Drive along Tiburon Boulevard — but this time see it differently. See it like Dr. Martin Griffin sees it, and suddenly Lyford House isn’t just a sweet yellow Victorian, it’s headquarters of the Richardson Bay Audubon Center, overlooking the only open water sanctuary in San Francisco Bay. If the tide is low, shorebirds walk the wide mudflats of the undeveloped shore, heads down as they hunt for food. Griffin turns 100 this month, but he’s quick to notice and identify every species.

If it weren’t for Griffin and his fellow “rebels with a cause,” you wouldn’t be enjoying these beautiful vistas from Tiburon Boulevard. Instead, you’d be zipping along a freeway to Angel Island, Alcatraz, and Telegraph Hill. There would be no hills and no wild shoreline, because in the 1950s developers would have bulldozed the hills of Tiburon to fill Richardson Bay and built a new city called Reeds Port, with housing for 10,000 people.

Fortunately, that’s not what happened, in large part because in 1957, when dredging of Richardson Bay for Reeds Port had already begun, Elizabeth Terwilliger of the Marin Audubon Society called Griffin, then a young doctor living in Sausalito. “We’d like you to be on the board of directors,” she said, adding, “I won’t take no for an answer.”

Griffin jumped at the opportunity to learn from Marin’s first environmentalists, notably Terwilliger and Caroline Livermore. “I literally apprenticed myself to Caroline Livermore,” he recalls. “She and her ‘ladies’ as she called them had the vision, connections, and clout to be effective, and I mobilized my medical practice and colleagues to join them in helping save the bays and lagoons of Marin County.”

It was the start of a lifetime of environmental activism, with Griffin frequently called on to play leading roles in preserving Richardson Bay, Bolinas Lagoon, Tomales Bay, and Point Reyes National Seashore. As part of that effort, he also had to out-maneuver those who wanted to develop a freeway system up the west coast of Marin and build a nuclear power plant straddling the San Andreas Fault in Bodega Bay. Working with other passionate conservationists and organizations including Audubon and Marin Conservation League, Griffin leveraged his knowledge of wildlife, county politics, water supplies, and real estate, plus his influence as a respected doctor to protect the county’s environmental treasures. His go-to strategy in many of these campaigns was to look for “keystone” pieces of property which, when bought and protected, would make a larger project untenable for developers.

Griffin himself was a keystone. It wasn’t he alone who saved Marin from the excesses of development. But he was an essential part of the success of the so-called “rebels with a cause.” And they were extremely successful: Their grassroots political victories protected two thirds of Marin including the encircling bays and marshlands and the Point Reyes Peninsula. They stopped the planned construction of freeways on the Marin-Sonoma-Mendocino coast, got the salmon rivers of the North Coast (except the Russian) protected as Wild and Scenic Rivers, ensured that every California River requires a watershed management plan, legally preserved all the state’s tidelands, and gave the public access to much of the 1,100 mile California coast.

Griffin achieved all this while also maintaining a medical practice in Marin, getting a degree in public health, and working in State Hospitals, most notably earning a Governor’s Award for helping to eradicate an epidemic of hepatitis B from California’s State Hospitals.

Griffin turns 100 later this month, but he’s still busy saving Marin’s wild places — at the moment, he’s working on the issue of ranching within Point Reyes National Seashore. It took a few days to get a time to sit down with him to talk about his upcoming birthday and his reflections on a long career.

“I saw the best of wild California before World War II, and I idolized Marin and Sonoma,” he said as he settled into a chair on his back patio, which edges against Richardson Bay. He flashed a smile. “I can’t let go of any opportunity to save nature. Along with the help of the wonderful naturalists and friends I have known over the years, I think I’ve made a real difference in Northern California.”

What can you say but, “Thank you?” The hard part is saying it big enough.

If you were a young activist starting out today, what would you tackle first, why, and how?

I’d do what I’m doing right now, joining in the push to end ranching in Point Reyes National Seashore. It has one of the greatest populations of elephant seals and harbor seals, and millions of birds on the flyway. But there are cattle grazing right up to the edge of the Estero and manure draining in. Ranching is important in West Marin, but we need to keep the park wild.

After winning that fight, I’d get involved in protecting other parts of the National Park Service. It’s a treasure, and it’s under threat now.

Somehow I thought you’d say climate change would be your priority.

Oh, climate change is hugely important! The need to protect Point Reyes is immediate, do-able, and would in itself reduce emissions, which is why I’d start there. I’d take on climate work alongside that, both immediately and in the long term.

You’ve made a career in public health as well as protection of the environment. How do you think Marin’s open spaces and wild coasts support public health in the county?

People are only as healthy as their habitat, same as animals. We need open space because we need earthworms, butterflies, and land that’s not treated with pesticides and herbicides. When I drive to Sacramento these days, there are almost no bugs on the windshield. The big chemical companies seem to be unstoppable and all-powerful. I think overuse of chemicals was what led to my granddaughter Gina’s death from leukemia. She died at 15, quite possibly from all the chemicals used in the vineyards.

