IN MAY OF this year, a Marin storefront shut its doors and quietly marked the end of an era. Marin Holistic Solutions was the last medical marijuana dispensary left in a county whose voters supported Proposition 215, the landmark 1996 state law that legalized marijuana for medical use, by a ratio of 3 to 1.

In the 18 years since Prop. 215 was passed, despite federal laws that still consider it illegal, 32 more states and the District of Columbia have legalized medical marijuana in some form. Another two, Colorado and Washington, lifted prohibition entirely in 2014. (Next month, Alaska and Oregon will also put full legalization before voters.) National polls show support for legalizing medical marijuana at 81 percent and for recreational use at 46 percent.

But California, in many respects the nation’s most progressive state, remains oddly stuck in limbo. In 2010, a more general legalization measure, Proposition 19, fell a few percentage points short of passing, and subsequent efforts for 2012 and 2014 failed due to infighting, funding shortages and logistical challenges. (Some, however, would argue that because medical marijuana identification cards are easy to get in California, the current law functions as a cover for legalized recreational use for people willing to play by the rules.)

Meanwhile, Marin, one of the state’s most liberal counties, has essentially reverted to a pre–Prop. 215 environment, even though, taking into account national trends, an even greater percentage of Marin voters likely now support legalizing medical marijuana than in 1996.

“You have 80 percent of Marin in favor of medical marijuana, but no one wants it in his or her backyard,” says Scot Candell, a San Rafael–based attorney who has represented more than 100 dispensaries in Northern California, including some in Marin. “Everybody votes for it, but then the city councils pass bans.”

Since 2008, when as many as eight dispensaries operated in the county, many of Marin’s 11 cities and towns — including Corte Madera — have forced out existing dispensaries and enacted moratoriums. In others, an apprehensive or fearful stance toward medical marijuana storefronts and the recent federal crackdown on some Bay Area operations, including Fairfax’s Marin Alliance for Medical Marijuana, has kept landlords from hosting tenants that would otherwise be legal under state and local law.

“One of our concerns about medical marijuana for young people is that it legitimizes it, and it makes it more accessible,” says Bob Ravasio, Corte Madera councilman and Twin Cities Coalition for Healthy Youth co-chair. “I totally agree with the therapeutic uses of marijuana, but I don’t think the dispensary system is how it should be distributed. I think it should be treated like a prescription drug and sold through drugstores.”

Meanwhile, the Marin County Board of Supervisors, which has direct jurisdiction over unincorporated areas of the county, has stayed silent. Until now. After years of playing a cautious game of wait-and-see, including ignoring the findings of an August 2013 grand jury that scolded the county for failing to ensure safe access to medical marijuana, the supervisors have decided to act.

Earlier this year, with the closure of Marin Holistic Solutions looming on the horizon, they announced a plan to develop a new set of rules for permitting dispensaries in unincorporated parts of the county. A public workshop was scheduled, and a final draft should be in place by the end of the year, according to District 1 board aide Susannah Clark.

“At least three members of the board are very concerned that we have no legal safe access to medicine in Marin County,” Clark says. “They’re committed to seeing it come before the board this year.”

Supervisor Susan Adams, whose term ends next month, is one of them. Like Clark, she serves on the board’s medical marijuanasubcommittee. After watching a former colleague benefit from cannabis while battling pancreatic cancer, she took a personal interest in ensuring safe access to the drug, she says. Still, she believes, the county’s hesitant and somewhat reactionary stance has been justified.

“This is an issue that has been extremely challenging for local governments, because the state has pretty much been MIA in terms of offering guidance,” Adams says. “We run the risk of losing our federal dollars if we have permissive legislation that allows [dispensaries] to operate.”

That’s why Marin is now studying recent, more permissive ordinances in San Francisco, Santa Cruz and Sebastopol that thus far haven’t led those cities into conflict with the federal government. In fact, she says, the cities have proven they can actively cooperate with the feds on the issue. Now Marin is hoping to follow their lead, Adams says.

Current guidelines for unincorporated parts of the county are based on state regulations: no dispensaries are permitted within 600 feet of schools, and dispensaries must operate as nonprofits. Beyond that, approval is up to landlords’ discretion. Yet without the county’s stamp of approval, no landlords currently appear to be willing to house one.

This situation leaves potentially thousands of local patients — advocacy group California NORML (National Organization for the Reform of Marijuana Laws) estimates the state’s medical cannabis patient population to be as high as 1.14 million people, or about 3 percent of the total — to drive an hour or two round-trip to neighboring counties to visit a dispensary. Others avail themselves of the services of a small handful of unregulated operations that deliver marijuana directly to users’ doors, though some patients and advocates consider this a less safe option that is better suited to less ill, more experienced users who know what they want and have less specific needs.

“We deal with gravely ill, homebound, chronically ill patients every day who don’t want to deal with delivery,” says Corinne Malanca, who in 2011 launched the Greenbrae-based medical marijuana resource United Patients Group after cannabis helped her father survive a bout with cancer. “You just don’t know what you’re getting until they’re at your door. … Every single one of our clientele is severely affected by not having access here in Marin.”

Brian Bjork agrees the county needs storefront dispensaries, even though he directs one of the county’s busiest medical marijuana delivery services. Marin Gardens is one of five or so such services based in Marin (although others based outside county lines may also reach local residents), and Bjork says its employees frequently field calls from new patients hoping to visit in person. That’s been particularly true since May, when Marin Holistic Solutions shut its doors.

“I think a lot of patients would like the convenience of being able to see the medicine and to be able to interact and ask questions,” he says. “There’s only so much you can do over the phone. You can describe it as best you can, but still they’d like to see it. And also some people don’t feel comfortable asking too many questions over the phone.”

