will use them. This strategy led to an arms race (the SF-88 site in the Headlands was part of the U.S. arsenal buildup) during the Cold War between the U.S. and the Soviet Union, and established the belief that persists globally that more nuclear weapons will secure our safety. Although just a few hundred large-scale nuclear weapons could end life on earth, there are more than 13,000 nuclear weapons left on the planet, 90% of which are in the U.S. and Russia, while the remainder are in China, France, India, Israel, North Korea, Pakistan and the United Kingdom.

Today, a growing number of national security analysts and military leaders believe the MAD strategy and the associated spending of trillions of dollars worldwide on nuclear arms, is archaic. Elizabeth Warner, also a Marin County resident, is the Ploughshares Fund managing director who, like Hamamoto, has become a vocal leader in the disarmament community. “There is a myth around deterrence we would like to dispel: Nuclear weapons do not keep us more safe,” says Warner. “There are people who were in charge of our nuclear weapons arsenal who have now said that they see no mission where they would use them.”

In the four years Donald Trump was in the White House, his administration back-tracked on decades of nuclear arms-control progress, expanding the nuclear arms budget and arsenal; pulling out of international treaties and agreements; and escalating tensions with Iran and North Korea, two countries actively building their nuclear programs. Each transition to a new U.S. administration offers an opportunity for new nuclear disarmament strategy and negotiations. Because unilateral disarmament is not considered a viable strategy, national security specialists with global expertise in nuclear arms control are critical to an administration with a genuine interest in arms reduction, and this heightens the importance of the work of organizations like the Ploughshares Fund. Last June, the world watched as President Joe Biden and Russian President Vladimir Putin shook hands and agreed to an extension of the New START treaty (the New Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty with Russia, originally signed in 2010) and to resume stalled nuclear arms talks. Around the same time, Tom Collina, director of policy at Ploughshares Fund and former Secretary of Defense William J. Perry, who cowrote the recently released The Button: The New Nuclear Arms Race and Presidential Power from Truman to Trump, delivered a joint testimony before the Senate Armed Services Committee (SASC) focusing on ending the current policies of presidential “sole authority” to use nuclear weapons and establishing “no first use” policy, while maintaining the Ground-Based Strategic Deterrent programs.

The report card on President Biden’s nuclear arms policy is still out, Warner says. As a candidate, he sounded like a strong arms-control proponent, and when he took office his team turned to Ploughshares Fund advisors, among others, to develop their nuclear arms policy and budget. But so far, from Warner’s perspective, the administration’s actions have been mixed. “In his campaign, Biden made promises around presidential sole authority and no first use, extending the New START treaty and JCOA (the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action, otherwise known as the Iran nuclear deal), all of which are positive and would make the world a safer place,” she says. “The Biden administration did extend New START very quickly, but the budget that they released in May has full funding for new ICBM’s (Intercontinental Ballistic Missiles) authorized under Trump, so it’s a modernization of existing weapons and creating new weapons. Our hope was that he would cut that program.”

Biden’s budget decision to extend Trump’s ICBM development and modernization program was especially discouraging, Warner and Hamamoto agree, because it represents a missed opportunity in the form of approximately $264 billion (over the 50-year lifecycle of the missiles) of taxpayer funds. “This would have been an opportunity to cut back nuclear arms spending and to redeploy those funds elsewhere,” Hamamoto points out. Both women applaud Representative Ro Khanna (CA-17) and Senator Ed Markey (D-Mass), who in March introduced a bill called Investing in Cures Before Missiles (ICBM) Act, which would “stop the further development of the Pentagon’s $93–$96 billion ground-based strategic deterrent (GBSD) intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) and direct those savings towards development of a universal coronavirus vaccine and towards the battle against other types of biothreats.”

In her role at Ploughshares Fund, Warner has championed a program called The Women’s Initiative, striving to bring a diversity of voices to the nuclear disarmament policy table. “If we’re going to dismantle nuclear colonialism that was created, for the most part by men, under a veil of secrecy, to create something better, we need to have different voices at the table,” she says. An expanded perspective on the meaning of public safety might include, for example, the prioritization of public health and climate change amelioration over nuclear arsenal expansion, and a greater recognition of the injustice built into our nuclear mining and testing programs that have resulted in devastating environmental, financial and health effects in communities of color in the Mariana Islands, on the Navajo reservation, and in that states of Washington and Colorado. Here in the Bay Area in 1946, the Hunter’s Point shipyard began receiving contaminated ships used for testing in the Mariana Islands, and housed a Navy nuclear defense lab, resulting in at least 91 radioactive sites across the square mile yard. Pointing to this legacy, Warner sees her work around nuclear arms as an extension of her lifelong “commitment to justice and to a better global order.” For Hamamoto, whose father is Japanese, the history of Hiroshima has loomed large in her consciousness, drawing her attention to the issue of nuclear arms.

It’s hard to imagine that nuclear war is possible, and easier to live our daily lives assuming that it could not happen. In Marin County, where we enjoy our open spaces, including the lands around the former nuclear missile site at the Headlands, we live free of the urgent crises of extreme poverty or war. We are in a position to follow budget and policy decisions carefully, to educate ourselves about the cost and peril of nuclear arms. Hamamoto hopes we can begin to include nuclear weapons proliferation in the “everyday conversations about things we care about.” From Warner’s perspective, Marinites recognize that there would be massive disruption to their work and to the global economy, as well as unimaginable humanitarian tragedy in the case of a nuclear event, yet we don’t remain engaged and vigilant around the issue. She points out that $1 trillion dollars of taxpayer money will go into maintaining and modernizing our nuclear arsenal over the next 30 years. “That’s $1 trillion dollars on weapons we will not use,” says Warner. “Pick any societal or environmental issue — think about what we could do with just a portion of that.”

For more on Marin:

- Who Was Archie Williams? The Story Behind the Renaming of a San Anselmo High School

- Dorothea Lange’s Steep Ravine: How an American Photography Icon Found Her Sanctuary in Marin

- The Story of Forest Farm: How the San Geronimo Valley Became Home to the Country’s First Racially Integrated Summer Camp West of the Mississippi