You haven’t won every battle you’ve fought, but you’ve got back in the ring time and again. Today’s environmentalists have been dealt some stinging setbacks in the past few years. What would you like to tell them to help them keep going?

I lost some big battles, mostly in Sonoma. But there’s always something that can be done. I’ve always tried to make a difference and improve habitat wherever I had the opportunity. So when I bought the ranch at Hop Kiln, we did a lot to improve it and protect the Westside Road area around it from development and the growth of traffic. [Griffin and his wife Joyce received the Healdsburg Museum and Historical Society’s award for historic preservation of an industrial enterprise in 1997]. We got the river designated as endangered. And Joyce and I gave Gina’s Orchard, a 26-acre stretch of creekside property in Sonoma, to the Bishop’s Ranch retreat center, which is across the road from Hop Kiln.

My old friend Peter Behr would say, ‘Conservation victories can be temporary, while the losses are permanent.’ That’s why in 1972, the directors of Audubon Canyon Ranch, including myself, took the first steps to create an organization dedicated to training volunteers to be effective advocates for environmental planning. It was one of the most significant actions of our lives because this nonprofit — the Environmental Forum of Marin — is training up new generations to protect and build on the legacy we created. Every county needs an organization dedicated to defending the natural environment at a grassroots level.

“I Think I’ve Made a Real Difference”: A Timeline of Dr. Griffin’s Accomplishments

1920 Loyal Martin Griffin, Jr., was born in Ogden, Utah, in a cabin on the banks of the Ogden River. The family moved to Portland, Los Angeles, and finally Oakland, where Griffin became an Eagle Scout and attended Oakland Technical High School.

1936-1942 ROTC (Reserved Officer Training Corp High School & UC); war declared 1941.

1942 Graduated from UC Berkeley with a degree in zoology and botany.

1943 Attended Stanford Medical School — Army Specialized Training Program, ASTP.

1946 Earned MD from Stanford Medical School. Served as a commissioned Captain US Army Medical Corp — Active duty 6th Army Presidio SF.

1950-1967 Practiced in Marin County for 17 years, where he helped start the Ross Valley Clinic, Ross General Hospital, Kentfield Psychiatric Hospital, and The Tamalpais retirement center.

1960 Purchased Hop Kiln Ranch in Sonoma and began restoring it, earning National Historic Trust status.

1961 Helped found Audubon Canyon Ranch and was instrumental in purchases of key parcels which prevented the construction of a fourlane freeway, and helped protect the wild watersheds surrounding the Point Reyes National Seashore from development. Today ACR includes 5,000 acres of wildlife sanctuaries on the watersheds of Bolinas Lagoon, the San Francisco Bay, Tomales Bay, Sonoma Creek, and the Russian and Eel Rivers.

