In 2018, the days of impulsively swinging by Muir Woods officially ended with implementation of a reserved-parking system. But while visiting that particular wonder requires planning in advance, there’s a more spontaneously accessible—and, arguably, equally beautiful—alternative just 25 miles away.

In many ways Samuel P. Taylor State Park is a living history of Marin County. While it officially opened in 1946, people have been coming to “Camp Taylor” for over a century. Before then, the indigenous Coast Miwok lived here, with a legacy dating back at least 3,000 years.

Today Samuel P. Taylor State Park welcomes nearly 150,000 visitors a year. Some come to stay at the campground, others to picnic in the redwoods or to hike and view wildlife: depending on the season, you can spot everything from gray foxes to owls to coho salmon here.

“It’s a really incredible place,” says Bree Hardcastle, an environmental scientist with the California State Parks Department. “It’s a really unique, natural environment within the Bay Area.”

After a fire broke out at the park last September, Hardcastle served as the department’s resource adviser. Thanks to fortunate weather and hard work, any destruction from the blaze — officially known as the Irving Fire — was ultimately minimal.

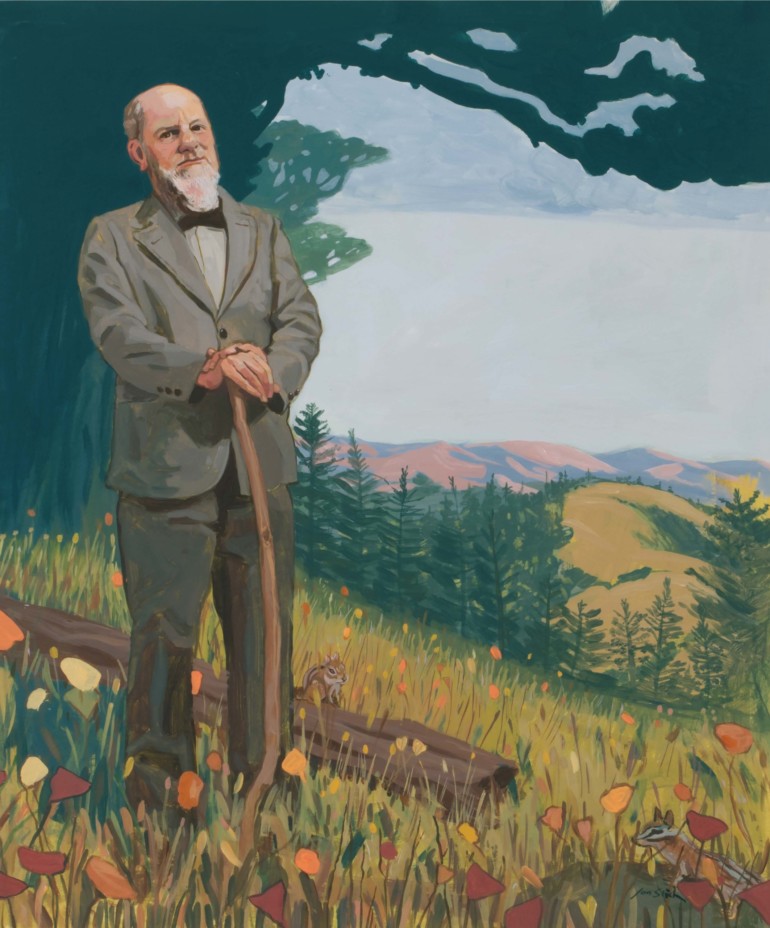

Taylor’s second paper mill as seen in 1889.

“None of our structures were involved in the fire,” she confirms. “It was really just the wildland areas where that fire burned, and they’re all adapted for natural fires. Already the area is rebounding in the way we anticipated, with lots of plants germinating.” In fact, Hardcastle is actually excited to see if the areas affected by the fire will yield species of flora that often grow in the wake of flames.

It won’t be the first time Samuel P. Taylor has faced jeopardy only to rise from the ashes. In 2011, the area was among 70 parks in California slated for closure due to state budget cuts. Fortunately, the National Park Service stepped in with funds to offset expenses, ensuring the park’s survival and, in Hardcastle’s view, actually strengthening its long-term prospects.