Marin Gardens has been on the search for a storefront for three years, Bjork says, but has yet to find a willing landlord. He hopes that action by the Board of Supervisors will encourage landlords and Marin’s other municipalities to ease their resistant stance.

Marin County District Attorney Edward Berberian says that if this happens, he will respect state law and only take up a case against a dispensary if it targets or endangers juveniles, abuses public resources or becomes associated with firearms.

Board aide Clark suggests that in order to ensure ease of access, ideal locations for new dispensaries on unincorporated lands in Marin would be along the Highway 101 corridor and Sir Francis Drake Boulevard in West Marin’s San Geronimo Valley. But it’s too early to tell how many would be permitted or what the final rules might look like, she says.

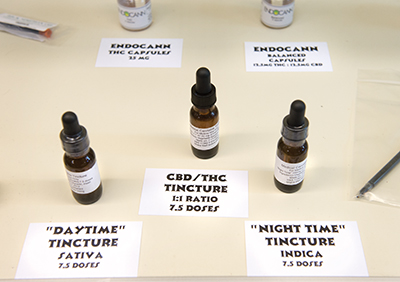

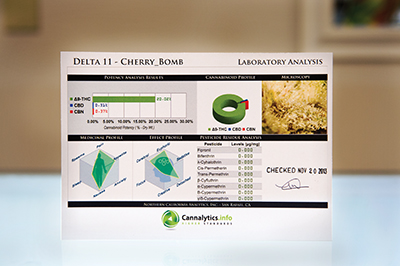

Marijuana analaysis at Delta Delivery.

Alex, who didn’t want his last name used, has been CEO of San Rafael–based Delta Delivery, another of the county’s nonprofit delivery services, for almost three years. With 17 full-time employees, Delta by Alex’s estimate serves about 5 percent of Marin County’s medical marijuana patients. He too laments the county’s current lack of dispensaries. Without a storefront, it can be difficult to serve newer patients or those seeking treatment advice, he says.

“A lot of people who have never used cannabis in their entire lives, and they’re in their 50s or 60s and they get cancer, their doctor prescribes cannabis and they don’t know what to do from there,” he says. “If someone calls who’s just been diagnosed with cancer, which happens quite a lot, I’ll meet with such people in person and try to find what’s going to be best for them.”

Like Bjork at Marin Gardens, he’s hopeful the Board of Supervisors’ pending plan will yield positive results for patients. “Sooner rather than later we’ll start seeing dispensaries in Marin County, and we’ll open a storefront as soon as we can get a permit,” he says. “I’ve got to applaud the supervisors for getting around to agreeing that we need access for Marin County.”

Partly in anticipation of improved (or, essentially, renewed) access to medical marijuana in the county, attorney Candell launched a website earlier this year designed to educate newbies, and perhaps skeptics, on visiting or opening dispensaries, buying or growing specific strains of cannabis, and treating ailments from anorexia to arthritis. In 12 online classes — streaming videos that range in length from 20 to 90 minutes and are available for free at cannabismatters.com — a host of medical marijuana experts, all doctors, expound on various therapeutic uses for cannabis as well as the underlying science. Cannabis is currently prescribed to treat more than 50 different ailments, including AIDS, chronic pain, spasticity, glaucoma, migraines, epilepsy, bipolar disorder and multiple sclerosis.

“As this is becoming mainstream, there are people who haven’t been involved in this industry or didn’t really understand it who are now getting interested,” Candell says. “What we found was lacking was an educational resource for people who are interested in learning about it from a patient’s perspective, for people who are interested in growing their own medicine and for people who are interested in doing their own dispensary.”

Candell himself teaches a few of the online classes, including “Medical Marijuana for New Patients,” intended for people who have a health condition that may be helped by marijuana but who have never used the drug, don’t know where to find it or how to use it, and may be worried about getting into trouble. Featuring nothing more than a straight talking Candell before a black backdrop, the 25-minute video is basic and pragmatic in approach.

Others are a bit more advanced, like Sher Ali Butt’s 40-minute “Lab Testing and Analysis for Cannabis,” full of complex chemistry and scientific language. A biochemist by training, Butt spent two years at Oakland’s cannabis research facility Steep Hill Lab, processing 500 to 600 marijuana samples a day. Suffice to say it wasn’t your stereotypical stoner he had in mind when discussing cannabinoids and chromatography.

Another class, “Advanced Medical Cannabis,” is taught by Dr. Jeffrey Hergenrather of Sonoma County, chair of the national Society of Cannabis Clinicians, wearing a shirt and tie and shoulder-length ponytail. “A lot of people have been involved in this science for many years,” he says in an interview, “and I think we are collectively able to tell the story and shed some light on the utility of cannabinoids and cannabis in the management and treatment of many different diseases.” All without any tie-dye in sight.

Indeed, some of the tension over medical marijuana in Marin likely does stem from the legacy of recreational use and back-to-the-land counterculture of the 1960s. But before the hippies, and even before marijuana was made illegal by the Marijuana Tax Act of 1937, doctors were prescribing cannabis. In fact, the American Medical Association opposed the 1937 act. “How far it may serve to deprive the public of the benefits of a drug that on further research may prove to be of substantial value, it is impossible to foresee,” the organization asserted in a letter to Congress.

Nearly eight decades later, the issue remains unresolved. Nowhere is that more true than in California, and certainly in Marin, where voters helped launch a national movement to legalize medical marijuana in 1996 but in many cases still lack reliably safe access to it.

That’s motivation enough for Dale Gieringer, director of the marijuana advocacy organization California NORML, which ultimately aims to repeal prohibition altogether. “There absolutely has to be an ability to access marijuana for every medical marijuana patient in California,” he says, “no matter where they are.”