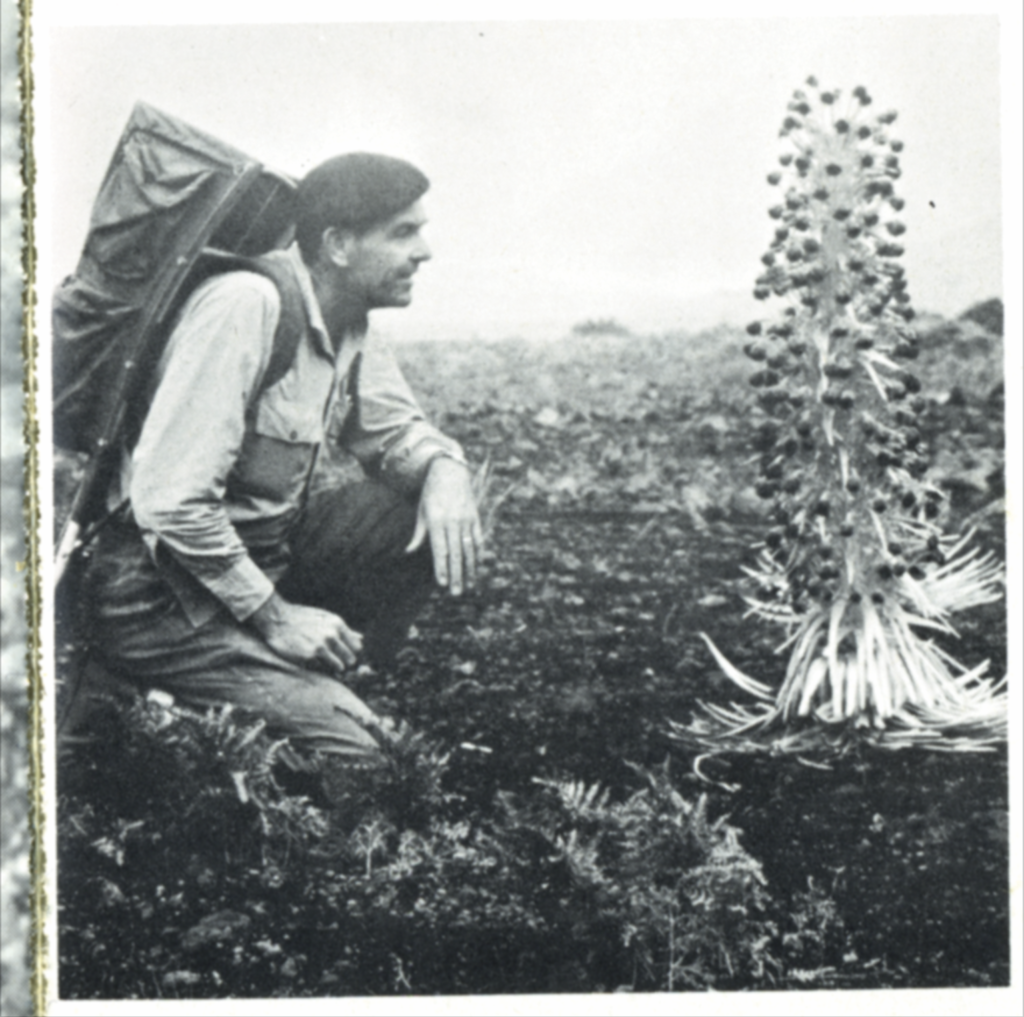

1968 Participated in a scientific mission to Maui that laid the groundwork for the Kipahulu Valley’s inclusion into Haleakala National Park (including the Seven Sacred Pools on the coast).

1969 Became interested in public health after doing wildlife work in Nepal.

1972 Earned master’s degree at UC School of Public Health.

1972 Cofounded Environmental Forum of Marin.

1973 Elected as a director of the Marin Municipal Water District and helped prevent the building of a coastal aqueduct from the Russian River. This preserved 22,000 acres of watershed and native plant habitats.

1973 Found a deserted 1873 Italianate Victorian house in Fulton and moved it 20 miles across the river to his property. The County designated it a County Historic Landmark.

1975-1990 Served for 15 years as Public Health Director at the Sonoma State Hospital for developmental disorders in Glen Ellen.

1975 Founded Hop Kiln Winery on the Russian River. Intrigued by the variety of grapes he discovered at Hop Kiln Ranch, he studied winemaking techniques used in Tuscany, Sicily and Germany and became a member of the California Wine Institute. Produced 24,000 cases of award-winning wines annually.

1984 Appointed Chief of the Hepatitis B, and later AIDS, Task Force for the 11 State Hospitals. On retirement, given the Governor’s Award for successful Hepatitis B Immunization Program.

1990 Founded the Russian River Task Force in 1990 to bring under control deep pit gravel mining in the Russian River aquifer which was affecting drinking water quality in Marin and Sonoma counties, a 15-year battle. Founded the Russian River Environmental Forum, and cofounded Friends of the Russian River, now the Russian Riverkeeper. Griffin and wife Joyce gave the 45-acre Griffin Russian River Riparian Preserve to the Sonoma Land Trust and the 26-acre “Gina’s Orchard” to the Bishop’s Ranch in memory of his granddaughter Gina, who lost her battle with leukemia at age 15.

1997 Griffin and Joyce received the Healdsburg Museum and Historical Society’s award for historic preservation of an industrial enterprise (Hop Kiln).

1999 Authored Saving the Marin-Sonoma Coast: the Battles for Audubon Canyon Ranch, Point Reyes, and California’s Russian River. Received UCB School of Public Health Hero Award.

2004 Sold Hop Kiln winery.

2010 Audubon Canyon Ranch Board of Directors formally renamed the 1,000-acre preserve on Bolinas Lagoon the Martin Griffin Preserve.

2012 Worked to protect Drake’s Estero as wilderness and lobbied for closure of commercial oyster operations in the estero.

2013 Appeared in Rebels with a Cause, a documentary film on the history of the effort to save Marin County land from development.

2020 Continues his lifelong mission, now lobbying for termination of commercial ranching operations in Point Reyes National Seashore.

How to Help

For more ways to support local businesses, go here.

For more on Marin:

- Keep the Olympic Spirit Going in Marin: Join the Marin Magazine Decathlon

- Fighting for Change: How Marin Organized a Protest In Support of Black Lives Matter in Only 4 Days

- Ultimate Guide to Grilling: Tools and Tips for the Best Backyard Eats

Anne-Christine Strugnell has been a writer for her entire professional life. After growing up in the Boston area and living for six years in England, she discovered Marin—and it was love at first sight. For the past two decades she supported herself and her family as a freelancer for hi-tech firms while also publishing personal essays in MORE Magazine, Self, the Christian Science Monitor, and the Cup of Comfort series. In 2019, awareness of the climate crisis drove her to quit her day job to focus on volunteer work with Resilient Neighborhoods and the Climate Center.

Anne-Christine Strugnell has been a writer for her entire professional life. After growing up in the Boston area and living for six years in England, she discovered Marin—and it was love at first sight. For the past two decades she supported herself and her family as a freelancer for hi-tech firms while also publishing personal essays in MORE Magazine, Self, the Christian Science Monitor, and the Cup of Comfort series. In 2019, awareness of the climate crisis drove her to quit her day job to focus on volunteer work with Resilient Neighborhoods and the Climate Center.