“Even though that was a really difficult and challenging time,” she says, “what came out of it was actually pretty amazing. While it was terrible, there have been some positive developments.”

In fact, the full story of Samuel P. Taylor State Park — one of California’s first recreational camping sites and a pivotal place of industry during Marin County’s earliest years — dates to the Gold Rush days. In 1849, it was the tantalizing prospect of riches that compelled the entrepreneurial Samuel Penfield Taylor to sail from his home in New York for San Francisco Bay. After a few successful years of panning for gold and a stint running a lumberyard, he purchased 100 acres of land where the park sits today and followed in his father’s footsteps by building a paper mill in 1856. The Pioneer Paper Mill Company was the first of its kind on the West Coast, and brisk business spawned a community that became the town of Taylorville.

Despite being the namesake for one of Marin’s most gorgeous expanses of nature, Taylor was hardly an environmentalist. As San Anselmo historian Judy Coy notes in a comprehensive biography of him, a dam built by S.P. Taylor & Co. on Daniels Creek led a jury to find Taylor guilty of failing to install a fishway. In 1882 he was fined $50.39, but apparently continued to let his operations obstruct fish from traveling upstream. It wasn’t until 1888, two years after his death, that the Marin Journal mentioned installation of a “first class fish ladder” at Taylorville Dam. Taylor was also suspected of dumping chemicals and refuse into the creek; a lawsuit was filed, but a judge ruled in Taylor’s favor.

Coy’s research yields other fascinating details about Taylor’s life. For one, he was not, as some have suggested, a descendant of George Taylor, the Pennsylvania politician best known as a signer of the Declaration of Independence. And Taylor’s wife, Sarah Washington Irving Taylor, most likely had no blood relation to the famed Legend of Sleepy Hollow author for whom she may have been named.

In fact, it was questions about the latter that first inspired Coy to dig deeper: “I’m the chair of the San Anselmo Historical Commission. One day, I was working as a docent at our little museum and someone came in asking about Sarah. The relation that’s always been assumed is that she was descended from the famous writer, and this woman came in and was questioning that. I’ve always been interested in genealogy, and so I started to look into it.”

Together, Coy and co-author George H. Stevens discovered a wealth of knowledge on the lineage of both Taylor and Sarah Irving, creating an impressively full picture of the lives of two renowned Marin pioneers.

At its peak, Taylor’s paper mill provided newsprint for local publications like the Daily Alta California, the San Francisco Morning Call and the Daily Evening Bulletin. His business operations later helped ensure that the North Pacific Coast Railroad had a line running west to Tomales Bay, and at various points in his life he owned a broom factory in San Francisco and served on the board of directors of the Mechanics Institute.

The Azalia Hotel, part of Camp Taylor Resort, circa 1908.

The proximity of Taylor’s land to San Francisco — along with its staggering beauty and nature amenities — compelled a number of city dwellers to venture out for respites from urban living. In 1878, the Bohemian Club held its inaugural outdoor “jinks” there, while a Daily Evening Bulletin ad from 1879 calls Camp Taylor “the most beautiful resort in the state.”

Many of Taylor’s children lived in Marin, and four of their residences are still standing today, Coy notes. “They’re in good shape. I do a walking tour of the Seminary area and three of them are there, so I always talk about them.”

While Marinites historically have gone to great lengths to protect local parks, one way we can help preserve Samuel P. Taylor for future generations, Hardcastle says, is simply go there — help kids discover the magic of watching a salmon spawn or the joy of eating a sandwich beside a gurgling creek.

“It takes all of us actually caring about what’s there to have the desire to protect it,” she adds. “By visiting, engaging family members and helping young people develop a love for the park, we expand the number of people who care about its stewardship. That’s critically important for its long-term sustainability.”

These days Hardcastle is eager to share findings from the first three years of the Wildlife Picture Index Project, in which cameras placed around the park may teach and better inform department officials about the diverse wildlife there. “The cameras have detected some rare critters,” she enthuses.

While those creatures are locally uncommon, it’s perhaps not terribly surprising they’ve found this special setting and decided to stay. Such is the allure of Samuel P. Taylor, a small slice of paradise in the middle of Marin County’s other natural treasures.

This article originally appeared in Marin Magazine's print edition with the headline: "A Golden Resource".